A Cage of Roots (11 page)

Authors: Matt Griffin

‘Oh, my God!’ she exclaimed. ‘I think I might be sick.’

Then, looking frantically behind her: ‘Is she …?’

‘She’s not coming through, don’t worry. That was close though!’ Taig laughed, and then stopped to inspect the land. He breathed deep, and a tear emerged from one clear-blue eye.

Long tufts of mist hovered low between the shoulders of mountains that stretched to grey lowlands at the horizon. Fat clouds dropped veils of rain here and there

over the green. Dark forests clambered up the foothills, divided by the great glassy river.

‘At last, I am home,’ he said.

‘It’s beautiful,’ Benvy said, still looking at Taig. ‘But where are we?’

‘Welcome to Fal, young Benvy. The young land that will grow up to be your Ireland. I have missed it greatly. It’s been thousands of years after all.’

He lingered a while longer, savouring the damp air, holding his face up to the drizzle, and then picked up both his and Benvy’s bags.

‘Right, let’s find a place to get warm and sleep for the night. Take care on the way down.’

From the small stand of rocks, a thread-like rut snaked down the mountainside. It looked treacherous. Thick tussocks of wiry grass slumped among the boulders, weighed down by heavy dew. There would be very little to hold on to on the way down.

‘In fact, here.’ He crouched with his back to her.

She stared blankly at him.

‘Well? Hop on!’ Taig offered again.

‘What?’ she exclaimed. ‘Eh, no. I’m good, thanks.’

She took a step, and instantly slipped on a loose rock. Taig caught her for a second time, and resumed the crouch.

‘Okay,’ consented Benvy. ‘But we

never

tell anyone of this.’ And she hoisted herself onto his back. He smelled

of wet stone and moss.

‘Off we go,’ he said, and began carefully picking his way along the narrow track.

After a while, the slope began to ease and Benvy was able to walk herself. They stepped through lead-coloured stones and knee-high grass for hours, until they arrived at a riverbank. Cold water surged over a small falls, roaring like a great crowd of people. Daylight was on the wane by the time they reached the outermost trees of a thick and silent evergreen wood. They found a spot with flat rocks and short grass, between a great pine and the bank.

‘This’ll do us, young Benvy,’ announced Taig as he set the bags down. ‘You go and get some kindling wood, will you? Small pieces, nice and dry.’

When Benvy returned, she found Taig had prepared a circle of rocks to fence the fire, and had fetched some bigger logs. When the fire was lit, he showed her how to make the seating more comfortable, using pine needles from the forest floor. Then they opened their packs and ate enthusiastically. When they finished, Taig filled their canteens from the river. It was the sweetest water Benvy had ever tasted.

‘What do we do now then?’ she asked.

‘Well, first, we sleep. I don’t know about you, but all the excitement back there has taken it out of me.’

‘That’s not what I mean. I mean tomorrow; I mean

next

. And who

was

that crazy woman, anyway? You said she was called Deirdre? And how did she do those things? With her eyes, and the storm? It was the most frightening thing I’ve ever seen!’

‘Most things are frightening when it comes to magic, my young friend. That’s why it’s best avoided where possible. And as to who she was? Well, she was a … friend. Once, a long time ago. I knew her, and then we couldn’t be friends any more. It got complicated, and I am not a complicated man. She wanted to stay friends, so she wasn’t too happy when I ended our time together. A lesson learned, young girl: never involve yourself with someone who knows magic.’

‘So there are more of you? Back home, I mean. In our time?’ she asked.

‘Yes, there are a few around, beings who we would call “Old Ones”. They are magic, and they were ancient even when we were young. I think they’ve been around forever, really. Not people you want to be mixing with – let me tell you. Although your friend Oscar has to deal with one of them on a daily basis, the poor fella. His principal, Fr Shanlon, is one of the oldest and most powerful around. Older than my brothers and I put together. His real name is Cathbad.’

Benvy could only gape in shock. But from what she

had heard of the lanky priest, it made a certain amount of sense.

Taig placed a log on the fire. It crackled in harmony with the river. The sounds of the place were all so musical: Taig’s voice, the water and the wind in the pines. It soothed her greatly.

‘As for tomorrow,’ he continued, ‘we have a fairly long walk ahead of us, I’m afraid. We’re in what you would now call Wicklow, in the east. We have to travel south, and fetch my javelin.’

‘So, what exactly am I meant to do with it when I get it? It’s hardly the time for a throwing contest.’

‘It’s not for sport, Benvy; it’s a weapon. One of my father’s weapons, to be exact. But I carried it for many years. And then I had to hide it, in the hope that I would never have to retrieve it.’

‘And why do

I

have to get it, then?’ she asked.

‘To prove yourself, young Benvy. Prove yourself or … well, pay the ultimate price, I’m sorry to say.’

He turned and lay down and closed his eyes. Soon he was asleep. Benvy never spoke, just stared at his back with a mixture of fear and disbelief fixed on her face.

Firecracker bursts of sheet lightning lit the land around

them in flashes of silver. Rain pelted down in the darkness between the bursts, while thunder peeled with threat, like great steel drums slammed by giants. Sean cowered behind Fergus, trying to avoid the worst of the cold wind, but there was no hiding from it. They were already soaked from the waterfall, and so the gale bit even harder. His glasses were coated with rain, so he took them off, pointless as it was to wipe them.

‘Something’s not right,’ the uncle said, his words stolen by the gust as soon as they left his lips. ‘Come on, lad. We need to find some shelter.’

‘Yes, please!’ Sean shouted, but his voice had no weight in the storm. He pulled his collar up around his neck and followed Fergus down from the spiral boulders and into the night. In the light of another bout of lightning, Fergus could see a copse of hazel ahead. He held Sean’s arm and they leaned against the tempest, pushing their way to the cover of the thicket.

They forced their way under the tangle of branches, and at last found some respite in its centre. The gale was broken by the hazel and it covered them from the worst of the rain.

‘There’ll be no fire tonight I’m afraid, lad. Wrap up as best you can and try to sleep it out.’ Fergus pulled out a heavy blanket from his pack. ‘Here, throw this on you,’ he said, handing it to Sean. The boy took it gratefully.

‘What did you mean back there, when you said something’s not right?’

‘I mean this doesn’t feel right, lad. Where we’ve come out, I mean. I hope I’m wrong. We’ll know more in the morning. For now, try to sleep, if you can.’

It didn’t come easily, but after a time Sean slept, albeit fitfully.

When he woke, Sean was still sodden through. The ground beneath him had corralled rainwater into a thick brown puddle, and he had slept in it. He was freezing too. Fergus was gone, but his pack was still there.

Sean was grateful for the spare clothes he had brought, and though they were damp they felt infinitely more comfortable. When he had changed and packed away his wet things, he emerged from the thicket, putting his glasses on and stretching. His stomach growled angrily and so he wolfed down two of his mother’s egg sandwiches. He decided to save the rest for Fergus.

The fields around him stretched away to the horizon, undulating slightly but otherwise fairly flat. Here and there, a grove of trees reached up to the now-blue sky, while several of them leaned over, broken by the storm. A few hundred yards away, the huge rocks of the gateway squatted on the grass, roofed by an immense slab. It was a dolmen, Sean knew, but bigger than any he had seen in books. He wondered why they hadn’t just slept under that.

On inspection, his own books had suffered in the wet; the pages were wrinkled and limp. He decided to dry them out in the sun, and so set them on some hazel branches while he waited for Fergus to return.

It was an hour or more before he spotted the giant’s hulking red frame coming back towards him. For someone so big, he was frighteningly quick; like a loping polar bear, those great strides covered metres in a single step. When he arrived, he went straight into the copse to fetch the bags.

‘I don’t like this at all. We need to move.’

‘Why? What have you seen?’ asked Sean, frightened.

‘I saw a castle.’

‘So? What’s wrong with castles? Ireland’s covered in them!’

‘In Fal, lad, castles shouldn’t have been invented yet.’

Sean struggled to keep up with Fergus, often having to break into a run to match his pace. They headed for the edge of a tall forest, a few kilometres away. Fergus wanted cover, to give him time to think. About halfway, at a small stand of oaks, Sean had to stop.

‘Wait. Wait, please, Fergus. I need to stop,’ he spluttered, between trying to take in deep gasps of breath. He collapsed against a tree and slid to the ground.

‘Not a good place, young Sheridan. We need the forest, and I need time to work out what to do. I’ll carry you.’

And the giant man reached down a great paw to lift the boy.

‘No! No, just a minute, okay? I can go myself. I just need to stop for a minute or I’ll pass out.’

Fergus reluctantly agreed to two minutes, and handed the boy a canteen of water. He paced the edge of the grove, watching out over the flatland, grunting to himself.

When Sean had regained some strength, he asked, ‘Have we come out in the wrong time? And can we get back?’

‘That seems to be exactly what’s happened, yes. I

told

bloody Taig that it was Ardee! I could

kill

him! I pray that I get the chance. As for getting back, I dearly hope so. If I am right in where I think we are, I may know of an Old One who might help us. It’s a big chance, but in this time, this particular fellow was never far from trouble. Right now all we can do is hope. And try to keep out of sight.’

‘So, when are we?’ Sean asked, in disbelief that this question should ever pass his lips.

‘The castle has scaffold, which means it is still being built. But I’d know the style of it anywh–’ Fergus stopped short. ‘Why are you looking at me like that, lad?’

But Sean was not looking at him. And Fergus guessed, when the point of a spear blade pressed against his cheek,

that the boy was looking past him to a man clad in iron armour. The hot snuffle of a horse confirmed it. When more men emerged from behind the trees with crossbows pointed at him, he knew they were in serious trouble.

A

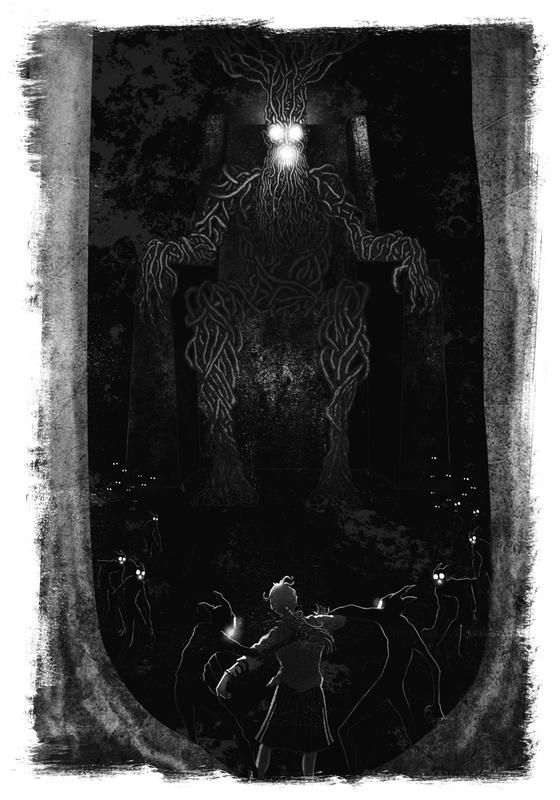

yla had scuttled, crawled and clambered until every muscle was in spasm and her stomach swirled with fright. The passages seemed to branch off more and more; she could feel the openings along the cold walls, and she chose at random, in the hope of losing the creatures. Their screeches came from ahead and behind now, and desperation chilled her blood. She had no sense of getting anywhere, only of scrambling hastily to avoid capture. She had begun to slow, and then, despite begging herself for more strength, Ayla had to stop again. There was silence. She kneeled and closed her eyes.

When she opened them, Ayla was surprised to be able to make out her surroundings in the darkness.

My eyes are adjusting at last

. She could just see the walls of the passage, in places hewn from the rock into a rugged shaft, in others a mass of thick, writhing roots. She squinted and pulled

herself to stand on quivering knees, curious to inspect the walls closer because –

yes

– where the roots gave way to stone the walls weren’t just hacked at. They were lined with intricate patterns; long, thick lines interwove in an impossibly complex dance. As she ran a finger along one of the stones, she found to her horror that it ended in a fearsome face, with large, pointy ears and two wide, deep holes for eyes. Stepping back, she could see now that every surface was detailed with the same horrible mural – a twisted depiction of writhing goblins: portraits of her jailers.

Ayla knew that she would have to move again soon, but saw no point in blindly scurrying any more. There seemed to be a respite in the chase, and she needed to take advantage of that; she needed to take stock. Ahead, the passage rounded a corner. Just before the curve was an opening – a small one, more like a big crack in the wall. Behind her, it narrowed and dropped to the labyrinth she had just come from. There was no sense in going back there. She crept towards the corner, mindful of making any noise.

The details on the walls became clearer now, and the gloom began to lift. Her stomach twisted inside her when she realised why this was. Edging one eye just around the corner, she saw the passage widened, illuminated by torchlight. Gathered at its end were at least twenty of the creatures. She couldn’t stop the gasp coming out of her, or the scratch of her foot on the ground as she jolted back

from the corner. The wail came loud and long, piercing her bones. The others barked in unison, and one of them hissed: ‘CAUGHT YOU, LITTLE RAT!’

Ayla made a dive for the little gap, cutting her sides on its edges as she forced herself through. She hauled herself down a tight shaft, choking on dust, which fell in sheets as she moved. The howls reverberated after her. After a few yards, the decline steepened and, unable to stop herself, she slipped down off an edge and fell headlong into the dark, plunging with a shock into an icy pool. The breath was ripped from Ayla’s lungs with the sting of cold, and she stood in the knee-high water, gasping.

She looked around frantically. It seemed there was nowhere to go. The shaft above her flickered orange from torchlight. The high ceiling descended in a curve to the pool, stopping just a few feet above the surface. It looked like the pool continued down a low tunnel.

There was no other choice. She waded towards the overhang, the water climbing to her waist. By the time she was underneath the overhang, the water was up to her armpits and her jaw shuddered uncontrollably. The first set of glowing-white eyes appeared behind her at the shaft. She was about to take a deep breath and dive under when something coiled around her ankle, gripping it painfully. Before Ayla had a chance to wonder, she was wrenched violently under the water and into the darkness.

The knight’s spear point never left Fergus’s cheek as they walked. Neither did the nine crossbowmen ordered to surround him, marching in a circle with their bolts poised and pointed at his chest. Sean had just one such guard – a plump one, who didn’t seem much older than him.

The knight, obviously in charge, had spoken in a language Sean didn’t understand – a kind of guttural version of French. But he had seen their distinctive helmets before; they sloped up to a round peak with a single plank of metal covering the nose. Their captain, the one who held the spear so steadily at Fergus’s face, was the only one on horseback. He wore the same chain mail as his men, but over it was draped a red tunic, fastened at the waist with a wide leather belt. It had three black lions stitched onto the front. At his side he wore a sword with a stubby handle, and from his horse’s flank hung a long shield, shaped like an upside-down teardrop. He kept speaking to Fergus, but the big man said nothing. Eventually, the captain’s patience ran out and he jabbed the spear, cutting a slice into Fergus’s cheek from temple to jaw. Fergus stopped walking. He spoke to the captain in his own language.

‘Sean, lad,’ he said over his shoulder when he had finished, ‘they think I’m a wizard and you’re my apprentice.

For the moment I’m not letting him think any different. They’re going to take us to the keep. Just keep quiet and follow my lead. Got it?’

‘What did you say to him just there? And how do you know their language?’

‘I told him he’s going to pay for cutting me. And it’s not my first time picking fights with Normans.’

Muddy faces peered out of fragile-looking huts of wattle and thatch, both curious and frightened. Beyond their straw roofs, the keep loomed on a hill like a sentinel, washed in red by the evening sky. It was indeed in the process of being built; rickety wooden scaffolding surrounded it, and builders still clambered as daylight faded. A tall fence of pointed wooden stakes, with a huge gate, stood around the perimeter, and more men with crossbows paced along the top.

The high gates opened with a groan, and they were ushered in. The grounds around the keep were thick with mud, dimpled by horse prints. Stalls were dotted around, housing chickens in cages and rabbits hung by the hind legs. Cattle lowed noisily. There was activity everywhere as people traded, talked, bartered and argued. The chime of a smith’s hammer drew sparks from an anvil as he beat a red-hot horseshoe. There were pillories too, where one unhappy soul hung limp, his head and wrists held fast by a heavy block of timber. Everything stopped when they

entered. Eyes bore through them as they were marched up stone steps and through the huge doors of the imposing grey fortress.

Inside was a grand hall, lit by flickering torches. The high walls were draped in tapestries, showing a hunt, a battle and, ominously, thought Sean, a hanging. Long tables ran up either side, with servants bustling in and out from doorways hidden in the gloom. At the far end, another long table faced them. Behind it, a high chair held a small, fat man with a bowl haircut and rings on each finger. He was flanked on either side by two other men in similar clothes, who leaned and whispered into his ears. There were soldiers everywhere. At the sight of Fergus an order was barked, and reinforcements flooded the hall.

The fat man addressed them in the same throaty French dialect, and the captain responded. Fergus said nothing. He had bled quite a bit from the wound on his cheek, and it had congealed in the brush of his red beard. Sean thought, for the first time ever, that he looked slightly weakened. When the lord and his captain had finished, the little man dismissed them with a flick of his bejewelled hand, and they were left surrounded by guards.

‘What’s happening, Fergus?’ asked Sean, frightened.

‘We’re going into the pillory, lad,’ the big man replied. ‘And then we’ll be hung.’

Before Sean could respond, he was jabbed violently in

the back by something sharp, and they were pushed out of the great hall and out to the bailey, where the last of the daylight was giving way to night. Torches were lit and handed to the guards, who forced them over to a wooden platform that held the pillories high up for all to see. Sean wondered why Fergus, so fearsome, was letting this happen. He couldn’t stop the tears from coming.

‘Fergus? What …’

‘Silence!’ growled a guard in French, and hit Sean on the shoulder with the butt of his crossbow.

Fergus just looked at him and shook his head, placing his own neck and wrists on the rough grooves of the pillory. The heavy beam was lowered over him and chains run through the steel rings. Sean was kicked in the back of the legs and then hoisted roughly back to his feet. His head and arms were thrust into place aggressively. The wood gnawed at the skin, and already he bled where it chafed. Forcing his eyes up, Sean could see a crowd gathering.

The first cabbage hit the board just by his head, exploding in shards of green. The second didn’t miss and his glasses were knocked to the floor of the platform. They were pelted, and not just with fruit. Some picked up bits of slop from the ground and hurled it at them. All the while the guards watched the crowd. Through squinting eyes, Sean was sure he could just make out one guard push a girl into action, pointing his crossbow at her until she reluctantly threw a

turnip. After fifteen minutes of this, the crowd dispersed and night fell, fully. Sean found he couldn’t help crying.

‘Ah now! Fergus! ’Tis yourself!’ said a voice from the other pillory.

Sean blinked in shock, and his tears stopped.

‘Ah, Goll, how’re things? Just the man I was hoping to run into,’ Fergus said, feigning calm, but a quiver betrayed his relief. ‘I thought I might find you here.’

‘Eh, what is going on?’ asked Sean.

‘Sean Sheridan, meet Goll. Goll, meet Sean Sheridan.’

‘Pleasure,’ came the voice.

‘Goll is going to help get us out of here, aren’t you, Goll?’

‘Ah, sure,’ came the reply, ‘why not, says you!’

Ayla slowly started to come around to the strangest sensation. Unsure if it was a dream or not, she didn’t open her eyes. She thought she was in her bed and one of her uncles was sitting on her as a joke. But it wasn’t funny; it hurt. And she found it hard to breath. From the waist down she was pinned, tightly.

‘Get off me, Fergus,’ she murmured drowsily, trying to summon the strength to wake up. ‘It’s not funny. You’re hurting me.

Ow

!’

The last bit hurt a

lot

. She was fully awake now, and opened her eyes. It took her a second to make out what was happening, and when she did, she screamed long and loud in horror.

Around her waist were clamped two huge, fat, slimy lips. They advanced up her stomach hungrily. Above the lips, bulbous green eyes blistered out from a head that oozed with gunk. The fluid erupted from pores and warts all over its skin; they gurgled and gushed, occasionally popping with a sickening fizz. It was fat and wide and smelled horribly of tepid water. Translucent lids flicked up from the bottom of its eyes, first one then the other. It was an enormous toad.

Ayla howled and thrashed as much as she could. She bashed the thing on its nose and scratched and clawed at it, but it paid no heed to her, only swallowed faster. She tried desperately to reach its eyes, but they were too far back now. She kept hitting and punching, but the lips were nearly up to her shoulders and she couldn’t breathe. She started to pass out again.