A Cruel and Shocking Act: The Secret History of the Kennedy Assassination (74 page)

Read A Cruel and Shocking Act: The Secret History of the Kennedy Assassination Online

Authors: Philip Shenon

“I guess they will have to be sent out without his signature,” Eide wrote to Rankin, hinting that she knew just how close the commission had come to a divided report because of Russell. “And what’s the difference?” she wrote. “It didn’t seem to me that he did anything except cause us some trouble, so perhaps the books don’t deserve his ‘John Henry.’”

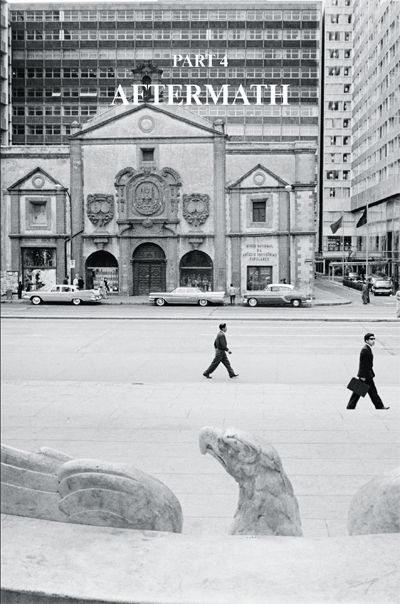

View from the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City, 1964

Almost immediately after the Warren Commission released its report in September 1964, information began to appear in classified government files that suggested that the history of the assassination would need to be rewritten. Most of that information would remain secret for decades. But in the swirl of unanswered questions about the president’s murder, the conspiracy movement would grow stronger in the 1960s, quickly convincing a majority of Americans that Lee Harvey Oswald had not acted alone. The commission’s legacy would come under harsh criticism from critics who would, over time, include some of the men who wrote the commission’s report.

55

OCTOBER 1964 THROUGH 1965

There was relief—delight, even—at the CIA in the days after the release of the Warren report. The fear that the CIA would be accused of bungling its supposedly aggressive surveillance of Oswald in Mexico a year earlier—that the agency might somehow have prevented the assassination—had been misplaced. The outcome was a credit, the agency thought, to Mexico City station chief Win Scott, who had taken such a personal role in convincing the commission that the CIA had done its job properly.

In a cable to the Mexico City station on September 25, the day after the commission’s report was presented to President Johnson, CIA headquarters offered its congratulations and thanks to Scott: “All Headquarters components involved in the OSWALD affair wish to express their appreciation to the Station for its effort in this and other facets of the OSWALD case.” The name of Scott’s old friend James Angleton, who had quietly controlled what information was shared with the commission, was not on the congratulatory cable from Langley. That would have been entirely in character for Angleton, who seemed to prefer always to lurk in the shadows, even within the hallways of the CIA itself.

So after all the good news from Washington and the pats on the back from his friends at Langley, the report that landed on Scott’s desk just two weeks later must have come as a surprise.

Dated October 5, it was from a CIA informant whose information, if true, meant that Scott and his colleagues—and through them, the Warren Commission—had never known the full story about Oswald’s trip to Mexico City. The informant, June Cobb, an American woman living in Mexico, had a complicated background. A Spanish-language translator, the Oklahoma-born Cobb had lived in Cuba earlier in the 1960s and had actually worked in Castro’s government; she was apparently sympathetic at the time to the Cuban revolution. Now in Mexico City, she was renting a room in the home of Elena Garro de Paz, the Mexican writer whose fame had grown with the 1963 publication of her much praised novel

Los Recuerdos del Porvenir

(

Recollections of Things to Come

). Scott knew the talented, opinionated Garro from the diplomatic party circuit.

Cobb described listening in on a conversation among Garro, her twenty-five-year-old daughter, Helena, and Elena’s sister, Deva Guerrero, that was prompted by the news from Washington about the just-released Warren Commission report. The three Mexican women told a remarkable story: they recalled how they had all encountered Oswald and his two “beatnik-looking” American friends at a dance party thrown by Silvia Duran’s family in September 1963, just weeks before the assassination. The Garros were cousins, by marriage, of Duran.

When Elena and her daughter “began asking questions about the Americans, who were standing together all evening and did not dance at all, they were shifted to another room,” Cobb reported. Elena said she continued to ask about the Americans and was told by Silvia’s husband that he “did not know who they were,” except that Silvia had brought them. When Elena pressed again to meet the Americans, she was told there was no time for an introduction. “The Durans replied that the boys were leaving town very early the next morning,” according to Cobb. They did not depart the city so quickly, as it turned out; Elena and her daughter saw the young Americans the next day walking together along a major Mexico City thoroughfare called Insurgentes.

The three women then described their astonishment when they saw photographs of Oswald in Mexican newspapers and on television in the hours after Kennedy’s assassination; they instantly remembered him from the “twist party.” The next day, they learned that Duran and her husband, Horacio, had been taken into custody by the Mexican police; the arrests “underlined” their certainty that it had been Oswald at the party. According to Cobb, Elena said she did not report any of her information about Oswald to the police out of fear that she and her daughter might be arrested, too. They did act immediately to distance themselves from the Durans, however. The Garros were “so sickened” at the thought that Silvia Duran and her family might have had some sort of connection to the president’s assassin that “they broke off their relations with the Durans.”

*

Scott might have hoped that the release of the Warren Commission meant he had put the questions about Oswald—and the threat they had once seemed to pose to Scott’s career—behind him. But given the potentially explosive information from June Cobb, he knew the embassy had to follow up. The job was given to FBI legal attaché Clark Anderson. He was the same FBI agent who, in the immediate aftermath of Kennedy’s assassination, had been in charge of the local investigation of Oswald’s activities in Mexico. If anyone should have tracked down the Garros earlier, it was Anderson.

The story that the Garros told Anderson was consistent, down to small details, with the account that Cobb had overheard. Elena Garro said she thought the party had taken place on Monday, September 30, 1963, or on one of the two following days: Tuesday, October 1, or Wednesday, October 2; she recalled thinking how unusual it was to have a dance party on a weekday. There had been about thirty people at the party, which was held at the home of Ruben Duran, Silvia’s brother-in-law. It was at about ten thirty p.m., she said, that “three young, white Americans arrived at the party. They were greeted by Silvia Duran and spoke only to her. They more or less isolated themselves from the rest of the party and, insofar as she observed, they had no conversation with anyone else.” Garro said the Americans “appeared to be between 22 and 24 years of age.” (Oswald was twenty-three at the time.) Oswald, she said, was dressed in a black sweater and appeared to be about five foot nine inches in height. (That was exactly Oswald’s height.) One of his two American companions was “about six feet tall, had blond, straight hair, a long chin, and was a bit ‘beatnik’ in appearance.” Anderson asked Garro if she recalled anyone else at the party. She did: a young Mexican who had flirted with her daughter. The man was contacted by the FBI and confirmed some elements of the Garros’ story, although he insisted he saw no one who looked like Oswald.

Anderson sent his report to Washington on December 11 and, his files suggest, did nothing more. There was no recorded effort to contact Garro’s sister, who had also been at the party. Anderson drew no final conclusion in the report but suggested that the Garros were simply mistaken about seeing Oswald. It was a judgment based largely on the fact that Oswald would not have been in Mexico City on two of the three possible dates offered by Elena Garro for the party, assuming that he was also seen on the street the next day. “It is noted that investigation has established that Lee Harvey Oswald departed Mexico City by bus at 8:30 a.m. on Oct. 2, 1963, and could not have been identical with the American allegedly observed by Mrs. Paz at the party if this party were held on the evening of Oct. 1 or Oct. 2,” Anderson reported. He did not point out the obvious: that on the first date offered by Garro, September 30, Oswald was in Mexico City and could have been seen on the street the next day.

It was not clear from Scott’s files that he notified CIA headquarters about any of this at the time. A later internal CIA chronology of the actions of the CIA Mexico City station suggested that none of the material reached Langley in 1964. If true, that would mean that CIA headquarters would learn nothing about the Garros—and the “twist party”—for another year.

*

As always, it seemed, Wesley Liebeler could not resist making trouble.

In the summer of 1965, he had agreed to meet a Cornell University graduate student, Edward Jay Epstein, who wanted to interview him about the Warren Commission. The thirty-year-old Epstein was writing a master’s thesis in government, using the commission as a case study in answering a question posed by one of his professors: “How does a government organization function in an extraordinary situation in which there are no rules or precedents to guide it?” Liebeler invited Epstein up to his vacation home in Vermont, where he had always found it easier to think.

In the ten months since the release of the commission’s report, Liebeler, now thirty-four, had made many changes in his life. Instead of resuming his promising career at a Manhattan law firm, he had moved west, accepting an appointment to teach law at the University of California at Los Angeles, specializing in antitrust law. The Southern California lifestyle was enticing to Liebeler, as were all the pretty young women on campus.

Liebeler was intrigued by Epstein’s Ivy League credentials. Here was a scholar, not a scandal-mongering reporter, and Liebeler thought Epstein’s research might help blunt the army of conspiracy theorists who were continuing to attack the commission’s findings. Several new books promoting conspiracy theories in Kennedy’s death, including one by Mark Lane, were in the works. Liebeler knew he was not alone in talking to Epstein, who also requested interviews with the seven commissioners. The young graduate student eventually talked to five of them—all except Warren, who declined, and Senator Russell, who was forced to cancel an interview because of illness. Epstein also interviewed Lee Rankin, Norman Redlich, and Howard Willens.

Liebeler told Epstein that, although he stood by the conclusions of the commission’s report, he was critical of the investigation. His comments were characteristically pithy—and indiscreet—and he would be quoted by name throughout Epstein’s thesis. Liebeler explained how the commission’s staff lawyers had done virtually all of the real detective work. Asked by Epstein how much work was done by the seven commissioners, Liebeler replied: “In one word, nothing.” (He would later say he did not recall making the comment to Epstein, although he did not dispute its accuracy.) Epstein would later recall how—in comments that were not published in his thesis—Liebeler “ridiculed the seven commissioners, saying the staff called them ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’ because of their refusal to question the claims of Oswald’s Russian wife, Marina, who was ‘Snow White.’” Liebeler had a slightly different roster than some of his colleagues in identifying which dwarf was which. He thought that “‘Dopey’ was Warren, who dismissed any testimony that impugned Marina’s credibility,” while “Sleepy” was Allen Dulles “because he often fell asleep during the testimony of witnesses and, when awakened, asked inappropriate questions.” John McCloy was “Grumpy” because “he became angry when staff lawyers did not pay sufficient attention to his theories about possible foreign involvement.”

Liebeler revealed the intense time constraints faced by the staff, a situation made worse by the FBI’s incompetence; he described the bureau’s investigation of the assassination as “a joke.” He told Epstein about Rankin’s ill-chosen comment at the end of the investigation regarding the need to draw the work to a close, even if there were still unanswered questions: “We are supposed to be closing doors, not opening them.” That quotation, when published by Epstein, would be cited regularly by conspiracy theorists as proof that the investigation had been rushed to a preordained conclusion.

*

Liebeler went one step further to help Epstein: he turned over copies of most, if not all, of the internal files he had taken from the commission, including the memos he had written to protest that the report was being written as a “brief for the prosecution” against Oswald. In his thesis, a grateful Epstein did not identify Liebeler by name as the source of the files, offering thanks only to an unnamed “member of the staff.” Years later, Epstein would recall his excitement when Liebeler agreed to give him two large cardboard boxes crammed with “staff reports, draft chapters … and two blue-bound volumes of preliminary FBI reports, which had not been released to the public.”

Liebeler told friends that he did not foresee what was about to happen. Epstein, it turned out, had found a respected publisher, Viking Press, to turn his thesis into a book,

Inquest: The Warren Commission and the Establishment of Truth

, with publication set for June 1966, just two months after he submitted his thesis to his advisers at Cornell. The publication date meant that his book would reach bookstores ahead of Lane’s

Rush to Judgment

, which was scheduled for release later that summer. Before publication, Epstein was coy about what would be in

Inquest

, telling the

New York Times

, “It may be dull—let’s wait and see.” Reviewers were intrigued that the book’s introduction would be written by Richard Rovere, the Washington correspondent for the

New Yorker

. Whatever was in the book, it would apparently be a serious work.