A Brief History of the Anglo-Saxons (3 page)

Read A Brief History of the Anglo-Saxons Online

Authors: Geoffrey Hindley

899 | Alfred, king of the Anglo-Saxons, dies |

903 | King Edward (the Elder) crushes rebellion of Æthelwold |

910 | Battle of Tettenhall: Edward defeats Northumbrian Danes |

918 | Death of Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians. Mercia taken over by Edward, king of the Anglo-Saxons |

924 | Death of Edward, accession of Æthelstan |

925 | Coronation of Æthelstan at Kingston Æthelstan coinage with style ‘REX TOTIUS BRITANNIAE’ Grately Code issued about this time |

934 | Æthelstan makes pilgrimage to shrine of St Cuthbert at Chester-le-Street |

937 | Battle of Brunanburh: Æthelstan’s victory over the Vikings of York and their northern allies |

939 | Death of Æthelstan and accession of Edmund |

943 | Baptism of Olaf, Viking king of Dublin and York, Edmund standing as his sponsor |

946 | Murder of Edmund at Pucklechurch, accession of Eadred |

952–4 | Eadred achieves submission of York Vikings Eric Bloodaxe killed at Battle of Stainmore |

955 | Death of Eadred, accession of Eadwig |

957 | Edgar king in Mercia and Northumbria |

959 | Death of Eadwig, Edgar king of all the English kingdom Dunstan, archbishop of Canterbury |

961 | Oswald becomes bishop of Worcester and, two years later, Æthelwold bishop of Winchester. The three principal figures of tenth-century church reform now in post. |

973 | Edgar’s ‘imperial’ coronation at Bath |

970s | Edgar’s reign sees reforms of Anglo-Saxon coinage with royal mints established nationwide |

c. | Council of Winchester approves the |

975 | Death of Edgar, accession of Edward the Martyr |

978 | Murder of Edward, accession of Æthelred II |

981 | Seven Danish ships sack Southampton: the first incursion since death of King Edgar |

990 | Sigeric, archbishop of Canterbury, travels to Rome for his pallium. A detailed account of his journey survives |

991 | Battle of Maldon: Ealdorman Byrthnoth killed resisting Norse raiders. Archbishop Sigeric advises paying tribute of 10,000 pounds, the first in Æthelred’s reign |

994 | Swein Forkbeard and Olaf Tryggvason of Norway lay siege to London |

995 | Community of St Cuthbert move from Chester-le-Street to Durham |

1002 | Wulfstan becomes archbishop of York and bishop of Worcester. St Bryce’s Day Massacre |

1009 | Arrival of army of Thorkell the Tall |

1012 | First levy of |

1013 | Swein of Denmark invades; Æthelred and his family flee to Normandy |

1014 | Death of Swein |

1015 | Return of Æthelred; Cnut campaigns against Edmund Ironside |

1016 | Death of Æthelred; accessions of Cnut and Edmund, who dies 30 November |

1017 | Cnut marries Queen Emma |

1020 | Cnut’s first letter to the English |

1021 | Thorkell the Tall exiled |

1027 | Cnut’s journey to Rome |

1035 | Death of Cnut; Harold I proclaimed at Oxford |

1040 | Death of Harold I, accession of Harthacnut |

1042 | Accession of Edward the Confessor |

1044 | Robert of Jumièges appointed bishop of London |

1051–2 | Expulsion and return of the Godwine family |

1053 | Reputed visit to England by Duke William of Normandy |

1055 | Tostig Godwineson appointed earl of Northumbria |

1063 | Earls Harold and Tostig campaign successfully against the Welsh |

1065 | Rising in the north against Tostig Harold has King Edward appoint Morcar of Mercia earl of Northumbria |

1066 | January, King Edward dies; Harold crowned king in Westminster Abbey Harald of Norway invades England with Tostig but Harold defeats them at Stamford Bridge, 25 September; William invades, 28 September. William defeats the English army at Hastings, 14 October. |

1068–9 | Northern rebellions against William |

1071 | Rebel force on Isle of Ely surrenders to William; Hereward the Wake makes good his escape |

1075 | Death of Edith, queen of Edward the Confessor, at Winchester. King William has her body brought solemnly to Westminster to be interred beside that of her husband in the abbey |

1085–6 | The Domesday survey |

1087 | Death of William the Conqueror |

1088 | William II, facing rebellion led by Odo of Bayeux, ‘summoned Englishmen and placed his troubles before them [and they] came to the Assistance of their lord the king . . .’ |

1092 | Death of Wulfstan, bishop of Worcester – the last English bishop in post The last consecutive entry in the |

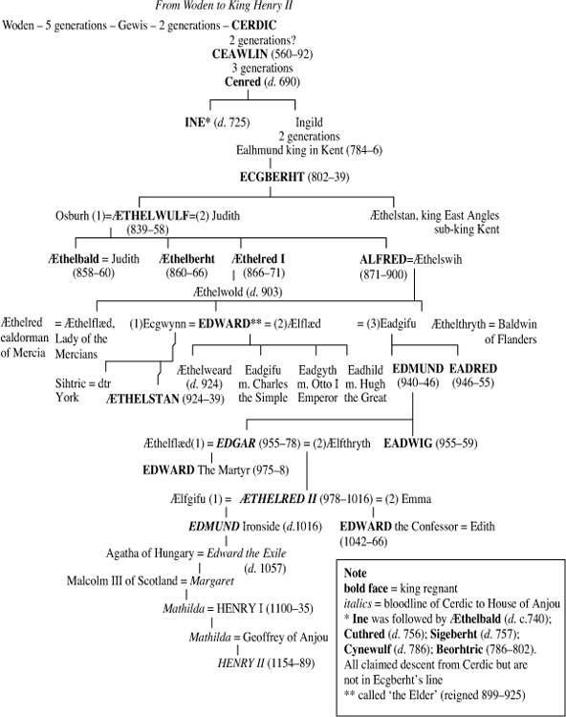

SELECTIVE GENEALOGY OF THE ROYAL HOUSE OF CERDIC/WESSEX/ENGLAND

INTRODUCTION AN IDEA OF EARLY ENGLAND

‘Late Anglo-Saxon England was a nation state.’ So wrote a leading historian some ten years back. The words were controversial then and they are controversial now. Yet Professor Campbell was quite explicit as to his meaning. ‘It was an entity with an effective central authority, uniformly organized institutions, a national language, a national church, defined frontiers . . . and, above all, a strong sense of national identity.’

1

It is, perhaps, hardly a view that squares with the received wisdom outside the world of Anglo-Saxon studies. But England was certainly a nation state at a very early era of European history.

In this book I claim no originality of research, but want to tell the story of the first centuries of the English in Britain and in Europe and show how the historical reality of an English identity grew out of traditions of loyalty and lordship from the epic heritage of a pagan past embodied in the poem of

Beowulf

in a common vernacular language, and how the notion of a warrior church produced an expatriate community that made pioneering contributions to the shaping of the European experience. In the process we should see how, while there was ‘a nation of the English centuries before there was a kingdom of the English’,

2

that kingdom, based on a shared vernacular language and literature, at the time of its overthrow in

1066 had achieved a substantially uniform system of government that, for good or ill, was in advance of any contemporary European polity of a comparable area.

3

It was the culmination of a gradual coming together of separate political entities. As a result, the story comprises overlapping narratives of rival kingships – Kentish, Northumbrian, Mercian and so forth – up to the mid-tenth century, so that the reader will sometimes find the chronology running ahead of itself. Above all, this main account is of necessity interrupted by chapters not set in England at all but on the Continent of Europe, where three generations of expatriate English men and women made formative contributions to the birth of a European identity.

In the early 700s Wynfrith ‘of Crediton’ in Devon, otherwise known as St Boniface, patron saint of Germany, where he worked for most of his life, was in the habit of referring to his home country as ’

transmarina Saxonia

’ (‘Saxony overseas’). He described himself as of the race of the Angles. His younger contemporary, the Langobard churchman Paul the Deacon, noted the unusual garments that ‘

Angli Saxones

were accustomed to wear’ and in the next century Prudentius, bishop of the French city of Troyes, writes of: ‘The island of Britain, the greater part of which Angle Saxons inhabit’ (

Brittaniam insulam, ea quam maxime parte, quam Angli Saxones incolunt

).

4

Wilhelm Levison, the great authority on the English presence on the Continent in the early Middle Ages, actually suggested that the term Anglo-Saxon may have originated on the Continent to distinguish them from the German or ‘Old’ Saxons. However, most scholars now tend to accept that the name of the ‘Angles’ had earlier origins.

We have here a cluster of terms – Germany, Saxony, Langobard, French – that are not what they seem. The geographical identity of the island of Britain is still, give or take a coastline indentation or two, what it was twelve hundred years ago, but ‘France’ was part of the region known as ‘Francia’, the land of the western Franks. Gaul

was the Roman term for the province and the term ‘Neustria’ is sometimes used for territories in southern Francia. The Langobards were a Germanic people who had established a kingdom in northern Italy remembered in the word Lombardy. What today we might call ‘Germany’ then comprised parts of the wesern regions of the modern state, mostly the lands of the East Franks – Francken (Franconia), Hessen, Lothringen, Schwaben (Swabia) and Bayern (Bavaria). The pagan Germanic-speaking tribes of Saxony (those ‘Old’ Saxons) had yet to be brought into the Christian domains of the eastern Franks, though they too were Germans.

This leaves us with the Anglo-Saxons. They were at first a mixed collection of Germanic raiders who had crossed over to the island Britain and would eventually become subsumed under the name of ‘English’. Some may have settled as early as the 370s, following a great incursion of Scotti (from Ireland), Picts (from Scotland) and Saxons described by the Roman writer Ammianus Marcellinus for the year 367. In much the same way, the Germanic tribes on the east bank of the lower Rhine, known collectively as ‘the Franks’, who began to disturb that part of the Roman imperial frontier in the third century, were made up of three main groups: the Salian, the Ripuarian and the Chatti or Hessian Franks. As for the original inhabitants of Britannia, whose descendants still maintain their identity in Wales, they considered the English quite simply as Germans and continued to call them that as late as the eighth century.

5