A Man Without a Country (7 page)

Read A Man Without a Country Online

Authors: Kurt Vonnegut

Tags: #History, #General, #United States, #Humor, #20th century, #Literary, #American, #Biography, #Political Science, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Authors; American, #Authors; American - 20th century, #Literary Criticism, #Literary Collections, #Form, #Essays, #Political Process, #United States - Politics and government - 2001, #Vonnegut; Kurt, #United States - Politics and government - 2001-2009

Now then, I have some good news for

you and some bad news. The bad news is that the Martians have landed in New York City and are staying at the Waldorf Astoria. The good news is that they only eat homeless men, women, and children of all colors, and they pee gasoline.

Put that pee in a Ferrari, and you can go a hundred miles an hour. Put some in an airplane, and you can go as fast as a bullet and drop all kinds of crap on Arabs. Put some in a school bus, and it’ll get the kids to and from school. Put some in a fire engine, and it will get firemen to the fire so they can put the fire out. Put some in a Honda, and it’ll get you to work and then back home again.

And wait until you hear what the Martians poop. It’s uranium. Just one of them can light and heat every home and school and church and business in Tacoma.

But seriously, if you keep up with current events in the supermarket tabloids, you know that a team of Martian anthropologists has been studying our culture for the past ten years, since our culture is the only one worth a nickel on the whole planet. You can sure forget Brazil and Argentina.

Anyway, they went home last week, because they knew how terrible global warming was about to become. Their space vehicle, incidentally, wasn’t a flying saucer. It was more like a flying soup tureen. And they’re little all right, only six inches high. But they are not green. They’re mauve.

And their little mauve leader, by way of farewell, said in that teeny-weeny, tanny-wanny, toney little voice of hers that there were two things about American culture no Martian would ever understand.

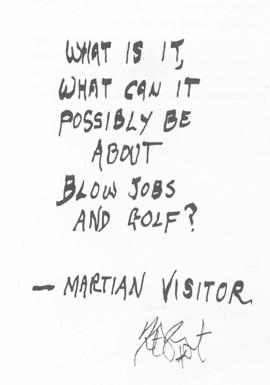

“What is it,” she squeaked, “what can it possibly be about blowjobs and golf?”

That is stuff from a novel I’ve been working on for the past five years, about Gil Berman, thirty-six years my junior, a standup comedian at the end of the world. It is about making jokes while we are killing all the fish in the ocean, and touching off the last chunks or drops or whiffs of fossil fuel. But it will not let itself be finished.

Its working title—or actually, its nonworking title—is

If God Were Alive Today

. And hey, listen, it is time we thanked God that we are in a country where even the poor people are overweight. But the Bush diet could change that.

And about the novel I can never finish,

If God Were Alive Today

, the hero, the stand-up comedian on Doomsday, not only does he denounce our addiction to fossil fuels and the pushers in the White House, because of overpopulation he is also against sexual intercourse. Gil Berman tells his audiences:

I have become a flaming neuter. I am as celibate as at least fifty percent of the heterosexual Roman Catholic clergy. And celibacy is no root canal. It’s so cheap and convenient. Talk about safe sex! You don’t have to do anything afterwards, because there is no afterward.

And when my tantrum, which is what I call my TV set, flashes boobs and smiles in my face, and says everybody but me is going to get laid tonight, and this is a national emergency, so I’ve got to rush out and buy a car or pills, or a folding gymnasium that I can hide under my bed, I laugh like a hyena. I know and you know that millions and millions of good Americans, present company not excepted, are not going to get laid tonight.

And we flaming neuters vote! I look forward to a day when the President of the United States, no less, who probably isn’t going to get laid tonight either, decrees a National Neuter Pride Day. Out of our closets we’ll come by the millions. Shoulders squared, chins held high, we’ll go marching up Main Streets all over this boob-crazed democracy of ours, laughing like hyenas.

What about God? If He were alive today? Gil Berman says, “God would have to be an atheist, because the excrement has hit the air-conditioning big time, big time.”

I think one

of the biggest mistakes we’re making, second only to being people, has to do with what time really is. We have all these instruments for slicing it up like a salami, clocks and calendars, and we name the slices as though we own them, and they can never change—“11:00

AM

, November 11, 1918,” for example—when in fact they are as likely to break into pieces or go scampering off as dollops of mercury.

Might not it be possible, then, that the Second World War was a cause of the first one? Otherwise, the first one remains inexplicable nonsense of the most gruesome kind. Or try this: Is it possible that seemingly incredible geniuses like Bach and Shakespeare and Einstein were not in fact superhuman, but simply plagiarists, copying great stuff from the future?

On Tuesday

, January 20, 2004, I sent Joel Bleifuss, my editor at

In These Times

, this fax:

ON ORANGE ALERT HERE. ECONOMIC TERRORIST ATTACK EXPECTED AT

8

PM EST. KV

Worried, he called, asking what was up. I said I would tell him when I had more complete information on the bombs George Bush was set to deliver in his State of the Union address.

That night I got a call from my friend, the out-of-print-science-fiction writer Kilgore Trout. He asked me, “Did you watch the State of the Union address?”

“Yes, and it certainly helped to remember what the great British socialist playwright George Bernard Shaw said about this planet.”

“Which was?”

“He said, ‘I don’t know if there are men on the moon, but if there are, they must be using the earth as their lunatic asylum.’ And he wasn’t talking about the germs or the elephants. He meant we the people.”

“Okay.”

“You don’t think this is the Lunatic Asylum of the Universe?”

“Kurt, I don’t think I expressed an opinion one way or the other.”

“We are killing this planet as a life-support system with the poisons from all the thermodynamic whoopee we’re making with atomic energy and fossil fuels, and everybody knows it, and practically nobody cares. This is how crazy we are. I think the planet’s immune system is trying to get rid of us with AIDS and new strains of flu and tuberculosis, and so on. I think the planet should get rid of us. We’re really awful animals. I mean, that dumb Barbra Streisand song, ‘People who need people are the luckiest people in the world’—she’s talking about cannibals. Lots to eat. Yes, the planet is trying to get rid of us, but I think it’s too late.”

And I said good-bye to my friend, hung up the phone, sat down and wrote this epitaph: “The good Earth—we could have saved it, but we were too damn cheap and lazy.”

I used to be the owner and manager of

an automobile dealership in West Barnstable, Massachusetts, called Saab Cape Cod. It and I went out of business thirty-three years ago. The Saab then, as now, was a Swedish car, and I now believe my failure as a dealer so long ago explains what would otherwise remain a deep mystery: Why the Swedes have never given me a Nobel Prize for Literature. Old Norwegian proverb: “Swedes have short dicks but long memories.”

Listen: The Saab back then had only one model, a bug like a VW, a two-door sedan, but with the engine in front. It had suicide doors opening into the slipstream. Unlike all other cars, but like your lawnmower and your outboard, it had a two-stroke rather than a four-stroke engine. So every time you filled your tank with gas, you had to pour in a can of oil as well. For whatever reason, straight women did not want to do this.

The chief selling point was that a Saab could drag a VW at a stoplight. But if you or your significant other had failed to add oil to the last tank of gas, you and the car would then become fireworks. It also had front-wheel drive, of some help on slippery pavements or when accelerating into curves. There was this as well: As one prospective customer said to me, “They make the best watches. Why wouldn’t they make the best cars, too?” I was bound to agree.

The Saab back then was a far cry from the sleek, powerful, four-stroke yuppie uniform it is today. It was the wet dream, if you like, of engineers in an airplane factory who’d never made a car before. Wet dream, did I say? Get a load of this: There was a ring on the dashboard, connected to a chain running over pulleys in the engine compartment. Pull on it, and at the far end it would raise a sort of window shade on a spring-loaded roller behind the front grill. That was to keep the engine warm while you went off somewhere. So, when you came back, if you hadn’t stayed away too long, the engine would start right up again.

But if you stayed away too long, window shade or not, the oil would separate from the gas and sink like molasses to the bottom of the tank. So when you started up again, you would lay down a smokescreen like a destroyer in a naval engagement. And I actually blacked out the whole town of Woods Hole at high noon that way, having left a Saab in a parking lot there for about a week. I am told old timers there still wonder out loud about where all that smoke could have come from. I came to speak ill of Swedish engineering, and so diddled myself out of a Nobel Prize.

It’s damn hard

to make jokes work. In

Cat’s Cradle

, for instance, there are these very short chapters. Each one of them represents one day’s work, and each one is a joke. If I were writing about a tragic situation, it wouldn’t be necessary to time it to make sure the thing works. You can’t really misfire with a tragic scene. It’s bound to be moving if all the right elements are present. But a joke is like building a mousetrap from scratch. You have to work pretty hard to make the thing snap when it is supposed to snap.

I still listen to comedy, and there’s not much of that sort around. The closest thing is the reruns of Groucho Marx’s quiz show,

You Bet Your Life

. I’ve known funny writers who stopped being funny, who became serious persons and could no longer make jokes. I’m thinking of Michael Frayn, the British author who wrote

The Tin Men

. He became a very serious person. Something happened in his head.

Humor is a way of holding off how awful life can be, to protect yourself. Finally, you get just too tired, and the news is too awful, and humor doesn’t work anymore. Somebody like Mark Twain thought life was quite awful but held the awfulness at bay with jokes and so forth, but finally he couldn’t do it anymore. His wife, his best friend, and two of his daughters had died. If you live long enough, a lot of people close to you are going to die.

It may be that I am no longer able to joke—that it is no longer a satisfactory defense mechanism. Some people are funny, and some are not. I used to be funny, and perhaps I’m not anymore. There may have been so many shocks and disappointments that the defense of humor no longer works. It may be that I have become rather grumpy because I’ve seen so many things that have offended me that I cannot deal with in terms of laughter.

This may have happened already. I really don’t know what I’m going to become from now on. I’m simply along for the ride to see what happens to this body and this brain of mine. I’m startled that I became a writer. I don’t think I can control my life or my writing. Every other writer I know feels he is steering himself, and I don’t have that feeling. I don’t have that sort of control. I’m simply becoming.

All I really wanted to do was give people the relief of laughing. Humor can be a relief, like an aspirin tablet. If a hundred years from now people are still laughing, I’d certainly be pleased.

I apologize to all

of you who are the same age as my grandchildren. And many of you reading this are probably the same age as my grandchildren. They, like you, are being royally shafted and lied to by our Baby Boomer corporations and government.

Yes, this planet is in a terrible mess. But it has always been a mess. There have never been any “Good Old Days,” there have just been days. And as I say to my grandchildren, “Don’t look at me. I just got here.”

There are old poops who will say that you do not become a grown-up until you have somehow survived, as they have, some famous calamity—the Great Depression, the Second World War, Vietnam, whatever. Storytellers are responsible for this destructive, not to say suicidal, myth. Again and again in stories, after some terrible mess, the character is able to say at last, “Today I am a woman. Today I am a man. The end.”

When I got home from the Second World War, my Uncle Dan clapped me on the back, and he said, “You’re a man now.” So I killed him. Not really, but I certainly felt like doing it.

Dan, that was my bad uncle, who said a male can’t be a man unless he’d gone to war.

But I had a good uncle, my late Uncle Alex. He was my father’s kid brother, a childless graduate of Harvard who was an honest life-insurance salesman in Indianapolis. He was well-read and wise. And his principal complaint about other human beings was that they so seldom noticed it when they were happy. So when we were drinking lemonade under an apple tree in the summer, say, and talking lazily about this and that, almost buzzing like honeybees, Uncle Alex would suddenly interrupt the agreeable blather to exclaim, “If this isn’t nice, I don’t know what is.”

So I do the same now, and so do my kids and grandkids. And I urge you to please notice when you are happy, and exclaim or murmur or think at some point, “If this isn’t nice, I don’t know what is.”

We are not born

with imagination. It has to be developed by teachers, by parents. There was a time when imagination was very important because it was the major source of entertainment. In 1892 if you were a seven-year-old, you’d read a story—just a very simple one—about a girl whose dog had died. Doesn’t that make you want to cry? Don’t you know how that little girl feels? And you’d read another story about a rich man slipping on a banana peel. Doesn’t that make you want to laugh? And this imagination circuit is being built in your head. If you go to an art gallery, here’s just a square with daubs of paint on it that haven’t moved in hundreds of years. No sound comes out of it.

The imagination circuit is taught to respond to the most minimal of cues. A book is an arrangement of twenty-six phonetic symbols, ten numerals, and about eight punctuation marks, and people can cast their eyes over these and envision the eruption of Mount Vesuvius or the Battle of Waterloo. But it’s no longer necessary for teachers and parents to build these circuits. Now there are professionally produced shows with great actors, very convincing sets, sound, music. Now there’s the information highway. We don’t need the circuits any more than we need to know how to ride horses. Those of us who had imagination circuits built can look in someone’s face and see stories there; to everyone else, a face will just be a face.

And there, I’ve just used a semi-colon, which at the outset I told you never to use. It is to make a point that I did it. The point is: Rules only take us so far, even good rules.

Who was the wisest

person I ever met in my entire life? It was a man, but of course it needn’t have been. It was the graphic artist Saul Steinberg, who like everybody else I know, is dead now. I could ask him anything, and six seconds would pass, and then he would give me a perfect answer, gruffly, almost a growl. He was born in Romania, in a house where, according to him, “the geese looked in the windows.”

I said, “Saul, how should I feel about Picasso?”

Six seconds passed, and then he said, “God put him on Earth to show us what it’s like to be

really

rich.”

I said, “Saul, I am a novelist, and many of my friends are novelists and good ones, but when we talk I keep feeling we are in two very different businesses. What makes me feel that way?”

Six seconds passed, and then he said, “It’s very simple. There are two sorts of artists, one not being in the least superior to the other. But one responds to the history of his or her art so far, and the other responds to life itself.”

I said, “Saul, are you

gifted

?”

Six seconds passed, and then he growled, “No, but what you respond to in any work of art is the artist’s struggle against his or her limitations.”