A Guide to the Odyssey: A Commentary on the English Translation of Robert Fitzgerald (12 page)

Read A Guide to the Odyssey: A Commentary on the English Translation of Robert Fitzgerald Online

Authors: Ralph J. Hexter,Robert Fitzgerald

Tags: #Homer, #Language Arts & Disciplines, #Greek Language - Translating Into English, #Greek Language, #Fitzgerald; Robert - Knowledge - Language and Languages, #History and Criticism, #Epic Poetry; Greek - History and Criticism, #Poetry, #Odysseus (Greek Mythology) in Literature, #Literary Criticism, #Translating & Interpreting, #Ancient & Classical, #Translating Into English, #Epic Poetry; Greek

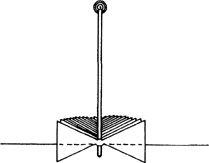

6. A fifth-century coin from Thebes shows how an archer is to string the double-torsion bow. Whether sitting (like Odysseus) or crouching (as here), one pushes the bow against the heel of the foot planted behind on the ground. Only in that way can one muster sufficient force to bend the composite bow far enough to get the string around the upper end.

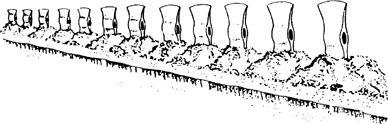

7. This is one possible arrangement of the axe heads through which Odysseus sends his prize-winning shot. Debate continues about the precise arrangement Homer intended us to imagine (see the note on XXI. 132–37). One solution, depicted above, envisages Minoan/Mycenaean cult axes with rings at the bases of their handles by which they could be hung up and displayed. In this case, the prize shot would pass through the series of rings at the top of the inverted axes.

8. A second argument has the axe heads fixed in the ground. The challenge is to shoot through the series of holes in the axe heads into which handles would normally be fitted. This is the image that Fitzgerald presents in his translation (“iron axe-helve sockets,” XXI.80, and “socket ring(s),” XXI.137 and 483). Visible is the earthen ridge that Telémakhos forms “to hold the blades half-bedded” (XII. 134–35). In either case a successful archer would have to be seated, as Odysseus is (XXI.480).

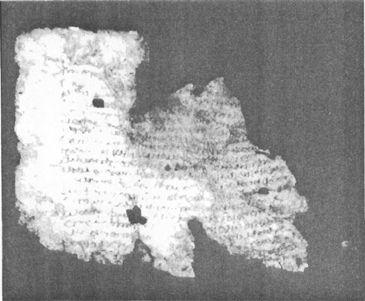

9. This fragment from an early vellum book of the late third or fourth century

C.E

. displays

Book XV

. 189–210 of

The Odyssey

(corresponding to XV.235–60 in Fitzgerald’s translation; on its back are XV.161–81, XV. 198–225 in English). Since the oldest extant complete manuscript of the epic dates from the tenth or eleventh century, earlier fragments can give us insight into the history of the text. This fragment exhibits the standardized or vulgate text that was well established by ca. 150

B.C.E

. Greco-Roman booksellers, like their later cousins, wished to purvey the most authoritative and popular text.

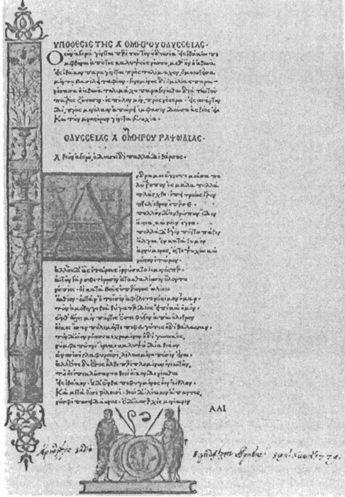

10. A page from the

Editio princeps

(1488), the first printed edition of

The Odyssey

(the original is 12¾ inches high). The Greek text (lines I.1–32 in Fitzgerald’s translation) begins with the large initial alpha—the

A

of

andra

, man—which a calligrapher filled in after the book was printed. This artist also decorated the left and lower margins and inscribed the capital O at the top of the page that begins the

hypothesis:

a summary of

Book I

of

The Odyssey

. Calligraphic initial capitals (majuscules) were among the features of medieval manuscripts preserved in the earliest printed books.

A Goddess Intervenes

1

Sing in me, Muse:

The poet asks the collective cultural memory to sing through him, even breathe into him [

ennepe

, 1]. The Muse, or Muses (on the number of Muses, see XXIV.68, below) are the daughters of Zeus (see I.17, or

Iliad II

.491). Hesiod, Homer’s near contemporary—chronological certainty is not possible, but Hesiod (c. 700

B.C.E

.) clearly knew the Homeric poems and can thus be placed later than Homer—names Mnemosyne, “Memory,” as the mother (

Theogony

54). Such divine genealogies provided Greek thinkers a way of expressing the close connections of ideas and attributes. (For a mortal example, see I.142ff., below.) The Muse guarantees that what the bard relates is true memory (on “Memory” and epic, see Introduction, p. lxvi).

For a comparison of this prologue or proem and that of

The Iliad

, with which it has much in common, see West (HWH I.67–69).

2

skilled in all ways of contending

represents one of the most important epithets of Odysseus, in Greek

polytropos

[1], which means “versatile,” “with many twists and turns.” This is the first of a veritable family of

poly-

epithets, bound together in the Greek by the shared first element,

poly-

, “many-.” Though English has a few such phrases (“many-splendored”), Fitzgerald rightly does not attempt to create a comparably recognizable series in his translation, preferring variety and above all what seems to fit best in the immediate context. When

polytropos

appears next, it is as “O great contender” (X.371 [330]).

The most frequent

poly-

epithets for Odysseus are

polytlas

, “much enduring” (Fitzgerald’s “For all he had endured,” V.181 [171]),

polymêkhanos

, “much conniving” (“versatile,” V.212 [203]), and

polymêtis

, “with many wiles” (“the strategist,” V.223 [214]; see also XIX.65, below). Both aspects—Odysseus’ creative cunning and his manifold misfortunes—are reflected in the less frequent

poly-

compounds connected with him. Both his nurse (“in his craftiness,” XXIII.85 [

polyïdriêisi

, 77]) and one of the suitors (XXIV. 187 [

polykerdeiêisin

, 167]) highlight his wiliness, as does the narrator (XIII.324–25 [

polykerdea

, 255]). Athena will shortly refer to him as “wise” (I.108 [

polyphrona

, 83]).

Odysseus is made to use

poly-

compounds when he refers to his suffering: twice he refers to his

polykêdea noston

, “homeward journey involving pains of all sorts” (to the Phaiákians, IX.41–43

[37], to Penélopê, XXIII.398–99 [351]) and yet another

poly-compound

is behind the words “My heart is sore” that Odysseus, now disguised as a wayfaring Kretan noble, utters to Penélopê (XIX. 141 [

polystonos

, 118]). Another member of this

poly-

system is the octopus to which Odysseus is compared (see V.451, below).

Flexibility, adaptability, and trickiness belong to the core of Odysseus’ being, as

The Odyssey

shows at every turn (see, for example, XXIII. 149–58, below). The first time the narrator (as opposed to a speaker) mentions Odysseus in

The Iliad

, it is with the epithet

polymêtis (Iliad I

.311). On the all-important characteristic of mêtis, “cunning intelligence,” see IX.394, XX.21, and XXIII. 142, below; also M. Detienne and J.-P. Vernant,

Cunning Intelligence in Greek Culture and Society

(cited in the Bibliography, below).

4–5

after he plundered … Troy:

Odysseus, in large measure thanks to his wiliness—the ruse of Trojan horse was his idea (see VIII.84–85, below)—was indeed the key to Greek victory. While not the equal of Akhilleus or Aias in pure killing power, he was a formidable soldier. However, no one could equal him in those qualities which are as valuable at home and in peace as in combat: persuasion and strategy.

7

learned the minds of many distant men:

In fact, of many different

people [anthrôpôn

, 3]. On this aspect of Odysseus’ character, see IX.184ff. and XII. 193, below.

10–12

shipmates

…: None of Odysseus’ shipmates [

hetairoi

] will return. In the proem, Homer emphasizes Odysseus’ attempts to save them from their own folly, especially marked in the episode highlighted here (13–16) when they killed and ate of the sun god’s sacred cattle (XII.339–555). But many were already lost in other gruesome ways (so claims Odysseus’ narrative that begins in

Book IX

). In fact, Eurýlokhos accuses Odysseus of having caused the deaths of some by just the sort of “recklessness” described here (“foolishness,” X.484). On Vergil’s implicit critique of Odysseus’ irresponsibility, see Introduction, p. xx.

13

children and fools:

One word in Greek [

nêpioi

, 8], and entirely negative in connotation here (see also XIII. 300–317, below: “great booby,” XIII.302). For a striking instance of cultural transvaluation, contrast a considerably later Greek writer’s use of the same word: St. Paul’s “babes in Christ” (I Cor. 3.1). Long before Paul, Greek writers were marking their distance from Homer by employing words familiar from his texts—for Homer was the staple of Greek education for more than a millennium—in new ways.

13, 39–41

Homeric figures, both gods and humans, take pleasure in feasting, which is one of the central images of the poem as it was a central institution of Homeric society. The feast is a social event, ideally a symbol of harmony, not only among humans but, if the sacrificial ceremonies have been properly observed, between gods and men. However, like all rites, it can be perverted. The theme of eating is remarkably prominent in

The Odyssey

, both good (the meal in Eumaios’ hut), and more frequently bad (e.g., monstrous cannibalism, Odysseus’ crew’s eating of Hêlios’ herd, and the suitors’ gorging themselves in Odysseus’ home on his substance).

16

The dawn of their return:

The translator waxes slightly poetic to mark the end of his verse paragraph. Homer merely says, “he [

Hêlios

] took away the day of their homecoming” [9]. Which is not to say that Homer is unpoetic, and surely not as prosaic as my literal translation might suggest. He achieves his effects over the longer stretches, that the rhythmic roll of dactylic hexameters makes possible.

17

Muse, Daughter of Zeus:

See 1, above.

18

us:

Not just the poet but the audience as well.

19

Begin:

On the issue of starting points and narrative order, traditional in epic proems, see IX. 14–15, below.