A Brief History of Creation (7 page)

Read A Brief History of Creation Online

Authors: Bill Mesler

By van Leeuwenhoek's time, lens making was all the rage in Holland, and even Baruch Spinoza earned his living as a lens grinder. The most valuable lenses were used to make telescopes, since they could be used to navigate at sea and had important military applications. But there was a market for lenses that could see small things as well, particularly for those, like van Leeuwenhoek, in the textile trade. These were little more than what would later be known as magnifying glasses, but they could be used to accurately gauge the quality of cloth, and to closely examine the technique and skill of needlework.

In 1665, interest in microscopy was kindled by the publication of a marvelous book entitled

Micrographia

. Its author was an Englishman by the name of Robert Hooke, assistant to the famous Irish chemist and

inventor Robert Boyle. As well as being a brilliant investigator of the natural world, Hooke was a gifted artist, and the book was filled with fabulous illustrations. These gave

Micrographia

a wide appeal, far beyond the narrow audience of those interested in a complex book of natural philosophy. Many of his subjects were mundane objects, but to a reader in the seventeenth century, the view from the lens of Hooke's microscope turned them into objects fantastic and magical.

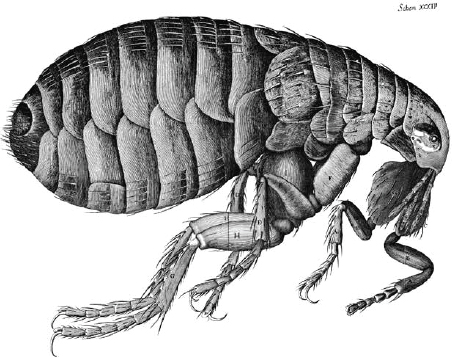

Hooke's observations began with simple manufactured objects. Several were things a draper like van Leeuwenhoek might have chosen to observe. There were studies of the head of a needle and a piece of linen. Eventually, the book worked its way to more complex subjects, and Hooke turned his looking glass to plants, both commonplace plants like rosemary and exotic ones, like a plant brought from the East Indies called cow-itch. Finally came Hooke's most amazing and complex examinations, those of animals. He included everything from hair and fur and feathers to parts of insects

and other small organisms, like the eyes of the gray drone fly or the teeth of a snail.

Hooke's drawing of a flea in

Micrographia

.

One of the first illustrations in Hooke's

Micrographia

was a drawing of his microscope. It looked remarkably similar to an archetypical microscope design still used four centuries later, like a spyglass turned to the ground, with a small metal thimble upon which to place one's eye. Hooke included exhaustive instructions on how he constructed his microscope, even the methods he used to blow and grind his glass lenses. The instructions were so detailed that they filled much of the first half of the book.

B

Y THE TIME

Micrographia

appeared, van Leeuwenhoek was back in Delft, married and settled in a comfortable house in town. Soon he had built his own microscope based loosely on Hooke's design. It lacked the beauty of Hooke's tubular device, but van Leeuwenhoek was not completely blind to aesthetics. All of its component parts were made of copper or silver. When it came to the lens, van Leeuwenhoek made some changes to Hooke's design. Like all the most powerful microscopes of the time, Hooke's was a compound microscope. It had lenses stacked upon each other, each increasing the magnification of the last. Van Leeuwenhoek's microscope, in contrast, had but a single lens, yet he could see things that required a magnification five or six times greater than Hooke's provided.

Unlike Hooke, Van Leeuwenhoek was secretive about the methods he used to construct his lenses. He vowed never to share or even discuss them, and he never did, even when his secrecy threatened his own credibility. One modern observer, the artist David Hockney, has speculated that he used special techniques to increase the clarity of what he could see, including manipulating lighting or the background of his specimens. These could have been the same tricks used by many of the great Dutch painters of the period, who were masters of lighting and perspective. Hockney would also speculate that van Leeuwenhoek had been aided by something called a

camera obscura

âa simple box that, using light and mirrors, could project an unusually clear image that was much larger than the original,

almost like a slide projector. Its design would eventually be used by the Lumière brothers, Auguste and Louis, as the basis of the first motion picture projector.

At least part of the reason van Leeuwenhoek's microscopes were so effective was that they were based on a

single

-lens design. The biggest problem with the compound microscopes of men like Hooke was that each additional lens obscured the clarity of what the observer could actually seeâa phenomenon known as chromatic aberration. Van Leeuwenhoek's microscopes, which relied on one extremely powerful lens, didn't have that problem.

Van Leeuwenhoek was able to see things that no other human being on Earth had ever seen. He first turned his attention to the same mundane objects he found in Hooke's book, but saw details that Hooke had missed on the stingers and mouths of bees, and even in their eyes. He shared these discoveries with a few of his acquaintances, including Regnier de Graaf, a natural philosopher, accomplished physician, and inventor of one of the early prototypes of the hypodermic needle. De Graaf soon put van Leeuwenhoek in touch with Henry Oldenburg, an important natural philosopher in London. In the years to follow, van Leeuwenhoek would gain a reputation as the finest microscopist in the world. Oldenburg was the one who would make sure the rest of the world saw what van Leeuwenhoek had accomplished.

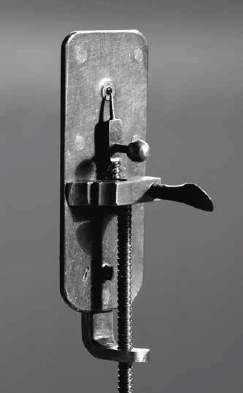

One of van Leeuwenhoek's microscopes.

Â

A

GERMAN FROM BREMEN

, Henry Oldenburg's real name was Heinrich Oldenberg. He had first come to England as a diplomat but became a lifelong resident after marrying the daughter of an influential clergyman. He had a passion for the sciences. He was an early member of a small group of natural philosophers who met informally at London's Gresham College. They eventually adopted the name of the Philosophical Society of Oxford. In 1662, probably in response to the French court's support of a rival group of natural philosophers called the Montmor Academy, the Oxford group received a royal charter from King Charles II and became the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge. Better known as simply the Royal Society, it rapidly became the best-known scientific body in the world, a distinction it would hold until the twentieth century.

The mathematician William Brouncker became its first president, and Robert Hooke was appointed curator of experiments. Oldenburg became the first secretary, but that appointment would be short-lived. In 1667, Oldenburg was arrested by British authorities and locked away in the Tower of London, suspected of espionage on the basis of a letter he had written to a friend in France, a fellow natural philosopher, in which he related events in the city. It had been a time of great xenophobia in London. A Dutch fleet was threatening England with invasion, and for the first time in their lives, Londoners could hear the guns of foreign ships off their shores. The city was also undergoing a severe outbreak of the bubonic plague, the last such outbreak in its history. Over the previous two years, the disease had claimed a hundred thousand lives. To make matters worse, a huge fire had burned down nearly 80 percent of the city the previous year. The process of rebuilding was under way, under the auspices of a brilliant young architect named Christopher Wren, another of the Enlightenment luminaries who happened to be born in 1632.

Oldenburg was released after the threat of Dutch invasion had passed. He wrote to his old friend Robert Boyle, whose children Oldenburg had once tutored, asking to be reinstated to the Royal Society and promising “faithful service to the nation to the very utmost of my abilities.” Most

welcomed him back, but there was a cloud over him that never quite went away. To many Englishmen, even some of those who knew him from the Royal Society, Oldenburg's loyalties remained in question. In later years, even Robert Hooke, suspicious of everyone and a staunch nationalist, questioned whether Oldenburg wasn't secretly in league with the French.

Yet Oldenburg became the organizational glue that enabled the Royal Society to establish itself as the world's premier repository of scientific thinking. His prolific correspondence with naturalists around the world made him a human nexus of Enlightenment knowledge. But the huge volume of letters he received from abroad also worried him. His arrest had made him cautious. He began asking his correspondents to address their letters to a “Mr. Grubendol,” an anagram for “Oldenburg.”

M

ICROGRAPHIA

was the first major work published by the Royal Society. Originally, the project was to be completed by Christopher Wren, who was almost as accomplished a scientist as he was an architect. Citing a lack of time, he had passed the book on to Hooke. With funding from the Crown, the Royal Society also began publishing a periodical. Oldenburg became its first editor, and it didn't take long for the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society to establish itself as the world's scientific paper of record, a position it occupied for the next two hundred years.

Many of the

Philosophical Transactions

' early issues were devoted to microscopy. In 1673, the journal included a letter from Regnier de Graaf, the physician from Delft, who told of a “certain most ingenious person here named Leeuwenhoek” who had “devised microscopes which far surpass those we have hitherto seen.” The claim was greeted skeptically. Nobody had ever heard of van Leeuwenhoek. An inquiry was made to the Dutch statesman and poet Constantijn Huygens, whose son Christiaan would go on to fame as an important mathematician and astronomer. Huygens wrote that van Leeuwenhoek was a man “unlearned both in sciences and languages, but of his own nature exceedingly curious and industrious.”

At de Graaf's urging, van Leeuwenhoek dispatched his first letter to Oldenburg. It had all the charming reluctance and frankness that characterized

his future correspondence. “I have no style, or, pen, wherewith to express my thoughts properly,” he wrote. “Besides myself, in our town there be no philosophers who practice this art.” He added a telling fact about his nature, one that he would never escape through all his future fame and success: “I do not gladly suffer contradiction or censure from others.”

The letter included some observations of the stingers of bees and of lice, which could only have come from a microscope more powerful than Hooke's. There were also some simple sketches. Van Leeuwenhoek didn't have Hooke's artistic gift and never attempted a serious drawing. Later he had pictures drawn by local artists. Sometimes he showed them a simple sketch he had made upon which to base their own work, but he described these as no more than a few simple lines on paper. As far as anyone knows, he never let the artists simply look through his microscopes. To do so would have diminished his role as translator of the microscopic world, which for many years literally he alone had access to.

Van Leeuwenhoek's first communication was met with skepticism. That he was a mere haberdasher only increased the incredulity. Nonetheless, Oldenburg published an edited version in the

Philosophical Transactions

, adding a mildly sarcastic commentary of his own. Surely, Oldenburg wrote, they hadn't heard the last of this van Leeuwenhoek “who doubtless will proceed in making and imparting more Observations, the better to evince the goodness of these his glasses.” Oldenburg was essentially inviting the Dutchman to prove he could see all that he claimed.

This, van Leeuwenhoek did. Over the next four decades, he dispatched some 560 letters filled with astounding scientific observations to the world's leading institutions and journals of natural philosophy. All of these were written in his colloquial style, meandering through mundane topics even as he made astounding scientific revelations. But van Leeuwenhoek never published a book or even what might generously be called a scientific paper. He probably never adopted a style more suited to publication because he couldn't read the foreign journals in which his work appeared. The only language he ever mastered was Dutch.

Most of van Leeuwenhoek's letters were directed to the Royal Society, and Henry Oldenburg became, to a large extent, his personal translator

and editor. It is ironic that van Leeuwenhoek would owe so much of his initial fame to a German. Van Leeuwenhoek didn't care for Germans, and when speaking of them, he had a habit of turning to one side and exclaiming, “Oh, what a brute!” Until his death in 1677, Oldenburg dutifully edited all of van Leeuwenhoek's communications. Many of these were addressed to “Mr. Grubendol.”