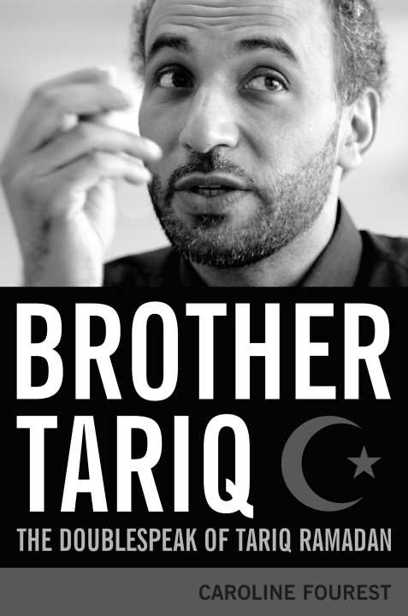

Brother Tariq: The Doublespeak of Tariq Ramadan

Read Brother Tariq: The Doublespeak of Tariq Ramadan Online

Authors: Caroline Fourest

THE DOUBLESPEAK OF TARIQ RAMADAN

The Doublespeak of Tariq Ramadan

CAROLINE FOUREST

Translated into English by

Ioana Wieder and John Atherton

Preface

xiii

Part 1 TARIQ RAMADAN: His RECORD AND BACKGROUND

I

I "Islarris Future" or the Future of 3 the Muslim Brotherhood?

Part 2 DISCOURSE AND RHETORIC 109

3 A "Reformist" but a Fundamentalist

III

4 An "Islamic Feminist"137 but Puritanical and Patriarchal

5 Muslim and Citizen, but Muslim First!

166

6 Not a Clash but a Confrontation 196 between Civilizations

7 The West as the Land of "Collaborations"

226

Notes

235

Index

255

Triq Ramadan is a global phenomenon, speaking and writing as he

does with such great fluency in French, Arabic, and English. Not for centuries has Switzerland had a native son who enjoyed such fame and impact as

a communicator. In Europe, he is the most quoted and circulated writer on

his religion, Islam, and on the issues related to the Muslim community in

Europe and further afield.

Despite being an author with several books to his name, and a regular

contributor to the opinion pages of the world's newspapers, it is at rallies in

France, or at Muslim gatherings in Africa, the Middle East, and elsewhere

that Tariq Ramadan makes many of the telling interventions that reveal his

thinking and his ambitions. Most are recorded, to be played later to a wider

audience, as guidance or as religious-political talks. Caroline Fourest has

done us a great service by listening to, transcribing, and translating Ramadan's words, since the picture on offer to those who only read his books or

columns in English, or who only hear him speak at conferences in Britain, is

necessarily limited. Ramadan grew up in a Francophone culture and spoke

Arabic from birth. His profile is very different in France and in Switzerland,

and for anyone who seeks to understand him, this biography is essential

reading.

In spite of having been born in Switzerland and educated in the Frenchspeaking part of that country (the question of his higher academic qualifications and the reasons that led him to quit his job as a schoolteacher make

interesting reading), Ramadan stresses his family background as the grandson of the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood and as the son of the main

propagator and propagandist of Muslim Brotherhood ideas beyond Egypt

after 1950.

For most of the twentieth century, the different currents of religious politics in the Muslim world were little known beyond a narrow circle of specialists in Europe's universities and research institutes. The politics of the Arab

world, particularly in the second half of the last century, saw a confusing mixture of regimes-some cast in a nationalist, socialist, fascistic, or authoritarian European mold, others based on absolute monarchies blessed with

unlimited oil wealth.

The interstices of ideology and religious belief are difficult to trace. The

abolition of the Caliphate and the rise of a proto-modern state, Turkey, with

its largely Muslim population, further complicate the picture-as indeed do

the quarrels between different branches of Islam, notably the Sunni-Shia

conflict.

A further twist of the kaleidoscope of political and religious identity in

the Arab world came from the issue of the Jewish right to create a state called

Israel in a part of the world that Jews had inhabited continuously for much

longer than Christians or Muslims had lived in lands that they claimed as

their own. Add to this the various struggles for national identity, as French

and British colonialisms were dismantled ...

The great movements of people and ideas over the past half century have

resulted in the development of major Muslim communities in Europe: in

Britain, with links to Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh; in France, with links

to the Mahgreb; and in Germany, with links to Turkey. The Islam of these

new communities has varied, but, as there turned out to be no easy solution

to the problems of social equality, acceptance in political and civil society, or

economic opportunity, the issue of religion/ideology and identity became

more pressing.

The development of Muslim communities in Europe coincided with

the last quarter of the twentieth century, when it seemed that the best values of Europe-those associated with the Renaissance and the rationality

of Galileo, with the Enlightenment appeal of Voltaire to drive out superstition, with the welcome liberation of women and gays, and with freedom of

expression-were starting to gain the upper hand over conservative religiosity and the dominance of women by men. Under the umbrella of the Euro pean Union, nations turned their backs on conflict, decided that disputes

should be resolved by secular and democratic rule of law, and that the right of

people to speak, travel, and live their sexuality free from religious constraints

should be upheld.

I first came across Tariq Ramadan when I was working in Geneva before

my election to the House ofCommons in 19 94. It was the early r 9 dos, and he

was involved in an attempt by Muslim activists in Geneva to stop the production of a play by Voltaire. It is certainly true that Voltaire managed to insult

all religions, and he was odious about Christians, Jews, and Muslims alike.

But he is also commonly held to have coined the immortal phrase about disagreeing with what a person has to say but defending that persons right to

say it-a concept that makes the difference between life worth living and life

lived under the orders of authority from on high.

John Stuart Mill described "the necessity to the mental well-being ofman-

kind (on which all their other well-being depends) offreedom of opinion, and

freedom of the expression of opinion." I was deeply disturbed when the city

of Geneva (near which Voltaire lived, so that he could, if necessary, escape the

heavy hand of the religious and absolutist ancien regime of eighteenth-century France) refused to support freedom of expression, and instead allowed

religious ideology to impose censorship. Ramadan argued that it was a question of decency, or good manners, not to insult Muslim identity by staging

the Voltaire play. Mill also deals with this objection in his famous essay on

freedom of thought and discussion, pointing out the "impossibility of fixing"

where the "bounds of fair discussion" should be placed. To place religious

belief beyond the bounds of polemic and intellectual assault is to deny all of

Europe's heritage and values.