A Cruel and Shocking Act: The Secret History of the Kennedy Assassination (20 page)

Read A Cruel and Shocking Act: The Secret History of the Kennedy Assassination Online

Authors: Philip Shenon

Slawson remembered a few early, nervous conversations among the lawyers about rumors that some rogue element of the CIA might be behind the assassination, or that President Johnson was involved. The conversations were “mostly humorous,” he said. Still, would the lawyers find their lives at risk if they unearthed a conspiracy within the U.S. government? Slawson remembered thinking that if he and his colleagues found evidence that the assassination was the result of some sort of coup d’état, they should expose it as quickly as possible, if only to keep themselves safe from an effort to silence them. “It was my theory that if you made it public, then they wouldn’t dare rub you out, because it would only solidify the evidence that it was true.”

On Monday, January 20, Warren called the first meeting of the staff. Years later, several lawyers remembered the excitement they felt to be in the presence of the chief justice, whose talents as a politician were still obvious. He charmed the young lawyers, speaking with “great warmth and sincerity,” Griffin recalled. According to memos of the meeting prepared by Willens and Eisenberg, the chief justice told the staff that their duty was “to determine the truth, whatever it might be.” He told them about his encounter with President Johnson in the Oval Office, and how Johnson had convinced him to take the job. The commission, Warren said, had a responsibility to put an end to the rumors that were sweeping the country—including rumors that Johnson himself had something to do with the murder. “The President stated that rumors of the most exaggerated kind were circulating in this country and overseas,” Warren said of his meeting with Johnson. “Some of those rumors could conceivably lead the country into a war which would cost 40 million lives.”

Warren offered a time line for the commission’s final report. It would be difficult to issue a report, he said, before the trial of Jack Ruby had been completed in Dallas; it was scheduled to begin in February. But Warren said he wanted to finish the report before the presidential campaign that fall “since once the campaign started it was very possible that rumors and speculation would gin up again.” He proposed a target date of June 1, less than five months away.

14

THE NEWSROOM OF THE

DALLAS MORNING NEWS

DALLAS, TEXAS

JANUARY 1964

Hugh Aynesworth of the

Dallas Morning News

was searching for a conspiracy, too. In the weeks after the assassination, no reporter in Texas had landed as many scoops about the president’s murder as Aynesworth, a thirty-two-year-old West Virginian who had been earning a paycheck as a newspaperman since he was a teenager. Over time, the Warren Commission would be forced to deal, repeatedly, with the aftermath of one of Aynesworth’s exclusives.

At first, Aynesworth said, he doubted Oswald could have carried out the assassination by himself. He guessed it was probably a conspiracy involving the Russians. His suspicion grew after he learned how Oswald had been permitted to leave the Soviet Union in 1962 and return home to the United States with his pretty young Russian wife. “I thought there was no way that this guy could get out of Russia with a Russian wife that fast,” he said. Aynesworth admitted that his suspicions were fueled by an assumption—felt nowhere more strongly than in ultraconservative Dallas—that the Kremlin’s leaders were evil enough to assassinate Kennedy. “We were all scared to death of the Russians.”

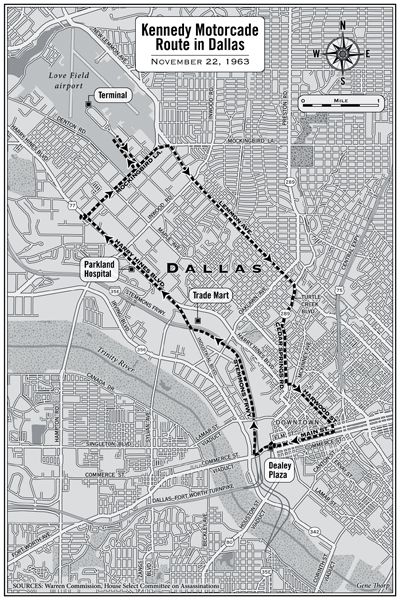

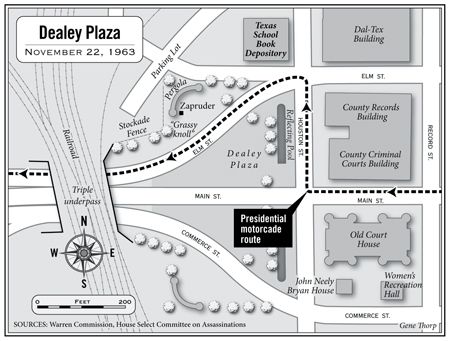

His competitors would have been loath to admit it, but Aynesworth was running circles around them on what would likely be the biggest story of their lives. He had managed to witness every major moment of the assassination drama, beginning on the day of the murder. He was in Dealey Plaza when the shots rang out; he had been inside the Texas Theatre when Oswald was captured and arrested later that afternoon; and he had been a few feet away from Oswald on Sunday morning in the basement of Dallas police headquarters when Ruby pushed through the crowd and killed him.

Aynesworth understood the risk that Kennedy had taken by visiting Dallas: the reporter felt the city deserved its reputation as a hateful place that was full of racists and right-wing extremists. Before the president’s trip, he assumed Kennedy might face some kind of ugly protest in the city. “I never dreamed they would shoot him, but I thought they would embarrass him by throwing something at him.”

Aynesworth was ashamed of his employer, a newspaper that he felt brought out the worst in its readers. In his view, the

News

fostered a spirit of intolerance in the city that might have helped inspire the assassination. “I felt badly because the editorial page of my newspaper had really caused it, as much as any other single thing,” Aynesworth said later. The paper’s “shrilly right-wing political slant appalled and embarrassed many people in the newsroom, including me.”

The paper was controlled by the radically conservative Dealey family—the small urban park where the president was shot was named for George Dealey, who bought the newspaper in 1926—and the

News

had criticized Kennedy mercilessly. In the fall of 1961, publisher Ted Dealey, George’s son, was among a group of Texas media executives invited to a meeting with Kennedy in the White House. Dealey used the opportunity to read a statement attacking the president to his face. “You and your administration are weak sisters,” he said. The nation needed “a man on horseback to lead the nation and many people in Texas and the Southwest think that you are riding Caroline’s tricycle.”

On the morning of the assassination, the paper had run a black-bordered, full-page advertisement placed by a group of right-wing extremists who identified themselves as the American Fact-Finding Committee. The ad accused Kennedy of allowing the Justice Department “to go soft on Communists, fellow travelers and ultra-leftists.” Jacqueline Kennedy remembered that, as they prepared to drive into Dallas in the motorcade, her husband showed her the ad and remarked, “We’re heading into nut country.”

Aynesworth had many gifts as a reporter, including a phenomenal memory, a polite, aw-shucks manner, and a slow, soft speaking style that encouraged people to trust him. Despite a boyish face, he was a big man who knew how to defend himself. He had a scar that ran from his throat to one ear, the result of an encounter with a knife-wielding assailant who broke into his home in Denver when he worked there as a reporter for United Press International. An admiring Texas reporter once said that the scar made Aynesworth “look like a cross between Andy Hardy and Al Capone.”

On the day of the assassination Aynesworth was not supposed to be in Dealey Plaza. He was the paper’s aviation and space correspondent—seen as the most prestigious reporting job on the paper, given the proximity of the new NASA space center in Houston—and originally he had no part in covering the president’s visit. He went to the plaza as a spectator, excited to see Kennedy and his glamorous wife. The moment shots rang out, however, he found himself in the middle of the mayhem. He immediately went to work. “My God, this is really happening,” he said to himself.

He had no notepad, so he grabbed a utility bill from his back pocket. He had no pen either, so he paid a child on the street 50 cents for his “fat jumbo pencil, like the ones kids used to use in early grade school.” A tiny plastic American flag dangled from the eraser.

“I was a reporter and I knew to start interviewing people,” Aynesworth said. And it was clear from the first minutes that the shots—he distinctly heard three of them—had probably been fired from the Texas School Book Depository. “I remember three or four people pointing toward the upper floors of the Book Depository.”

He saw police gathering around a frightened man on the street outside the book warehouse and overheard the man offer what appeared to be an eyewitness description of the assassin. The witness—Howard Brennan, a forty-four-year-old steamfitter who was still carrying his helmet from work—was telling the police officers that he had been across the street from the depository when he saw a man with a rifle lean from the window of one of the upper floors of the building. “I knew he was scared to death,” Aynesworth said of Brennan, who had noticed that reporters were listening in on the conversation, which made him even more upset. “He asked the police to get rid of us.”

About forty-five minutes after the assassination, Aynesworth heard a police radio crackle with a bulletin that a policeman, Officer J. D. Tippit, had been gunned down across town—in the Oak Cliff neighborhood of Dallas. Aynesworth sensed, instantly, that the shooting must be connected to the assassination, so he jumped in a car and rushed to Oak Cliff, where he found several people who said they had witnessed Tippit’s murder.

Helen Markham, a forty-seven-year-old waitress at the nearby Eatwell restaurant, had seen the killer—she later identified Oswald in a police lineup—pull a gun on Tippit and shoot him as the officer stepped from his squad car. “Strangest thing,” Aynesworth quoted her as saying of Oswald. “He didn’t run. He didn’t seem upset or scared. He just fooled with the gun and stared at me.” Then, Markham said, Oswald jogged away.

Several minutes later, Aynesworth followed police when they entered the nearby Texas Theatre, which was in the middle of a matinee showing of the film

War Is Hell

. Witnesses had reported a man resembling Oswald darting into the theater without buying a ticket. Aynesworth watched as the police entered the theater, turned up the lights, and grabbed Oswald, who initially resisted the arrest and pulled a pistol from his hip. After a scuffle, Oswald was taken into custody, yelling out, “I protest this police brutality.”

Aynesworth woke up on Sunday, November 24, to hear the news on television that Oswald would be transferred within minutes to the county jail. He rushed from the house without shaving or eating breakfast, arriving just in time at Dallas police headquarters. He was about fifteen feet away when Jack Ruby pushed through the crowd and shot Oswald in the stomach.

Aynesworth knew—and disliked—Ruby, a self-promoting strip-club operator who was always trying to befriend police officers (in hopes of protection) and reporters (in hopes of publicity). “He was a nut,” Aynesworth said. “Ruby was a showboat—always trying to get his picture in the papers, pictures of the strippers.” At the

News

, he was considered a “noxious presence” and a “loser.” Aynesworth recalled how, in the newspaper’s cafeteria, Ruby would “cut a peephole in his paper to keep up his surveillance as he pretended to read”—surveillance of what, it was never clear. Ruby was notoriously violent and always carried a gun. “I saw him twice beat up on drunks,” Aynesworth said. Ruby’s Carousel Club had a steep set of stairs that he turned into another weapon. “I remember him beating up this one guy and throwing him down the stairs, hurting the guy bad.”

Aynesworth was horrified by Oswald’s murder, but he was not surprised that Ruby was the killer. “If I had to pick out the one guy in all of Dallas, Texas, who would do something like this, I would think Ruby would be on the top of the list.”

*

Within hours of Kennedy’s assassination, Aynesworth started hearing from strangers who claimed they had secret information about a conspiracy to kill the president. He had encountered such people before on the space beat—“loonies, tin-foil people”—but never more than two or three a year. Now, “I was inundated with them.” The first, he said, showed up on the night of the assassination at his home—“an odd, bedraggled little man sitting on my doorstep.” The man was delusional and claimed the conspiracy involved an unlikely alliance of H. L. Hunt, the right-wing Dallas billionaire, and the Soviet Union. The second showed up the next morning, “a tall, painfully thin man who stank something awful” who managed to get into the newsroom. “I’ve got the story for you,” he told Aynesworth, claiming he knew the secret behind Kennedy’s murder. The man rolled up his trouser leg to reveal a huge abscess, which he claimed was somehow related to the conspiracy. “That’s how my leg got torn up.”

Over time, Aynesworth saw the conspiracy theorists fall into two categories. There were those who hoped to cash in on the murder by selling a wild story. “That makes money,” Aynesworth said. “Nobody pays for the truth. They pay for a conspiracy.” And there were others who wanted to enjoy, or at least embrace, the fantasy that they had played some part in this terrible drama. In that category he placed Carroll Jarnagin, a Dallas lawyer who claimed he had seen Oswald and Jack Ruby together in deep conversation in the Carousel Club days before the assassination. Aynesworth remembered Jarnagin, who was probably in his midforties, as a “bad alcoholic who always wanted to be somebody.… He just wanted attention.” The newspaperman knew better than to pay attention to Jarnagin, who also told his story about Oswald to the Dallas police. Later Jarnagin took a police polygraph examination about his claims and “failed miserably,” Aynesworth said.