A Man Without a Country (5 page)

Read A Man Without a Country Online

Authors: Kurt Vonnegut

Tags: #History, #General, #United States, #Humor, #20th century, #Literary, #American, #Biography, #Political Science, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Authors; American, #Authors; American - 20th century, #Literary Criticism, #Literary Collections, #Form, #Essays, #Political Process, #United States - Politics and government - 2001, #Vonnegut; Kurt, #United States - Politics and government - 2001-2009

I turned eighty-two on November

11, 2004. What’s it like to be this old? I can’t parallel park worth a damn anymore, so please don’t watch while I try to do it. And gravity has become a lot less friendly and manageable than it used to be.

When you get to my age, if you get to my age, and if you have reproduced, you will find yourself asking your own children, who are themselves middle-aged, “What is life all about?” I have seven kids, three of them orphaned nephews.

I put my big question about life to my son the pediatrician. Dr. Vonnegut said this to his doddering old dad: “Father, we are here to help each other get through this thing, whatever it is.”

No matter how

corrupt, greedy, and heartless our government, our corporations, our media, and our religious and charitable institutions may become, the music will still be wonderful.

If I should ever die, God forbid, let this be my epitaph:

THE ONLY PROOF HE NEEDED FOR THE EXISTENCE OF GOD WAS MUSIC

Now, during our catastrophically idiotic war in Vietnam, the music kept getting better and better and better. We lost that war, by the way. Order couldn’t be restored in Indochina until the people kicked us out.

That war only made billionaires out of millionaires. Today’s war is making trillionaires out of billionaires. Now I call that progress.

And how come the people in countries we invade can’t fight like ladies and gentlemen, in uniform and with tanks and helicopter gunships?

Back to music. It makes practically everybody fonder of life than he or she would be without it. Even military bands, although I am a pacifist, always cheer me up. And I really like Strauss and Mozart and all that, but the priceless gift that African Americans gave the whole world when they were still in slavery was a gift so great that it is now almost the only reason many foreigners still like us at least a little bit. That specific remedy for the worldwide epidemic of depression is a gift called the blues. All pop music today—jazz, swing, be-bop, Elvis Presley, the Beatles, the Stones, rock-and-roll, hip-hop, and on and on—is derived from the blues.

A gift to the world? One of the best rhythm-and-blues combos I ever heard was three guys and a girl from Finland playing in a club in Krakow, Poland.

The wonderful writer Albert Murray, who is a jazz historian and a friend of mine among other things, told me that during the era of slavery in this country—an atrocity from which we can never fully recover—the suicide rate per capita among slave owners was much higher than the suicide rate among slaves.

Murray says he thinks this was because slaves had a way of dealing with depression, which their white owners did not: They could shoo away Old Man Suicide by playing and singing the Blues. He says something else which also sounds right to me. He says the blues can’t drive depression clear out of a house, but can drive it into the corners of any room where it’s being played. So please remember that.

Foreigners love us for our jazz. And they don’t hate us for our purported liberty and justice for all. They hate us now for our arrogance.

When I went to

grade school in Indianapolis, the James Whitcomb Riley School #43, we used to draw pictures of houses of tomorrow, boats of tomorrow, airplanes of tomorrow, and there were all these dreams for the future. Of course at that time everything had come to a stop. The factories had stopped, the Great Depression was on, and the magic word was Prosperity. Sometime Prosperity will come. We were preparing for it. We were dreaming of the sorts of houses human beings should inhabit—ideal dwellings, ideal forms of transportation.

What is radically new today is that my daughter, Lily, who has just turned twenty-one, finds herself, as do your children, as does George W. Bush, himself a kid, and Saddam Hussein and on and on, heir to a shockingly recent history of human slavery, to an AIDS epidemic, and to nuclear submarines slumbering on the floors of fjords in Iceland and elsewhere, crews prepared at a moment’s notice to turn industrial quantities of men, women, and children into radioactive soot and bone meal by means of rockets and H-bomb warheads. Our children have inherited technologies whose byproducts, whether in war or peace, are rapidly destroying the whole planet as a breathable, drinkable system for supporting life of any kind.

Anyone who has studied science and talks to scientists notices that we are in terrible danger now. Human beings, past and present, have trashed the joint.

The biggest truth to face now—what is probably making me unfunny now for the remainder of my life—is that I don’t think people give a damn whether the planet goes on or not. It seems to me as if everyone is living as members of Alcoholics Anonymous do, day by day. And a few more days will be enough. I know of very few people who are dreaming of a world for their grandchildren.

Many years ago

I was so innocent I still considered it possible that we could become the humane and reasonable America so many members of my generation used to dream of. We dreamed of such an America during the Great Depression, when there were no jobs. And then we fought and often died for that dream during the Second World War, when there was no peace.

But I know now that there is not a chance in hell of America becoming humane and reasonable. Because power corrupts us, and absolute power corrupts us absolutely. Human beings are chimpanzees who get crazy drunk on power. By saying that our leaders are power-drunk chimpanzees, am I in danger of wrecking the morale of our soldiers fighting and dying in the Middle East? Their morale, like so many lifeless bodies, is already shot to pieces. They are being treated, as I never was, like toys a rich kid got for Christmas.

The most intelligent

and decent prayers ever uttered by a famous American, addressed To Whom It May Concern, and following an enormous man-made calamity, were those of Abraham Lincoln at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, back when battlefields were small. They could be seen in their entirety by men on horseback atop a hill. Cause and effect were simple. Cause was gunpowder, a mixture of potassium nitrate, charcoal, and sulfur. Effect was flying metal. Or a bayonet. Or a rifle butt.

Abraham Lincoln said this about the silenced killing grounds at Gettysburg:

We cannot dedicate—we cannot

consecrate—we cannot hallow this ground.

The brave men, living and dead, who

struggled here have consecrated it far above

our poor power to add or detract.

Poetry! It was still possible to make horror and grief in wartime seem almost beautiful. Americans could still have illusions of honor and dignity when they thought of war. The illusion of human you-know-what. That is what I call it: “The you-know-what.”

And may I note parenthetically that I have already in this section exceeded by a hundred words or more the whole of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. I am windy.

Killing industrial

quantities of defenseless human families, whether by old-fashioned apparatus or by newfangled contraptions from universities, in the expectation of gaining military or diplomatic advantage thereby, may not be such a hot idea after all.

Does it work?

Its enthusiasts, its fans, if I may call them that, assume that leaders of political entities we find inconvenient or worse are capable of pity for their own people. If they see or at least hear about fricasseed women and children and old people who looked and talked like themselves, maybe even relatives, they will be incapacitated by weepiness. So goes the theory, as I understand it.

Anyone who believes that might as well go all the way and make Santa Claus and the tooth fairy icons of our foreign policy.

Where are Mark Twain

and Abraham Lincoln now when we need them? They were country boys from Middle America, and both of them made the American people laugh at themselves and appreciate really important, really moral jokes. Imagine what they would have to say today.

One of the most humiliated and heartbroken pieces Mark Twain ever wrote was about the slaughter of six hundred Moro men, women, and children by our soldiers during our liberation of the people of the Philippines after the Spanish-American War. Our brave commander was Leonard Wood, who now has a fort named after him. Fort Leonard Wood in Missouri.

What did Abraham Lincoln have to say about America’s imperialist wars, the ones that, on one noble pretext or another, aim to increase the natural resources and pools of tame labor available to the richest Americans who have the best political connections?

It is almost always a mistake to mention Abraham Lincoln. He always steals the show. I am about to quote him again.

More than a decade before his Gettysburg Address, back in 1848, when Lincoln was only a Congressman, he was heartbroken and humiliated by our war on Mexico, which had never attacked us. James Polk was the person Representative Lincoln had in mind when he said what he said. Abraham Lincoln said of Polk, his president, his armed forces’ commander-in-chief:

Trusting to escape scrutiny, by fixing the public gaze upon the exceeding brightness of military glory—that attractive rainbow, that rises in showers of blood—that serpent’s eye, that charms to destroy—he plunged into war.

Holy shit! And I thought I was a writer!

Do you know we actually captured Mexico City during the Mexican War? Why isn’t that a national holiday? And why isn’t the face of James Polk, then our president, up on Mount Rushmore along with Ronald Reagan’s? What made Mexico so evil back in the 1840s, well before our Civil War, is that slavery was illegal there. Remember the Alamo? With that war we were making California our own, and a lot of other people and properties, and doing it as though butchering Mexican soldiers who were only defending their homeland against invaders wasn’t murder. What other stuff besides California? Well, Texas, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, and parts of New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming.

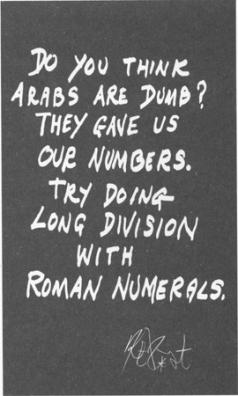

Speaking of plunging into war, do you know why I think George W. Bush is so pissed off at Arabs? They brought us algebra. Also the numbers we use, including a symbol for nothing, which Europeans had never had before. You think Arabs are dumb? Try doing long division with Roman numerals.

Do you know what a humanist is?

My parents and grandparents were humanists, what used to be called Free Thinkers. So as a humanist I am honoring my ancestors, which the Bible says is a good thing to do. We humanists try to behave as decently, as fairly, and as honorably as we can without any expectation of rewards or punishments in an afterlife. My brother and sister didn’t think there was one, my parents and grandparents didn’t think there was one. It was enough that they were alive. We humanists serve as best we can the only abstraction with which we have any real familiarity, which is our community.

I am, incidentally, Honorary President of the American Humanist Association, having succeeded the late, great science fiction writer Isaac Asimov in that totally functionless capacity. We had a memorial service for Isaac a few years back, and I spoke and said at one point, “Isaac is up in heaven now.” It was the funniest thing I could have said to an audience of humanists. I rolled them in the aisles. It was several minutes before order could be restored. And if I should ever die, God forbid, I hope you will say, “Kurt is up in heaven now.” That’s my favorite joke.

How do humanists feel about Jesus? I say of Jesus, as all humanists do, “If what he said is good, and so much of it is absolutely beautiful, what does it matter if he was God or not?”

But if Christ hadn’t delivered the Sermon on the Mount, with its message of mercy and pity, I wouldn’t want to be a human being.

I’d just as soon be a rattlesnake.

Human beings

have had to guess about almost everything for the past million years or so. The leading characters in our history books have been our most enthralling, and sometimes our most terrifying, guessers.

May I name two of them?

Aristotle and Hitler.

One good guesser and one bad one.

And the masses of humanity through the ages, feeling inadequately educated just like we do now, and rightly so, have had little choice but to believe this guesser or that one.

Russians who didn’t think much of the guesses of Ivan the Terrible, for example, were likely to have their hats nailed to their heads.

We must acknowledge that persuasive guessers, even Ivan the Terrible, now a hero in the Soviet Union, have sometimes given us the courage to endure extraordinary ordeals which we had no way of understanding. Crop failures, plagues, eruptions of volcanoes, babies being born dead—the guessers often gave us the illusion that bad luck and good luck were understandable and could somehow be dealt with intelligently and effectively. Without that illusion, we all might have surrendered long ago.

But the guessers, in fact, knew no more than the common people and sometimes less, even when, or especially when, they gave us the illusion that we were in control of our destinies.

Persuasive guessing has been at the core of leadership for so long, for all of human experience so far, that it is wholly unsurprising that most of the leaders of this planet, in spite of all the information that is suddenly ours, want the guessing to go on. It is now their turn to guess and guess and be listened to. Some of the loudest, most proudly ignorant guessing in the world is going on in Washington today. Our leaders are sick of all the solid information that has been dumped on humanity by research and scholarship and investigative reporting. They think that the whole country is sick of it, and they could be right. It isn’t the gold standard that they want to put us back on. They want something even more basic. They want to put us back on the snake-oil standard.

Loaded pistols are good for everyone except inmates in prisons or lunatic asylums.

That’s correct.

Millions spent on public health are inflationary.

That’s correct.

Billions spent on weapons will bring inflation down.

That’s correct.

Dictatorships to the right are much closer to American ideals than dictatorships to the left.

That’s correct.

The more hydrogen bomb warheads we have, all set to go off at a moment’s notice, the safer humanity is and the better off the world will be that our grandchildren will inherit.

That’s correct.

Industrial wastes, and especially those that are radioactive, hardly ever hurt anybody, so everybody should shut up about them.

That’s correct.

Industries should be allowed to do whatever they want to do: Bribe, wreck the environment just a little, fix prices, screw dumb customers, put a stop to competition, and raid the Treasury when they go broke.

That’s correct.

That’s free enterprise.

And that’s correct.

The poor have done something very wrong or they wouldn’t be poor, so their children should pay the consequences.

That’s correct.

The United States of America cannot be expected to look after its own people.

That’s correct.

The free market will do that.

That’s correct.

The free market is an automatic system of justice.

That’s correct.

I’m kidding.

And if you actually are an educated, thinking person, you will not be welcome in Washington, D.C. I know a couple of bright seventh graders who would not be welcome in Washington, D.C. Do you remember those doctors a few months back who got together and announced that it was a simple, clear medical fact that we could not survive even a moderate attack by hydrogen bombs? They were not welcome in Washington, D.C.

Even if we fired the first salvo of hydrogen weapons and the enemy never fired back, the poisons released would probably kill the whole planet by and by.

What is the response in Washington? They guess otherwise. What good is an education? The boisterous guessers are still in charge—the haters of information. And the guessers are almost all highly educated people. Think of that. They have had to throw away their educations, even Harvard or Yale educations.

If they didn’t do that, there is no way their uninhibited guessing could go on and on and on. Please, don’t you do that. But if you make use of the vast fund of knowledge now available to educated persons, you are going to be lonesome as hell. The guessers outnumber you—and now I have to guess—about ten to one.

In case you

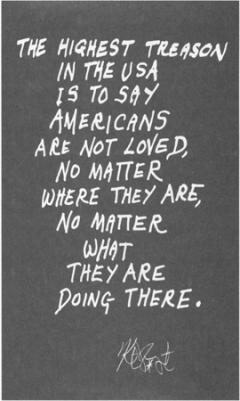

haven’t noticed, as the result of a shamelessly rigged election in Florida, in which thousands of African Americans were arbitrarily disenfranchised, we now present ourselves to the rest of the world as proud, grinning, jut-jawed, pitiless war-lovers with appallingly powerful weaponry—who stand unopposed.

In case you haven’t noticed, we are now as feared and hated all over the world as the Nazis once were.

And with good reason.

In case you haven’t noticed, our unelected leaders have dehumanized millions and millions of human beings simply because of their religion and race. We wound ’em and kill ’em and torture ’em and imprison ’em all we want.

Piece of cake.

In case you haven’t noticed, we also dehumanized our own soldiers, not because of their religion or race, but because of their low social class.

Send ’em anywhere. Make ’em do anything.

Piece of cake.

The O’Reilly Factor.

So I am a man without a country, except for the librarians and a Chicago paper called

In These Times

.

Before we attacked Iraq, the majestic

New York Times

guaranteed that there were weapons of mass destruction there.

Albert Einstein and Mark Twain gave up on the human race at the end of their lives, even though Twain hadn’t even seen the First World War. War is now a form of TV entertainment, and what made the First World War so particularly entertaining were two American inventions, barbed wire and the machine gun.

Shrapnel was invented by an Englishman of the same name. Don’t you wish you could have something named after you?

Like my distinct betters Einstein and Twain, I now give up on people, too. I am a veteran of the Second World War and I have to say this is not the first time I have surrendered to a pitiless war machine.

My last words? “Life is no way to treat an animal, not even a mouse.”

Napalm came from Harvard.

Veritas!

Our president is a Christian? So was Adolf Hitler.

What can be said to our young people, now that psychopathic personalities, which is to say persons without consciences, without senses of pity or shame, have taken all the money in the treasuries of our government and corporations, and made it all their own?

And the most

I can give you to cling to is a poor thing, actually. Not much better than nothing, and maybe it’s a little worse than nothing. It is the idea of a truly modern hero. It is the bare bones of the life of Ignaz Semmelweis, my hero.

Ignaz Semmelweis was born in Budapest in 1818. His life overlapped with that of my grandfather and with that of your grandfathers, and it may seem a long time ago, but actually he lived only yesterday.

He became an obstetrician, which should make him modern hero enough. He devoted his life to the health of babies and mothers. We could use more heroes like that. There’s damn little caring for mothers, babies, old people, or anybody physically or economically weak these days as we become ever more industrialized and militarized with the guessers in charge.

I have said to you how new all this information is. It is so new that the idea that many diseases are caused by germs is only about 140 years old. The house I own in Sagaponack, Long Island, is nearly twice that old. I don’t know how they lived long enough to finish it. I mean, the germ theory is really recent. When my father was a little boy, Louis Pasteur was still alive and still plenty controversial. There were still plenty of high-powered guessers who were furious at people who would listen to him instead of to them.

Yes, and Ignaz Semmelweis also believed that germs could cause diseases. He was horrified when he went to work for a maternity hospital in Vienna, Austria, to find out that one mother in ten was dying of childbed fever.

These were poor people—rich people still had their babies at home. Semmelweis observed hospital routines, and began to suspect that doctors were bringing the infection to the patients. He noticed that the doctors often went directly from dissecting corpses in the morgue to examining mothers in the maternity ward. He suggested as an experiment that the doctors wash their hands before touching the mothers.

What could be more insulting? How dare he make such a suggestion to his social superiors? He was a nobody, he realized. He was from out of town, with no friends and protectors among the Austrian nobility. But all that dying went on and on, and Semmelweis, having far less sense about how to get along with others in this world than you and I would have, kept on asking his colleagues to wash their hands.

They at last agreed to do this in a spirit of lampoonery, of satire, of scorn. How they must have lathered and lathered and scrubbed and scrubbed and cleaned under their fingernails.

The dying stopped—imagine that! The dying stopped. He saved all those lives.

Subsequently, it might be said that he has saved millions of lives—including, quite possibly, yours and mine. What thanks did Semmelweis get from the leaders of his profession in Viennese society, guessers all? He was forced out of the hospital and out of Austria itself, whose people he had served so well. He finished his career in a provincial hospital in Hungary. There he gave up on humanity—which is us, and our information-age knowledge—and on himself.

One day, in the dissecting room, he took the blade of a scalpel with which he had been cutting up a corpse, and he stuck it on purpose into the palm of his hand. He died, as he knew he would, of blood poisoning soon afterward.

The guessers had had all the power. They had won again. Germs indeed. The guessers revealed something else about themselves, too, which we should duly note today. They aren’t really interested in saving lives. What matters to them is being listened to—as, however ignorantly, their guessing goes on and on and on. If there’s anything they hate, it’s a wise human.

So be one anyway. Save our lives and your lives, too. Be honorable.