A People's Tragedy (21 page)

Read A People's Tragedy Online

Authors: Orlando Figes

It was the key to their social betterment. This cultural divide was to be a major feature of the peasant revolution. One part of it was progressive and reforming: it sought to bring the village closer to the influences of the modern urban world. But another part of the peasant revolution was restorationist: it tried to defend the traditional village against these very influences. We shall see how these two conflicting forces affected the life of a single village when we turn to the story of Sergei Semenov and the revolution in Andreevskoe.

Nevertheless, despite these modernizing forces, the basic structure of peasant politics remained essentially patriarchal. Indeed the upholders of the patriarchal order had a whole range of social controls with which to stem the tide of modernity. In every aspect of the peasants' lives, from their material culture to their legal customs, there was a relentless conformity. The peasants all wore the same basic clothes. Even their hairstyles were the same — the men with their hair parted down the middle and cut underneath a bowl, the women's hair plaited, until they were married, and then covered with a scarf. The peasants in the traditional village were not supposed to assert their individual identity, as the people of the city did, by a particular fashion of dress. They had very little sense of privacy. All household members ate their meals from a common pot and slept together in one room. Lack of private spaces, not to speak of fertility rites, dictated that the sexual act was kept at least partly in the public domain. It was still a common practice in some parts of Russia for a peasant bride to be deflowered before the whole village; and if the groom proved impotent, his place could be taken by an older man, or by the finger of the matchmaker. Modesty had very little place in the peasant world. Toilets were in the open air. Peasant women were constantly baring their breasts, either to inspect and fondle them or to nurse their babies, while peasant men were quite unselfconscious about playing with their genitals. Urban doctors were shocked by the peasant customs of spitting into a persons eye to get rid of sties, of feeding children mouth to mouth, and of calming baby boys by sucking on their penis.14

The huts of the peasants, both in their external aspect and in their internal layout and furnishings, conformed to the same rigid pattern that governed the rest of their lives.

Throughout Russia, in fact, there were only three basic types of peasant housing: the northern

izba,

or log hut, with the living quarters and outbuildings all contained under one roof around a quadrangle; the southern

izba,

with the outbuildings separate from the living quarters; and the Ukrainian

khata,

again a separate building made of wood or clay, but with a thatched roof. Every hut contained the same basic elements: a cooking space, where the stove was located, upon which the peasants (despite the cockroaches) liked to sleep; a 'red'* or 'holy' corner, where the icons were hung, guests were entertained, and the family ate around a whitewashed table; and a sleeping area, where in winter it was common to find goats, foals and calves bedded down in the straw alongside the humans. The moist warmth and smell of the animals, the black fumes of the kerosene lamps, and the pungent odour of the home-cured tobacco, which the peasants smoked rolled up in newspaper, combined to create a unique, noxious atmosphere. 'The doors are kept vigorously closed, windows are hermetically sealed and the atmosphere cannot be described,' wrote an English Quaker from one Volga village.

'Its poisonous quality can only be realised by experience.' Given such unsanitary conditions, it is hardly surprising that even as late as the 1900s one in four peasant babies died before the age of one. Those who survived could expect to live in poor health for an average of about thirty-five years.15 Peasant life in Russia really was nasty, brutish and short.

It was also cramped by strict conformity to the social mores of the village. Dissident behaviour brought upon its perpetrators various punishments, such as village fines, ostracism, or some sort of public humiliation. The most common form of humiliation was 'rough music', or

charivari,

as it was known in

* The Russian word for red

(krasnyi)

is connected with the word for beautiful

(krasivyt),

a fact of powerful symbolic significance for the revolutionary movement.

southern Europe, where the villagers made a rumpus outside the house of the guilty person until he or she appeared and surrendered to the crowd, who would then subject him or her to public shame or even violent punishment. Adulterous wives and horse-thieves suffered the most brutal punishments. It was not uncommon for cheating wives to be stripped naked and beaten by their husbands, or tied to the end of a wagon and dragged naked through the village. Horse-thieves could be castrated, beaten, branded with hot irons, or hacked to death with sickles. Other transgressors were known to have had their eyes pulled out, nails hammered into their body, legs and arms cut off, or stakes driven down their throat. A favourite punishment was to raise the victim on a pulley with his feet and hands tied together and to drop him so that the vertebrae in his back were broken; this was repeated several times until he was reduced to a spineless sack. In another form of torture the naked victim was wrapped in a wet sack, a pillow was tied around his torso, and his stomach beaten with hammers, logs and stones, so that his internal organs were crushed without leaving any external marks on his body.16

It is difficult to say where this barbarism came from — whether it was the culture of the Russian peasants, or the harsh environment in which they lived. During the revolution and civil war the peasantry developed even more gruesome forms of killing and torture.

They mutilated the bodies of their victims, cut off their heads and disgorged their internal organs. Revolution and civil war are extreme situations, and there is no guarantee that anyone else, regardless of their nationality, would not act in a similar fashion given the same circumstances. But it is surely right to ask, as Gorky did in his famous essay 'On the Russian Peasantry' (1922), whether in fact the revolution had not merely brought out, as he put it, 'the exceptional cruelty of the Russian people'? This was a cruelty made by history. Long after serfdom had been abolished the land captains exercised their right to flog the peasants for petty crimes. Liberals rightly warned about the psychological effects of this brutality. One physician, addressing the Kazan Medical Society in 1895, said that it 'not only debases but even hardens and brutalizes human nature'. Chekhov, who was also a practising physician, denounced corporal punishment, adding that 'it coarsens and brutalizes not only the offenders but also those who execute the punishments and those who are present at it'.17 The violence and cruelty which the old regime inflicted on the peasant was transformed into a peasant violence which not only disfigured daily village life, but which also rebounded against the regime in the terrible violence of the revolution.

If the Russian village was a violent place, the peasant household was even worse. For centuries the peasants had claimed the right to beat their wives. Russian peasant proverbs were full of advice on the wisdom of such beatings:

'Hit your wife with the butt of the axe, get down and see if she's breathing. If she is, she's shamming and wants some more.'

'The more you beat the old woman, the tastier the soup will be.'

'Beat your wife like a fur coat, then there'll be less noise.'

A wife is nice twice: when she's brought into the house [as a bride] and when she's carried out of it to her grave.'

Popular proverbs also put a high value on the beating of men: 'For a man that has been beaten you have to offer two unbeaten ones, and even then you may not clinch the bargain.' There were even peasant sayings to suggest that a good life was not complete without violence: 'Oh, it's a jolly life, only there's no one to beat.' Fighting was a favourite pastime of the peasants. At Christmas, Epiphany and Shrovetide there were huge and often fatal fist-fights between different sections of the village, sometimes even between villages, the women and children included, accompanied by heavy bouts of drinking. Petty village disputes frequently ended in fights. 'Just because of a broken earthenware pot, worth about 12 kopecks,' Gorky wrote from his time at Krasnovidovo,

'three families fought with sticks, an old woman's arm got broken and a young boy had his skull cracked. Quarrels like this happened every week.'18 This was a culture in which life was cheap and, however one explains the origins of this violence, it was to play a major part in the revolution.

Many people explained the violence of the peasant world by the weakness of the legal order and the general lawlessness of the state. The Emancipation had liberated the serfs from the judicial tyranny of their landlords but it had not incorporated them in the world ruled by law, which included the rest of society. Excluded from the written law administered through the civil courts, the newly liberated peasants were kept in a sort of legal apartheid after 1861. The tsarist regime looked upon them as a cross between savages and children, and subjected them to magistrates appointed from the gentry.

Their legal rights were confined to the peasant-class courts, which operated on the basis of local custom. The peasants were deprived of many civil rights taken for granted by the members of other social estates. Until 1906, they did not have the right to own their allotments. Legal restrictions severely limited their mobility. Peasants could not leave the village commune without paying off their share of the collective tax burden or of the redemption payments on the land gained from the nobles during the Emancipation. For a household to separate from the commune, a complex bureaucratic procedure was necessary, requiring the consent of at least two-thirds of the village assembly, and this was difficult to

obtain.* Even a peasant wanting to leave the village for a few weeks on migrant labour could not do so without first obtaining an internal passport from the commune's elders (who were usually opposed to such migration on the grounds that it weakened the patriarchal household and increased the tax burden on the rest of the village). Statistics show that the issuing of passports was heavily restricted, despite the demands of industrialization and commercial agriculture for such migrant labour.19 The peasants remained tied to the land and, although serfdom had been abolished, it enjoyed a vigorous afterlife in the regulation of the peasant. Deprived of the consciousness and the legal rights of citizenship, it is hardly surprising that the peasants respected neither the state's law nor its authority when its coercive power over them was removed in 1905

and again in 1917.

* * * It is mistaken to suppose, as so many historians do, that the Russian peasantry had no moral order or ideology at all to substitute for the tsarist state. Richard Pipes, for example, in his recent history of the revolution, portrays the peasants as primitive and ignorant people who could only play a destructive role in the revolution and who were therefore ripe for manipulation by the Bolsheviks. Yet, as we shall see, during 1917—

18 the peasants proved themselves quite capable of restructuring the whole of rural society, from the system of land relations and local trade to education and justice, and in so doing they often revealed a remarkable political sophistication, which did not well up from a moral vacuum. The ideals of the peasant revolution had their roots in a long tradition of peasant dreaming and Utopian philosophy. Through peasant proverbs, myths, tales, songs and customary law, a distinctive ideology emerges which expressed itself in the peasants' actions throughout the revolutionary years from 1902 to 1921.

That ideology had been shaped by centuries of opposition to the tsarist state. As Herzen put it, for hundreds of years the peasant's 'whole life has been one long, dumb, passive opposition to the existing order of things: he has endured oppression, he has groaned under it; but he has never accepted anything that goes on outside the life of the commune'.20 It was in this cultural confrontation, in the way that the peasant looked at the world outside his village, that the revolution had its roots.

Let us look more closely at this peasant world-view as expressed in customary law.

Contrary to the view of some historians, peasant customary law

* Even in communes with hereditary tenure (mainly in the north-west and the Ukraine) it was hardly easier. There the household wishing to separate had either to pay off its share of the communal tax debt in full (a near-impossible task for the vast majority of the peasants) or find another household willing to take over the tax burden in return for its land allotment. Since the taxes usually exceeded the cost of rented land outside the commune, it was difficult to find a household willing to do this.

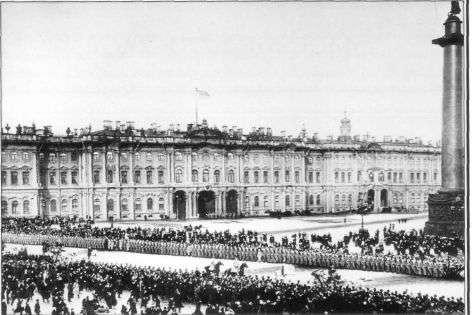

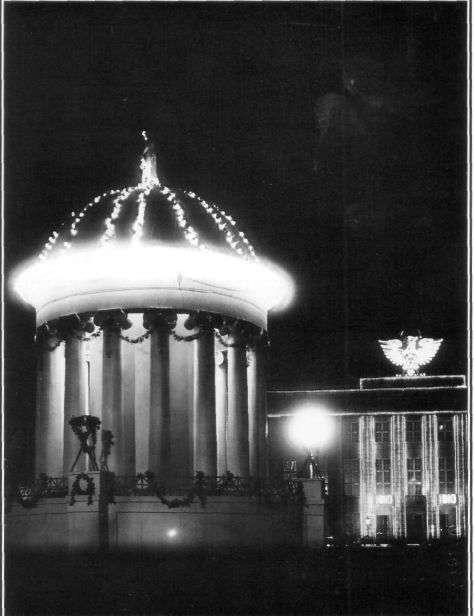

IMAGES OF AUTOCRACY

1 St Petersburg illuminated for the Romanov tercentenary in 1913. This electric display of state power was the biggest light show in tsarist history.