A Child Al Confino: The True Story of a Jewish Boy and His Mother in Mussolini's Italy (2 page)

Read A Child Al Confino: The True Story of a Jewish Boy and His Mother in Mussolini's Italy Online

Authors: Eric Lamet

The crux of

A Child al Confino

centers on young Lamet's and his mother's struggles in backward Ospedaletto. Urban sophisticates, they faced often-arduous adjustments to harsh new climes, new customs and cultures, and new language systems — the often impenetrable dialects of the Italian mountain communities. Once residents and part owners of a premier Viennese hotel, they were now straining to find suitable housing, to scrounge for food and to procure some sort of education for twelve-year-old Eric … all futile searches, as it turned out. Lamet echoes the observations of other internees, notably Carlo Levi and Natalia Ginzburg, both Italian-Jewish authors and former

confinati

; Lamet's memoir, like Levi's

Christ Stopped at Eboli

and Ginzburg's

It's Hard to Talk about Yourself

, notes that relegation to the primitive mountain

confino

villages was akin to stepping back in time.

Just as mother and son struggled, however, they also were favored with new friendships and new ties. Lamet's portrayal of the ragtag group of Ospedaletto

confinati

characters at times amusing, endearing, and maddening. It also introduces Pietro Russo, a fellow exile who had such a profound impact on Lamet's life that he dedicated this memoir to him.

In the fall of 1943, General Mark W. Clark and his Allied troops began Operation Avalanche, the long slog up the Salerno coast that eventually liberated southern Italy. Eric and his mother rejoiced at their liberation by American soldiers that October. At the time, they could not have known that in a strange twist of fate

il confino

had saved their lives, for had they been interned in northern Italy they would have come under the jurisdiction of Nazi troops and most likely would have found themselves among the 7,000 Italian and foreign Jews who were deported to Auschwitz and other Nazi

lagers

. Of those deported, only three hundred Italian Jews and five hundred foreign Jews survived.

Eric remained in Italy until 1950 when he, his mother, and her second husband — that same Pietro Russo — settled in the United States. His memoir traces a little-told story: of child refugees in Italy, of foreign Jews in Italy during World War II, of the hardships imposed by the

confino

system, of the southern Italian mountain villages, and of the mutual respect that often developed not only among

confinati

but also between unsophisticated peasants and urban intellectuals both struggling under adversity.

CHAPTER 1

Escape from Vienna

S

tunned, peeking from behind the hallway wall for the longest moment, I watched my father rapidly pacing the four corners of the living room floor. I could tell he was very tense. Never changing his fast rhythm, he was mumbling in such a low tone I couldn't tell whether he was speaking German or his native Polish.

We had eaten our breakfast hours before, yet my mother was still in her silk robe.

Mutti

's hair lacked its usual neatness and her face was drawn and without makeup. She sat stiffly against the wall on one of the dining room chairs. While her eyes followed my father's every step, I could tell that her mind was far away, immersed in other thoughts. Never, until that awful morning, had there been such an upheaval in my well-ordered, carefree life of nearly eight years.

What did I do?

was the only thought running through my mind.

Did my teacher send home a bad report

? I was certain they were discussing what punishment I deserved, something they had never done before.

“What happened?” I asked meekly voicing words that had crossed my mind moments before, instantly sorry to have said anything and hoping not to have been heard.

Neither of my parents answered. Often I had felt bothered when my parents failed to notice my presence but, this time I was glad they hadn't. In my frightened state, I felt relieved not to have to cope with their answers.

That morning, for the first time,

Mutti

had not helped me to get dressed. She had come to my room at the usual hour and sat on the bed. “You're not going to school today.”

“Why not?”

“Please, don't ask questions.”

Now, my mother's nervousness of earlier that morning was more intense. I watched as her foot delicately tapped the parquet floor, her hands tightly clenched her knees, showing the white outline on her fair skin.

Millie, our housekeeper as well as my governess, walked into the dining room to set the table for the midday meal and my father stopped pacing. Millie always moved about the house with a bounce in her step, humming some Austrian folk tune; now she worked in silence. The sight resembled a movie scene in slow motion:

Mutti

sitting motionless and staring into space, Papa awkwardly standing still on the spot where he last had placed his foot, and Millie moving about as if unaware of our presence.

Though I was not quite eight, I had already learned to stay out of my parents' way when something unusual was going on. What was happening was more than unusual; it was downright scary. Perhaps it was best to make myself invisible. Creeping backward toward my bedroom all the while trying to guess what could possibly have happened to cause such gloom, a bizarre thought crossed my mind: I wished I could have been in school with the teacher I detested, doing assignments I liked even less.

From my doorway I watched as Millie left the dining room and Papa resumed his pacing. I quickly returned to my room and, cuddling my teddy bear, I lay on my bed and cried quietly.

Soon after, I heard my parents' loud exchange. Driven more by curiosity than fear, I walked back to the living room. They were shouting in Polish, a language I could understand when spoken slowly and calmly. And as they did neither, I understood nothing. But I could tell they were not fighting with one another, as they had done many times before and that was a relief for me.

“I'm glad you're here,”

Mutti

said. “I was just going to call you. Come S

chatzele

. Lunch is ready.” Her tone had none of the pleasantness I so loved.

As though nothing had happened to give rise to the strange behavior I had witnessed all morning, we sat at the table to eat the main meal of the day.

“Millie,”

Mutti

called. “You may start serving.”

Sullen, Millie entered, placed a silver-plated soup tureen on the table, then turned on her heels and left. Never had she acted like that before. My ever-smiling Millie had always served each of us. No one ever had to ask her. She had loved doing it. Papa was about to say something but, my mother looked at him and with one finger across her lips, motioned for him to be silent. Then she shrugged her shoulders and did the serving herself.

We sat in silence. I waited for the storm that was certain to come.

“Why aren't you eating?”

Mutti

asked.

Her words caught me off guard. Trembling, I started to cry. “I'm scared,

Mutti

. I don't know what's happening.”

She placed her arms around me, pulled me close, and stroked my hair. “Erich, one day you'll understand.” As she spoke, I saw tears well in her eyes. “Yesterday German soldiers invaded Vienna.” It was March 14, 1938.

My mother was right. I did not know what it all meant. Still I felt threatened. What did it mean that German soldiers invaded Vienna? Who were these German soldiers? I wanted to ask these questions and more but, somehow did not dare.

We had just finished lunch when

Mutti

suggested I take my daily rest. “Go,

Erichl!

”

I usually loved it when she used the pet name

Erichl

, but this time it did not seem to matter much.

A blaring radio jolted me out of my nap. The noise had to be coming from neighbors across the courtyard. No one in our home would turn on the radio right after lunch when we were taking our afternoon naps. Nor would my parents, out of concern for the other tenants, allow the volume to be so loud. Strange music screeched from the speaker, mixed with a man's voice more loud than understandable. Crowds screamed in the background. I got up to see where the sound was coming from.

In her colorful Austrian

dirndl

, the costume she wore only for special occasions, Millie sat transfixed in front of our radio. She had pulled a dining room chair into the antechamber, next to the small table on which she had placed the much-too-large receiver. It looked dangerously close to the edge and almost ready to fall. And that chair? No one had ever moved those chairs out of the dining room. Millie knew it wasn't allowed. What was going on? She seemed hypnotized and unaware of my presence.

I walked up to her and placed two fingers on the volume knob. Without a glance, Millie grabbed them and pushed them away with such force as to crack the small bones and make my hand go numb. I was in shock. Was this the gentle and loving Millie in whose bed I cuddled many mornings before going off to school, preferring hers to my mother's? I wanted to cry out but, her meanness made me run away and look for safety inside my room, where I buried my face in the soft down pillow.

That evening the situation grew still more troubling. Millie was nowhere to be seen and my mother was left to bring dinner to the table herself. My parents hardly spoke and I, grasped by the fear of the unknown, did not dare utter a sound.

After dinner,

Mutti

moved our dishes to one corner and pulled her chair next to mine. She cleared her throat and I, though looking at my father, spoke to me. “Listen to me carefully, Erich. I don't want you to go out of the house. I don't want you to speak to Millie or anyone in the building. I don't want you to listen to the radio, and you will not be going to school for the next few days.” From her tone and my father's nodding approval, I knew none of this was open for discussion.

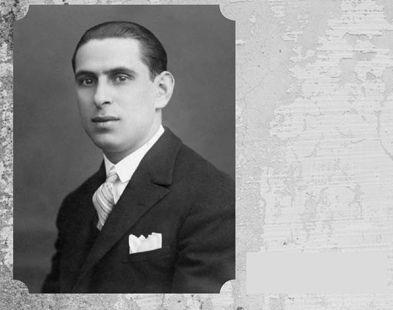

Eric's father, Markus Lifschütz, in 1928.

Between 1930, the year I was born, and 1938, my family had enjoyed a comfortable lifestyle. Papa, with his younger brother Oswald — my Uncle Osi — managed the Hotel Continental. It must have been a first-class hotel since many rich and elegant foreigners came to stay. I thought the hotel was ours but, later learned it was owned by my granduncle Maximilian, who had made a small fortune when oil was discovered on his land in the Ukraine. From my parents I learned that Uncle Max, who was my grandpa's brother, was a generous man who shared his good fortune with members of his family. With the proceeds of the sale of his oil fields, he had purchased real estate in several European countries then let a number of his relatives benefit from some of the revenues these investments generated.

After my parents married and for the first four years of my life, we lived at the hotel, where my mother enjoyed many comforts: built-in babysitters, laundry service, daily maid help, and two restaurants with room service. Well-to-do families without children found it convenient to live in a hotel in those days. The Continental had suites with kitchenettes and living rooms and it offered services and comforts not found in private homes. A number of my parents' friends had taken up residence at the hotel.

Cooking and baking were my mother's loves, and since living in the hotel made it difficult to satisfy her longing for those passions, we moved to our own apartment in 1934. I had liked living in the hotel. It was the only home I had known. My friends were all there: the bell captain, the concierge, the waiters, the chambermaids, and some of the regular guests. I wasn't anxious to change. So I asked

Mutti

why we had to move. “Growing up in a hotel is not good for a child,” was her answer.

We stayed in our first apartment for the year I attended kindergarten, but as soon as I was ready to start first grade, we moved again, this time to larger quarters on the Tabor Strasse. The hotel was on the same street, right on the corner intersecting the Prater Strasse, no more than 200 yards away. For Papa this was very convenient. He could walk to work, come home for lunch, take a short nap and be back at the hotel for the remainder of the day.

Mother's lifestyle was typically Viennese. In the afternoon, almost ritually, she met her friends at the Kaffee Fetzer where, after an exchange of gossip, she played bridge until evening. After dinner at home, many of these same women met again, this time accompanied by their husbands, to socialize in one of the many coffeehouses for which Vienna was famous.