Read A Mountain of Crumbs: A Memoir Online

Authors: Elena Gorokhova

A Mountain of Crumbs: A Memoir (43 page)

“Pishi,”

she whispers, “promise to write often.” New tears swell in her eyes and spill over. “Are you sure you have everything?” she asks, swallowing and blinking. “Did you take the scarf I left out for you?” She swipes a finger under her eyes, folds her hot hands around mine, and I feel something small and heavy drop into my palm. “Take this with you. It’s your grandma’s watch, solid gold, French. They don’t make them anymore.”

I know that the law prohibits taking out of the country anything made before 1957, anything made in a foreign country, anything made of gold. But at this moment the law is as irrelevant as the visiting students with their machine-gun Spanish. I hold the watch in my palm, then drop it in the pocket of my jeans.

“We’ll come to visit you,” says Gris. “First we’ll send Mama, as soon as she’s done with the dacha and her apple jams. Then Marina will be next, and then we’ll all be there and you won’t know how to get rid of us.”

“Yeah,” I say and give Mama a smile. “I’ll start the paperwork as soon as I land.”

The current of the student group picks me up and carries me to the glass door, the border demarcation between us and the rest of the world. Behind it, in an automatic movement, a customs official in a gray uniform begins to riffle through my bag. I recognize him from my senior-year university lectures. He unwraps my bottles of perfume, one by one, lifts them up to the light, and stares at their contents. He opens my wallet and counts my money. He thumbs through the pages of my address book. A university graduate rummaging through luggage. He doesn’t recognize me, or pretends not to. Feeling the metal of the watch on my thigh, I look into his eyes, the deadened KGB eyes that can still, as long as I am in the international airport zone, drill right through my untrustworthy head, accuse me of being unpatriotic and delinquent, and order me to stay here. We stare at each other until he looks away—a philologist of Germanic languages busy analyzing underwear and socks—and pushes my violated suitcase off the belt.

When I finish repacking, I look back, at all of them clustered together before the glass door. Nina waves vigorously over my mother’s head. Gris stands next to her, his cap pushed over his forehead, his hands in his pockets. Marina is trying to shove in front of the guard, squeezing him out with her shoulder. I can only see a part of Mama, a small fragment of her face, her hand with a handkerchief blotting her eye.

If my father were alive, would he be standing next to her, waving me good-bye, reassuring me I won’t end up under a bridge? Or would he be fuming at a friend’s dacha, angry at my leaving, doing what he did when I was born? He was as stubborn as a goat, according to my mother, just like I am. I think of the dream I had about him when I was eight, in which he sat in his rowboat and spoke about theater, about the audience holding their breath and growing silent the moment before the curtain is about to go up. The anticipation of magic, he called it, the expectation of illusion. The moment when the noise stops. The moment you’re no longer ordinary.

I wonder whether in real life he knew anything about magic. Could he have recognized that moment, my unknown father?

Can I?

“Walk forward, let’s go,” commands a border patrolwoman, pushing me toward a metal detector that doesn’t work. But we have to pretend it does, and I obediently step through the metal arch, benevolently silent. When I am done, the border woman turns to the two British-looking ladies in pantsuits, explaining to them with her hands that they must pretend, too.

I stand on the other side of the world, looking back, saying goodbye. I think of the bulky clouds chugging over the city toward the Baltic Sea, pausing over my courtyard. I think of pocked walls, windowsills covered with soot, crumbling stairs leading to doors permanently barred. I think of the dilapidated sandbox in the middle of the playground. On its ledge crouches a small girl with braids. I know that face: green eyes slightly slanted, betraying the drop of Tatar ancestry in every Russian; faint freckles, as if someone had splashed muddy water onto her skin.

She looks up at me, and the bows in her skinny braids flutter like butterflies. I squat next to her, but the freckles grow darker, a wave of pink floods her cheeks, and her slanted eyes evade mine. She is tense and distant, like the still lindens behind her, like this mute courtyard, like prematurely aged Leningrad. A flock of pigeons pecking at the dirt lift their wings and with a startling clatter rustle up to where the wind rattles over the rooftops. We sit there in the sandbox, on different sides of the world, caught in a time warp—both waiting, both staring at the square of the courtyard sky and wondering what lies beyond it.

When I look back again, my family and friends are no longer visible. All I see through the horseshoe of the broken metal detector, all that is left of my country is a glare of glass.

Epilogue

M

Y MOTHER WALKS AROUND

my house switching off lights. She unloads my dishwasher, sweeps the leaves off the patio, and feeds the dog. She arrived here twenty-one years ago, when I waddled through my last weeks of pregnancy, her hair as white as our winter courtyard. According to my sister, it was my divorce from Robert—our different brains, the hot strangeness of Texas—that precipitated that dramatic change in hair color. My remarriage to someone she hadn’t met, my husband of now twenty-eight years, did not make things better. No one could believe that my mother’s hair was brown and then a month later, white, and then brown again once she settled with us in Nutley, New Jersey.

On the way home from Kennedy Airport, where she landed in June 1988, after we rolled across Manhattan toward the Lincoln Tunnel, a young woman in tight shorts approached our car at a red light on Forty-second Street. My husband turned his head toward her, and as she lifted her tank top above her chest, my mother winced and stiffened. I knew what she was thinking. She had been right all along, lying awake at night, combing through newspaper headlines for crumbs of transatlantic news. America is the mouth of a shark, just as

Pravda

had promised.

Much has happened since then. In 1991, we watched the Red Square barricades on CNN and gaped at Yeltsin perched on an armored vehicle with his arm thrust into the future in front of the Moscow Parliament called the White House. After that, the map of the Soviet Union shrank at the edges, Leningrad became St. Petersburg again, and

Pravda

ceased to exist. The English department of my university opened a private division where learning English is no longer free; the dean turned from guarding the party standards to investing in privatized oil companies. Marina answered a personal ad from a Louisiana newspaper and married a good man who loves her cooking and her sewing. She gave up acting and now devotes her talent to cultivating persimmons and tomatoes in a suburb of New Orleans. The rate for international phone calls dropped from three dollars a minute to two cents.

My mother still reuses paper napkins and plastic bags from the supermarket produce section, neatly folding and piling them under her bed. In her basement apartment, she reads memoirs about the Great Patriotic War and watches Russian National Television, which is again owned and controlled by the government, just as it was when I lived there. Between Moscow news and militia dramas, she fills a notebook with stories from her past. Every week, she dials her sister Muza and her stepdaughter Galya back in Russia and tells them all about our life here. She tells them about her ninety-fifth birthday party, when Marina flew here and cooked for two days; she mails them packages with gloves and sweaters, the necessary warm things.

She no longer needs to control and protect. There are no commissars and no lines bristling with elbows; there is no KGB, or shortage of mayonnaise. But old habits linger, and I have to catch myself not to react as I used to when out of the deep new pleats of skin gleam the eyes of my Leningrad mother. Every time I load her shopping cart with buckwheat and cottage cheese, she questions the prices and scrutinizes her receipts in search of errors, ready to find she’s been deceived by greedy cashiers. She gives us a slant-eyed look when we go to a restaurant, in brazen disregard of the refrigerator full of perfectly good food. But she is also practical, my mother. She knows her life is good, and as her saying goes, “When things are good you don’t search for better.” On holidays, she buys us cards with puppies and roses. To help me, she cuts out quick dinner recipes and piles them on the kitchen counter, along with advice on college majors for my daughter from the Russian-language newspaper published in Brooklyn.

I am the one now who worries about scarves and schools, soup and order. I am the one expected to protect and control. In my head, pictures of the perfect life grow like our dacha strawberries, in model rows. I want my daughter to speak Russian, to read Turgenev, to memorize Pushkin’s verse the same way we memorized it in school. I want her to love theater and spend nights in the kitchen pontificating about personal happiness and the meaning of life. I want to infect her with the germ of Russia so she stops being American and becomes like me.

But I don’t. My daughter’s native language is English, and KGB and

Pravda

are just the names of expensive bars in New York.

In my New Jersey house, with my mother’s apartment the size of our place in Leningrad, we all enjoy privacy, something I tried to find in the Russian language and my Russian life, something that didn’t exist there. I’m glad I left that life twenty-nine years ago; I’m happy my family is here with me. I am closer to my mother and sister now than I ever was in Leningrad. But then, we are probably not the same people we were back in Russia. In our private American space, we can splice the cleaved halves of our souls and heal; we can change if we want to—transform ourselves, as my actress sister knows how to do—and no one will say we’ve betrayed the collective. We can simply live, and keep the door open, and wait. We can be in flux, just like the new Russia.

“Whatever happens, happens for the best, as Mamochka used to say,” murmurs my creased, once again white-haired mother. Her

mamochka,

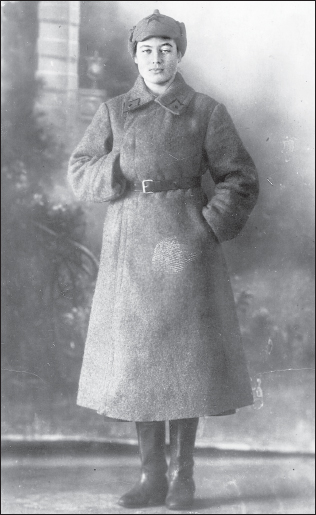

my grandma, as soft and wrinkled, smiles at us from a photograph on the wall, which hangs next to my young mother’s portrait, painted by her brother Sima. We don’t talk about such things as forgiveness, understanding, acceptance. We simply sip black currant tea, my mother’s favorite, and I don’t say anything to question Grandma’s wisdom.

Acknowledgments

I

AM DEEPLY GRATEFUL TO

my agent, Molly Friedrich, extraordinary in every way, for taking a chance on this first memoir and for guiding me ever since; to my editor, Priscilla Painton, for her insight, grace, and sharp eye; and to Jacobia Dahm, my reader who first called it “a book.” My gratitude also goes to Victoria Meyer, executive director of publicity at Simon & Schuster, for her enthusiasm about the book, and to Loretta Denner, for her exactitude and style. Lucy Carson, Michael Szczerban, and Dan Cabrera, thank you for your support.

The inspiration for this memoir came from Frank McCourt’s seminar at the Southampton Writers Conference, where the intelligence and energy of my exceptional classmates challenged expectations and created magic. I have learned from the conference’s many mentors and friends, and I am grateful for their wisdom and gracious advice. My special thanks to Robert Reeves, the conference director, and Jody Donohue, a poet and a friend.

I am thankful to my fellow writers Pearl Solomon, Patricia Hackbarth, and Ruth Hamel, whose suggestions have improved many chapters; to Nadia Carey, an old friend from Leningrad, for setting some facts straight; and to Eleanor Oakley for her enormous heart.

My appreciation goes to Donna Perreault of

The Southern Review,

Stephanie G’Schwind of

Colorado Review,

Robert Stewart of

New Letters,

and Lou Ann Walker of the

Southampton Review

for publishing chapters from the memoir; and to Juris Jurjevics of Soho Press for his generous support. My gratitude to the late Staige D. Blackford of

The Virginia Quarterly Review

for his kind words dating back to the twentieth century, the first encouragement I received from an editor.

Spasibo

to Irina Veletskaya, Anna Graham, Luba Borisova, and Olga Kapitskaya for their friendship, the Russian kind.

I thank my sister Marina for her soul filled with talent and my mother for her head filled with memories. Also, I am indebted to my remaining family in Russia, although they would have probably told a different story of our past.

And finally, this book would not be possible without the two closest people: Laurenka, who may have been touched by Russia more than she knows, and Andy, my most ardent advocate, exacting reader, and unwavering supporter since my first years in this country, when the English language was still a mystery. To you, my love.

Other books

The Things They Cannot Say by Kevin Sites

The Dark and Deadly Pool by Joan Lowery Nixon

Veil of Silence by K'Anne Meinel

Complete We (A Her Billionaires Novella #4) by Kent, Julia

Maddy's Dolphin by Imogen Tovey

Starving for Love by Nicole Zoltack

Never Love a Scoundrel by Darcy Burke

A Time To Kill (Elemental Rage Book 1) by Jeanette Raleigh

Tiempo de arena by Inma Chacón