A Child Al Confino: The True Story of a Jewish Boy and His Mother in Mussolini's Italy (3 page)

Read A Child Al Confino: The True Story of a Jewish Boy and His Mother in Mussolini's Italy Online

Authors: Eric Lamet

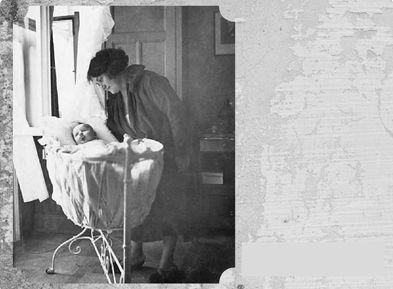

Eric's mother, Carlotte Szyra Brandwein, in 1928.

Our first apartment was across the narrow street from the Kaffee Fetzer. Often I walked over to see

Mutti

, not out of any interest in her friends or the coffeehouse, but because I liked the candies one of her lady friends frequently brought with her. Once that friend sent me to the candy store around the corner.

“Please get one-quarter pound of chocolate-covered orange peels,” she said.

Convinced the woman intended the candies for me, I asked the clerk to let me taste one before placing the order. I cringed. “Too bitter,” I said.

“May I get you something else?” the clerk asked.

“Yes, I'll have those,” I pointed at the pralines.

When I returned with the wrong candies, the ladies looked amused and I did not get scolded. Not even

Mutti

was annoyed. The lady, who had given me the money, took her change. “It is perfectly all right,” she said. “You may keep the candies for yourself.”

Eric at three weeks, June 1930.

Eric at age one with his mother in Semmering, 1931.

Mine was a happy, orderly life that revolved around my Millie, two-month-long Alpine summer vacations on the Semmering with Mother until I was about four, yearly visits with my grandparents in Poland, and weekly afternoons with

Omama

, my maternal grandmother. I also had many friends near my own age; we played in our courtyard and shared mutual birthdays. Oh, how I loved the chocolate pudding with sliced bananas, a favorite at any birthday party. Then there were our relatives, who made a great fuss over me, for I was the only child in the family's Viennese contingent.

During the four days following March 14, our lives changed dramatically. I stayed home with

Mutti

while Papa came and went more often than usual. My parents endured Millie's many disrespectful actions. Because of the disturbances on the streets, no one shopped for groceries that Monday and, since we had no means to keep food cold, by Tuesday we had little in the house to prepare for a meal.

“Millie, would you go to do the shopping?”

Mutti

asked.

Millie's tone was insolent. “I'm busy right now. I'll do it when I have time.”

I couldn't believe my ears. What had happened to her respectful “Of course, madam, right away”? At twenty-two she had lost all her good manners. Mother would never have tolerated that tone from me.

The radio, the volume blatantly turned high to show Millie's newly asserted independence, blared throughout the apartment. In the streets people were chanting and marching, but I did not know what was happening because my ever-watchful mother made sure I did not look out the window.

Millie was allowed to take off more time than ever before. Well, not really allowed. She didn't ask, merely announced, “I will be going out for the day.”

“When will you be back?”

Mutti

asked.

“Whenever I get back.”

Mother never asked that question again.

Millie's absence gave my parents the freedom to talk openly. They would ask me to leave the room, but even though I did, I could not help but overhear when their voices rose. In their eyes I knew I was not old enough to be trusted with the gravity of our situation, yet I was old enough to sense it was really serious.

“They're rounding up Jews and taking them into cellars,” my father said. “I don't know what they are doing, no one knows, but I hear horrible stories. Someone said they have stopped Jewish women on the streets and forced them to use their fur coats to wash the side-walks.” When I heard that, I thought of my

Mutti

and could not imagine her complying with such an order.

“We must leave!”

Mutti

said. She was a woman of action, always in charge of our family. “With our Polish passports, we'll be able to leave Austria without any trouble.”

In spite of living in Vienna for more than twenty years, my parents had never given up their Polish citizenship.

We must leave?

I repeated to myself. What did that mean and where would we be going? I spent most of the next four days in my bed whispering to my teddy bear and trying to read. I felt like a prisoner waiting for his sentence. The fear of the first day mounted with every passing hour.

On March 18, five days after the German troops had marched into Vienna,

Mutti

came to my room to tell me we were going to Poland. Her face was pale, her eyes swollen and red.

“Do we have to?” I asked.

With a forefinger placed on her lips, she signaled for me to remain silent. “

Opapa

is ill and has asked us to come visit him.” Her voice was unnaturally loud. I couldn't understand why she had raised her voice so much when I was standing close to her in the same room.

“We were …” I started, but Mother placed her full hand over my mouth.

I had always looked forward to visiting my grandparents, but this time was different. The brand new sleigh I had craved for so long was finally mine, a surprise gift from my parents on Saint Nicholas Day, a day considered by many in Germany and Austria as a gift-giving day without religious connotation. The sleigh was leaning against the wall in one corner of my room. Every morning I could see its shiny wooden slats and bright runners. I had used it only twice. Going meant I would not be able to use it and the parks were covered with fresh snow. Nor would my teddy bear be allowed to come with me.

Mutti

had never allowed me to take him on previous trips. A family friend had bought the stuffed toy before my first birthday. When placed into my crib, the docile bear — larger than I was — provoked such screaming that my parents stored him in an armoire and out of sight for months. Now having to leave Teddy behind was the thing I disliked about our trips to Poland.

Through free-flowing tears, I tried to cajole my mother into relenting. “Just this time. Please,

Mutti

.”

“The answer is no.”

Although her voice had a determined tone, I was not deterred. “Why not?”

She looked tired, drawn and annoyed at my persistence. “Just do as I tell you. Please.”

Dashing from the room to get away from her, I shouted, “I hate you!”

Millie kept sitting in the anteroom. In those last four days she had spent so much time listening to the radio that she had done nothing else around the house. Worse yet, she, who for the past three years had been my solace and comfort, was now coldly indifferent to my pain. Two months and thirteen days from my eighth birthday, in our own home, surrounded by the people I loved, I felt alone and abandoned.

Eric's grandfather

Opapa

with Uncle Norman in Lwow, Poland, in August 1939, less than one month before the German invasion.

Later that afternoon, my parents exited the bedroom. Father, in his fur-lined overcoat, carried two suitcases. Mother, wearing not her fur coat but her cloth overcoat, tried to be warm and friendly.

“Millie,” she said, “we will be gone for only a few days.”

The young servant never looked up. She seemed not to have heard.

My mother stood silently for more than a moment. “Here is money in case you need to buy something for the house. If you need anything else, you know you can call the hotel.”

The woman made no attempt to reach for the money. Mother placed it on the table, near the radio. As she did, she spotted the daily paper lying on the floor. Staring at her was a full-page picture of Adolf Hitler. Abruptly my mother turned to my father.

“Get a taxi and make sure you find one flying the Nazi flag.” Her voice had a slight quiver.

Papa was back a few minutes later. We were ready to leave and, as I walked backward toward the door, my eyes remained focused on Millie. Oh, how I loved her and I was certain she loved me. Why else would she have taken me to spend the past two summers at her parents' farm? I stopped and waited.

Very softly, hesitantly I called: “Millie.”

She never raised her head to look at me.

Mutti

grabbed me by the arm. “Let's go!”

Life was so cruel! I was leaving behind my Millie and my Teddy. I didn't know one could hurt so much inside. The taxi was waiting. Its front fenders flew two small red flags bearing a strange black cross similar to the Austrian cross. Once we were in the car,

Mutti

told me what a swastika was. The driver held the door for my mother. She stepped in, immediately lowered the side curtain and fell back onto the seat. I didn't know whether she wanted to avoid seeing what was going on outside or to prevent anyone else from seeing us inside.

During the ride I stole some glimpses of the outside world. A circle of agitated people surrounded two kneeling, well-dressed women washing the sidewalk.

“What are they doing?” I asked.

My father made a small opening in the curtain and glanced out. He leaned over to Mother and, with a hand cupped over his mouth, he whispered. “Just what I was telling you. They want those poor women to rub off the oil-painted Austrian symbols with their furs.”

I remembered having asked my father why all those Austrian emblems had been painted on sidewalks and bridges. “To celebrate the new year,” he had said.

The cab dropped us off at the main entrance of

Südbahnhof

, one of the city's train terminals. The driver lifted our two suitcases from the luggage rack and placed them on the curb. Papa looked around for a porter but none was in sight. “Take the bags and let's go!”

Mutti

said, nervously.

The railroad station, with its hollow-sounding interior, was not as I remembered it from our previous trips. Soldiers were everywhere. Prominent on the sleeves of their black uniforms was a red armband with the same funny looking black cross that I had seen on the taxi's flags.

“My God, we're surrounded by the SS,”

Mutti

whispered. I noticed that she trembled.

“What is SS?” I asked.

Mother ignored my question. My father put the suitcases on the floor of the large hall. It was March, still winter in Vienna, yet perspiration had formed on his forehead. He had carried the luggage up the long stairway and halfway into the hall and now stood there out of breath. I had hardly ever seen my father lift anything heavier than a glass of water.

He used his breast-pocket handkerchief to wipe the sweat off his face, then walked away, leaving us standing there. Mother paced stiffly around the two valises. Soon Papa returned, escorted by a soldier in that sinister black uniform.

The man, apparently an officer, turned to my mother, clicked the heels of his highly polished boots and raised an arm in a snappy salute. “

Heil

Hitler!” he blurted.

My mother nodded and smiled.

“Follow me,” he said. Walking with a distinct Prussian step, the soldier led us to a far corner of the station.

“Can you believe this?”

Mutti

mumbled. “Still trying to be chivalrous — even to a Jewish woman?”

“

Sai sha

,” my father shushed her in Yiddish.

More soldiers than travelers filled the immense hall. Echoes reverberating throughout multiplied the harshness of each sound. Men and women wearing the same menacing black outfits constantly clicked their heels and raised their arms in that strange salute. Each click of the heavy boots bounced off the distant walls and the high ceiling, creating a deafening clamor. I felt like we were surrounded by a whole army.