A Child Al Confino: The True Story of a Jewish Boy and His Mother in Mussolini's Italy (33 page)

Read A Child Al Confino: The True Story of a Jewish Boy and His Mother in Mussolini's Italy Online

Authors: Eric Lamet

“This is even better than the pasta Signora Dora makes,” I said. The cook found butter and Pietro savored the fresh sole. His eyes ate each morsel before his mouth did. I saw how he lost himself in the flavor of that fresh fish and was amazed at his taking such delight in eating. Fascinated, I stared, letting my own food sit before me.

“You like fish?” I asked.

“This is what I miss most. At home I have fish every day. But you better eat or your food will get cold.”

Our train back to Avellino was not due until 3:00, allowing us to linger at our table in the April breeze. We enjoyed Mount Vesuvius in the distance and the Isle of Capri rising from the shimmering blue waters of the gulf. I saw firsthand the splendid panorama of Naples and understood the popular saying I so often had heard: “

Viri Napule e po' mori

.”

That one-day trip to the Parthenopean city was my first and only holiday from our confined and Spartan life.

Don Antonio

F

rom the small village square one morning, I heard a choir practice. Always curious, I followed the sound, walked up the little knoll, and into the church.

Don Pasquale noticed me from the balcony. “Do you like to sing?” he asked.

“I love to. I sang in a synagogue choir in Vienna.”

“I need boys in my choir. Only seven come regularly. Why don't you join us?”

I hesitated. Me sing in a church? A Jewish boy? It had to be better than doing nothing. Mamma would not object. It would keep me off the street. “Sure. When do you want me to start?”

“Come tomorrow for a tryout. Four o'clock.”

Without telling my mother, I went back to the cold church the next day and found Don Pasquale playing the organ. “Don Pasquale,” I called out. “I'm here!” My words echoed in the cavernous space.

“Come up,” he shouted from the organ balcony.

The few thin rays of light peeking through the high windows, darkened by age and by dampness from years of unheated air, created a ghostly feeling. This gloomy church would not have been my first choice of where to spend time. On days when boredom weighed heaviest, I grasped at any new experience. Up I climbed the narrow, circular metal steps, following the direction of the priest's voice.

“Welcome, welcome, Enrico! I'm so happy you've come. I always need people for my choir. It's so difficult to get boys to come. They would rather run on the streets.” He handed me a well-worn music book. “Can you read music?”

“No. I've never learned. When I sang in a synagogue, I just followed the music.”

“Well, just look through it. You'll be able to learn.”

A vision of

Mutti

leafing through the book with all the references to the Holy Mary, Jesus Christ, and the Holy Spirit flashed through my mind. Loud and clear I could hear her caustic comments and, even funnier, I imagined the eloquent facial expressions she would make. A big grin crossed my face. It was too dark for the priest to have noticed or surely he would have asked me to explain. As long as he didn't ask me to make the sign of the cross and take communion, I could live with the words in the book.

He asked me to sing a few notes to his accompaniment. “That will do just fine,” he said. “I'm happy to have you join us.” He informed me when rehearsal time was and with an enthusiastic handshake, sent me on my way.

I had turned six when

Mutti

heard me sing in the synagogue in Vienna. Would she now come to church to hear me? Never! When I told Mamma, her reaction was milder than expected.

“I'll make believe I don't know anything about this. My son singing hymns in a Catholic church. This is worse than when you almost joined the Italian army.” Then, with hands held together in prayer, she fixed her eyes to the sky. “Dear God, please forgive my

meshugene

son.”

I would have liked for my mother to have heard me sing and see me wear my embroidered white cassock, but maybe it was better she didn't. It was unthinkable to have her Jewish son sing in a church, but, to see him dressed as an altar boy and hear the names of Catholic divinities come from his lips would have been like planting a dagger in her chest.

For several months I donned the white cassock and sang with the all-male choir. The weekly choir practice occupied a few hours and helped develop my rapidly changing voice.

Among the many people who befriended me in Ospedaletto, Don Antonio was the most provocative. The priest was strolling through the village with Pietro when I first met him and at once I was captivated by the tall man's charisma.

“Enrico has become a friend of Don Giuseppe,” Pietro said. “Isn't that true?”

“We have good debates,” I added.

“Well, perhaps you and I should get together and have a debate,” Don Antonio said.

Don Antonio, born into an old-fashioned religious family, had been honored to become the village monsignor at the young age of twenty-four.

“It was my greatest dream come true,” he said. “In those days I wanted nothing else but to be a monsignor. I wanted to do homage to my father's memory and make my mother proud.”

But his life's dream was no sooner realized than this intellectual rebel began to distance himself from the constrained lifestyle of his family, the village, and the church.

His mother and sister always dressed in black as a sign of mourning for the priest's father, who had died many years before. Their hair, neatly combed into a chignon, was in stark contrast to the dirty feet that showed through the open

zoccoli

and which matched the accumulated dirt under their fingernails. Every day they walked to church down the unpaved, dusty road, nodding discreet greetings to those they passed on their way. Their religious ardor and attire were typical of women of a southern Italian village.

Don Antonio differed so much from his mother and sister that it almost seemed they could have been born in different eras. Nothing about him was characteristic of this village. Not his proud bearing. Not his secret wardrobe. Bright, intelligent, he had caught the attention of someone from the Vatican when still a novice and was transferred to a job in Rome. “I was delighted to go to the Eternal City.” He also confided how he soon found an apartment and a lover, not necessarily in that order.

I wasn't quite sure what a lover was and, after his cautious explanation, my curiosity overrode my better instinct and I risked asking, “Isn't that against the laws of your church?”

Perhaps as a subtle rebuff, Don Antonio ignored my question, making me realize that I probably should not have asked.

During one of his visits to Ospedaletto, with youthful enthusiasm, this thirty-year-plus Catholic priest showed me a suit he had recently purchased. Index finger on his lips, he whispered, “Shhh. No one is to know about this.” As a kid of twelve, I felt uneasy being this sophisticated man's confidant until I found out that most of the

confinati

already knew, for this

simpatico

man was incapable of keeping his own secrets. A tall, good-looking, affable, and quiet rebel, he loved to wear civilian clothes in disregard of the church's precepts, for, as he had boasted to some, he had cast off his celibacy long before.

I enjoyed spending time with Don Antonio. His exquisite Italian, without a tinge of the local dialect and the worldly knowledge he was willing to share made up for the musty odor in his mother's house.

“Where do you wear your civilian suit?” I asked.

“When in Rome.”

“Oh, tell me about Rome, please.”

“

Roma. Bellissima

!

La Città Eterna

!” He let out a sigh as his eyes gazed at the ceiling. “There, antiquity merges with the present. It's incredibly magnificent. A majestic city that would be even more majestic if Mussolini were far away from it.”

“You don't like

Il Duce

, do you?”

“Why should I? Because he drained the Pontan swamps and made the trains run on time? What about Ethiopia, Eritrea, Libya? But I better stop before I get myself in trouble. Tell me, what do you remember of Vienna?”

“Not much. We owned a hotel. I loved going to the Prater, the Vienna amusement park. Oh, yes. I enjoyed going to the Lilliputian village there.”

“What's that village?”

“In the Prater there was a whole colony of midgets, Lilliputians. They lived in their own tiny houses, had their own shops, a church, and a little theater. The houses were so small that even, when I was six, I had to stoop to get through the doors. Once I saw a couple get married and in their tiny theater I learned a skit. Do you want to see it?”

“Of course. Go ahead, show me the skit.”

I mimed sewing an invisible garment and then losing the imaginary needle. Rising from the chair, I looked for the needle and, unable to find it, sat again. The needle, hidden in the chair, implanted itself in my behind and made me jump up with a scream. We both laughed.

“That was good, very good,” he said.

Don Antonio was great to be with. He spoke to me as an adult, always ready to enlighten me on many subjects. That day I got him to tell me how Mussolini, without provocation, had attacked Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Libya.

Clara Gattegno was tutoring me, yet Mother still worried I was not studying enough. Alfredo Michelagnoli had arrived recently in our midst, and before long my mother asked him to teach me English.

Never one to accept without question what my mother had chosen for me, I raised my objection. “I'm studying with Clara and that's enough for me. Besides, Jimmy doesn't have a tutor.”

“I really don't care what Jimmy has or doesn't have. His parents will have to worry about that. I want my son to have as much knowledge as possible. Just remember one thing,” Mother said, pointing a finger to her head. “Nobody can take away what you have in here. When we left Vienna, we had to leave everything behind. Do you remember? But what I learned as a child I took with me. Learn,

Schatzele

! Learn all you can, for your knowledge will stay with you for the rest of your life!”

A professor at Oxford at the outbreak of the war, Alfredo Michelagnoli was forced by British authorities to return to his native Italy, where the Fascist government, citing his British connection, interned him, his wife, and his two young daughters. Wearing tweed knickers, a matching beret, and riding boots, he looked the part of an English country gentleman. He changed his clothes often, but his beret remained the same, serving as a cover-up for his premature baldness as well as a stylish article of clothing.

His walk was more like a duck's waddle. Adding to this learned man's almost comical image, Alfredo also suffered from a nervous twitch that made his nose quiver and his shoulder snap upward toward his cheek. I had never seen anyone do that and, finding it funny, bit my lip to suppress the impulse to laugh.

Although not as debonair as John Howell, during his stay in Great Britain, Michelagnoli had adopted a British demeanor. “The British say I look Italian. The Italians say I look British. If they could have agreed on this, they wouldn't be at war.”

Alfredo was more serious than most

confinati

, although at times he tried telling a joke or two with little success.

“You're still the professor at Oxford,” Mother remarked. “Now you are part of us. Our sense of humor is what keeps us going. Without it we would all go crazy.”

But Alfredo Michelagnoli, as long as I knew him, remained the pedantic Oxford professor.

I enjoyed the twice-a-week English lessons with the professor. Patient and skillful, in a short time taught me a working knowledge of English, enough to understand and respond when Jimmy Howell made one of his condescending remarks to me.

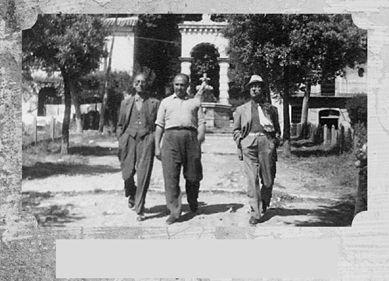

From left: William Pierce, Pietro Russo, Alfredo Michelagnoli with fountain in background in Ospedaletto, 1942.

Pietro Russo Is Freed

M

y mother's involvement with Pietro had become common knowledge among both the internees and the locals. I was getting annoyed that Pietro was now her favorite conversation topic. I couldn't understand why anyone would keep talking about one person so often and so much. Once, when Mother was in Dora's apartment, I put my ear against the door to listen. Again, she was babbling about Pietro, how much she loved, how she wanted nothing else but to spend the rest of her life with him, and on, and on. She also used many peculiar words I could not understand.

Without knocking, I stormed into the room. “I heard what you were saying. What about Papa? What's going to happen when Papa comes back to us?”

“I will have to deal with that,” Mamma answered.

“But I want to know!” I said loudly. “Is Papa going to be living with us, too?”

“I don't know.” Suddenly my mother had lost her self assurance.

Dora answered. “It will be all right, Enrico. I'm sure your mother will be able to make the right decision when your father comes back.”

I wanted an answer from my mother but got none. Dejected, I left the room and ran downstairs. My mind was in such turmoil. Pietro, Mamma, Papa, me. I did not know what I wanted to happen. I knew I wanted my father to come back to us. Of that I was sure. Or was I? I was happy being with Pietro, but did I want him to replace my father? Was Mother going to leave me to spend the rest of her life with this new man? I had heard of parents abandoning their children. Would I be roaming the streets without a parent or a place to live? Who would feed me? I could stay in Ospedaletto. Dora would take care of me. I may not go hungry but never again would I eat my favorite meal, Mother's

Wiener Schnitzel

!