A Brief History of Creation (5 page)

Read A Brief History of Creation Online

Authors: Bill Mesler

In a world of European science dominated by Greek and Roman classical thinking, Redi was a new breed of natural philosopher. He was, in his younger years at least, skeptical of everything. Books were useful sources of facts. Knowledge was to be accumulated. But everything should be put to the test, from miraculous wards against poison to even the revered Aristotle's theories on the spontaneous generation of life.

I

N THE TENTH CENTURY AD

, the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII commissioned a compendium of practical agricultural wisdom. Called the

Geoponica

, it became a sort of farmer's almanac for Europeans over the next six centuries. It was filled with useful knowledge like instructions for making wine or tips on breeding cattle. There was a lot about managing bees, something essential to productive agriculture. It even included a recipe for creating bees:

Build a house, ten cubits high, with all the sides of equal dimensions, with one door, and four windows, one on each side; put an ox into it, thirty months old, very fat and fleshy; let a number of young men kill him by beating him violently with clubs, so as to mangle both flesh and bones, but taking care not to shed any blood; let all the orifices, mouth, eyes, nose etc. be stopped up with clean and fine linen, impregnated with pitch; let a quantity of thyme be strewed under the reclining animal, and then let windows and doors be closed and covered with a thick coating of clay, to prevent the access of air or wind. Three weeks later let the house be opened, and let light and fresh air get access to it, except from the side from which the wind blows strongest. After eleven days you will find the house full of bees, hanging together in clusters, and nothing left of the ox but horns, bones and hair.

It read like a magical spell, but even as late as the Renaissance, it was still considered science. After all, it worked. The bee recipe had been around at least as long the Roman poet Virgil. There were multitudes of similar recipes covering all manner of creatures. They could even be found in the works of one of the greatest Renaissance scientists, the Flemish physician Johannes van Helmont.

Historians have long grappled with the term “Renaissance science” because the science of the period had two very distinct phases. The first was restorative, as men of learning sought to reinstate the work of Greek thinkers like Aristotle and Anaximander, which had been largely lost and forgotten to western Europe during the Middle Ages. The second phase was innovative, as they began thinking of new, original theories, and using the process of experiment to test these ideas themselves. Van Helmont had a foot in both phases of the Renaissance.

A native of Brussels, then part of the Spanish Netherlands, van Helmont had spent his formative years at university in Leuven. There, he had enthusiastically thrown himself into the works of Galen and Hippocrates, the great figures of classical physiology. But as his studies progressed, he began to become disenchanted with the classics, finding them empty and

unconvincing. Many years later, he would write that while he once found such works “certain and incontrovertible,” he eventually felt his years of study “were worthless.” He gave away all the books he had acquired as a student. His one regret, he would often tell people, was that he had not burned them.

Van Helmont went on to become one of the most important natural philosophers of the early Renaissance. He made remarkable strides in the understanding of gases, becoming the first person to isolate carbon dioxide, which he called “gas sylvestre.” It was he, in fact, who coined the term “gas.”

As an experimentalist, van Helmont had few peers. Even fewer shared his commitment. He spent five years conducting his most famous experiment, carefully monitoring and recording the growth of a tree to prove his hypothesis that plants gain weight from water and air, not from soil as people had always believed. Thus he laid the groundwork for a future understanding of photosynthesis. He also delved into the nature of body fluids, which he called “ferments,” such as stomach acids and semen. He connected them to the chemical reactions that caused changes in the body. This was a monumentalâthough underappreciatedâstep in humankind's understanding of how living things work. It anticipated the modern theory of enzymes, the large organic molecules that control all the chemical processes that sustain life. By the nineteenth century, many scientists would come to see these processes as the key element in what makes living things living.

Yet van Helmont's place in the pantheon of science was often contradictory. Even as he challenged the assumptions of the classics in order to forge his own conclusions, van Helmont remained obsessed with ancient mysticism and alchemy, including some of the most questionable ideas derived from Greek science. Van Helmont did not shy away from using the term “magic,” which he embraced despite his deep Roman Catholic faith. He was fascinated by Aristotle's ideas about spontaneous generation and was considered one of the periods foremost authorities on the subject. He even created recipes for bringing various living creatures to life. His most famous was a recipe for creating mice. It involved mixing

a sweaty shirt with grain in a barrel and waiting for the wheat to “transchangeth into mice.”

Francesco Redi found van Helmont's recipes about as credible as the stones brought by the Franciscans, as he did all such recipes based on spontaneous generation. He decided to put the theory to the test. He chose to focus on the fly. As anyone could plainly see, flies were not born in a conventional sense; they simply emerged from all manner of filth. People could say with absolute certainty that there was no such thing as a fly egg for the simple reason that nobody had ever seen one. But Redi had an epiphany when reading an account of spontaneous generation found in Homer's

Iliad

. “What if it should turn out,” he later recounted, “that all the grubs that you find in flesh are derived of the seeds of flies and not through the rotting flesh itself?”

During July, the time of year when flies seemed to be at their most numerous, Redi placed a snake, a fish, some small eels, and a piece of raw veal into four different flasks, tightly enclosing each after they had been filled. He then did the same thing with four more flasks. These, though, he left open, exposed to the air and any insects that might happen by. Just as Redi expected might happen, maggots appeared on the rotting flesh in the open containers, but not in those he had shut off from the air.

The results supported Redi's hypothesis, but he realized the experiment was not definitive. Anticipating his critics, he wondered whether the maggots failed to appear in the sealed jars because they needed air to survive. So he devised an even more ingenious experiment, using containers wrapped in gauze instead of sealed containers. Maggots did appear, but only on the outside of the gauze. For Redi, the only viable explanation was that flies had been drawn to the decaying meat, but, unable to penetrate the gauze, had laid their eggs on its surface.

School textbooks would one day remember it as the “Redi experiment.” What made it such a seminal event in the history of science was not so much what Redi had proved or disproved. It was, rather,

how

he had done it: by developing a hypothesis and creating two very different sets of experimental conditions to test his theory. It was one of the earliest and finest examples of a controlled scientific experiment.

Provando e riprovando

.

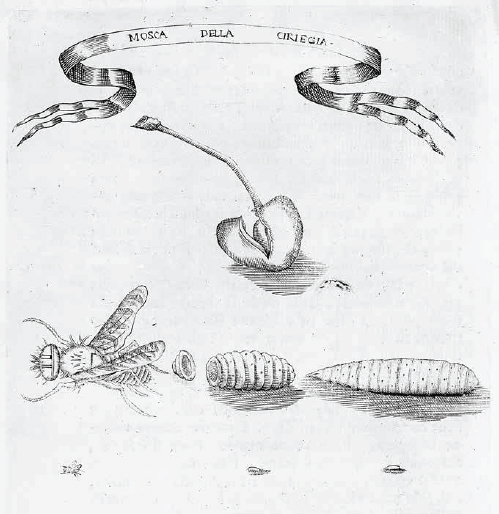

The life cycle of the fly, from

Experiments on the Generation of Insects

.

Soon, Redi was undertaking similar experiments with all kinds of insects. These formed the basis of his greatest work of science,

Experiments on the Generation of Insects

âfor its time a masterpiece of careful observation and experiment. In it, Redi claimed to have disproved not only Aristotle's theory of spontaneous generation, but the very belief that nature, free of the hand of God, could have given rise to life. An artful writer, Redi summarized poetically the beliefs held by the classical Greek philosophers who thought that nature alone had given birth to life:

Many have believed that this beautiful part of the universe which we commonly call the Earth, on leaving the hands of the Eternal, began to clothe itself in a kind of green down, which gradually increasing in perfection and vigor, by the light of the sun and nourishment of the soil, became plants and trees, which afforded food to the animals that the earth subsequently produced of all kinds, from the elephant to the most minute and invisible animalcule.

To Redi, such a vision was incompatible with nature's laws. Echoing the words of the Dutch naturalist Jan Swammerdam, he wrote, “All life comes from an egg.”

R

EDI'S CAREER IN THE SCIENCES

would prove to be relatively short-lived. In May of 1670, Grand Duke Ferdinando II fell ill. The official cause was “apoplexy,” a word then often used to describe what we would now call a stroke. Physicians attended him with the most sophisticated treatments they had at their disposal, applying hot irons to his forehead and smothering him with the flesh of dead pigeons. The treatments worked about as well as the stones said to ward against poison that the grand duke had once been given by the Franciscans. He died two days later.

The duke's only son, Cosimo III, assumed the throne. His father had wanted to give Cosimo a modern scientific education, but the duchess Vittoria would have nothing of it. The new grand duke was his mother's child in nearly every way. It was said that he never in his entire life smiledâa fact that his admirers took as a sign of his great religious devotion. His reign became remembered mostly for its oppressive laws against the city's Jewish population, which had grown to Italy's largest under his father's benevolent rule. He was also obsessed with chastity, establishing laws against making love near windows or doors, and even against women admitting young men who were not relatives into their houses. Homosexuals were beheaded. A biographer would later describe Cosimo as “a devotee to the point of bigotry; intolerant of all free

thought; hated by his wife; his existence a round of visits to churches and convents.”

Redi found his official position at court unchanged. He had long played the role of intermediary between Cosimo III and his father during their disputes, which were constant, and the new grand duke held Redi in some esteem. But Redi's career of scientific inquiry was no longer a viable option, and the younger Cosimo shuttered the Accademia del Cimento.

Redi instead threw himself into a new academy devoted to Tuscan literature, the Accademia della Crusca. He helped write the first Tuscan dictionary and authored several epic poems. He became far more famous, in his time, for his poetry than his science. His greatest work,

Bacco in Toscana

, is still considered a masterpiece of Italian literature. It revolved around a man's struggle to supplant the Roman god of wine. “So daring has that bold blasphemer grown, he now pretends to usurp my throne,” laments the vengeful god Bacchus in Redi's epic poem.

Toward the end of his life, Redi's health began to fail from epilepsy. According to some accounts, he embraced Catholic mysticism, spending his days bathing in holy oil and spent a fortune on ribbons rubbed on the bones of Saint Ranieri, said to have miraculous healing powers. His own descriptions of his conditions seemed to imply that they were the result of nervous hypochondria.

Though Redi's great scientific work,

Experiments on the Generation of Insects

, was widely read, its true significance would have been lost to most people of the era. Redi had employed the tool of experimentation to ask whether life could truly come from nonlife. To him, it could not. And he was confident that he had proved the “fact” with an incontrovertible experiment. Yet few accepted that he had settled the question of spontaneous generation, because nobody could say definitively that they had seen a fly's egg.

Doubt often wants to grow at the foundation of truth

.

But meanwhile, far to the north, in Holland, an obscure Dutch haberdasher had acquired a copy of

Experiments on the Generation of Insects

. He was quite sure that what Redi was saying was correct, and not just because he believed in the infallibility of Redi's experimental methodology. He was quite sure because he had actually seen the egg.