A Place of My Own (36 page)

Authors: Michael Pollan

On one of my visits to Jim’s, flipping through his racks of furniture stock, I pulled one pale board that wasn’t instantly identifiable but which, after I’d raised its grain with a drop of saliva, seemed oddly familiar. I asked him what I was looking at. White ash—of course. I knew it from a hundred garden-tool handles and, back much farther than that, from all those long moments spent in on-deck circles studying the sweeping grain and burnt-in logo on the loin of a Louisville Slugger. I picked up a short length of the ash and realized I had a specific sense memory of its weight, which always takes me slightly by surprise; the wood’s paleness prepares your hand for something light, on the order of pine, but ash has a real heft to it, and I knew it to the ounce.

Jim said ash was a fine choice for a desk, even though you didn’t see it used that way too often. The wood was hard and wore nicely, yellowing slightly over time, its cream color turning to butter. I asked if I could take a piece of it home.

When I mentioned the idea of ash to Charlie, he was dubious at first, worried it might have the same contemporary associations that maple has, since it was nearly that white. But when I sanded my sample and rubbed a little tung oil into it, the hue of the wood grew warmer. It became apparent that its grain was far more vivid than maple’s, with loose, shadowy springwood rings standing out from the intervening regions of dense white summerwood. The pattern and the hue both reminded me of rippled beach sand.

I liked the look of the ash, and also the fact that the wood had no obvious stylistic associations. It made you think of tools before interiors, which I counted a plus, since this was after all a working surface I was making—a tool of a kind. I looked up “ash” in a couple of reference books, and what I read about the tree, which happens to be well represented on my land, gave me a fresh respect for it.

The variety of uses to which white ash has been put is truly impressive, the result of the wood’s unusual combination of strength and suppleness: Though hard, it is also pliant enough to take the shapes we give it and to absorb powerful blows without breaking. In addition to baseball bats and a great assortment of tools (including the handles of trowels, hammers, axes, and mallets and the shanks of scythes), I read that ash trees have been recruited over the years for church pews and bowling alleys, the D-handles of spades and shovels and the felloes, or rims, of wooden wheels (the wood obligingly holds its curve when steamed and bent), the oars and keels of small boats, garden and porch furniture, the slats of ladder-back chairs and the seats of swings, pump handles and butter-tub staves, archaic weapons of war including spears, pikes, battle-axes, lances, arrows, and cross-bows (some treaties gave Indians the right to cut ash on any land in America, no matter who owns it), snowshoes, ladder rungs, the axles of horse-drawn vehicles (the first automobiles and airplanes had ash frames), and virtually every piece of sports equipment that is made out of wood, including hockey sticks, javelins, tennis rackets, polo mallets, skis, parallel bars, and the runners on sleds and toboggans.

From the admiring accounts I read, one might conclude that white ash is up there with the opposable thumb in driving the advance of human civilization. It’s hard to think of a wood more obliging to man than ash—a tree that supplies the handles for the very axes used to cut down other trees. The reason ash makes such a satisfactory tool handle is that, in addition to its straight grain and supple strength, the wood is so congenial to our hands, wearing smooth with long use and hardly ever splintering. Ash is as useful, necessary, and dependable as work itself, and perhaps for that reason it is no more glamorous. As a tree, I confess I’d always taken the ash pretty much for granted, probably because it grows like a weed around here. But now I was sold. I would make my desk out of the most common tree on the property, the very tree that the window over my desk looked out on.

Ash boards proved somewhat harder to find than ash trees; it seems that most of the board feet cut each year go to makers of tools and sports equipment. Eventually I tracked down a local lumber mill, Berkshire Wood Products, that had a small quantity of native white ash in stock, mixed lengths of five quarter. (Charlie and Joe had both told me I’d be better off with native stock; having already been acclimated to the local air, it would be less likely to check or warp or otherwise surprise.)

Berkshire Wood Products consists of a small collection of ramshackle barns and sheds at the end of a long dirt road in the woods just over the state line in Massachusetts. The place had a distinct old-hippie air about it, with a big vegetable garden out front that was mulched with composted sawdust. Though only a tiny operation, the mill performed every step of the lumber-making process itself, cutting down the tree, milling the logs, kiln-drying the lumber, and dressing the planks to order.

The yardman invited me to select the boards I wanted, pointing to the very top of a three-story-tall rack that filled a large barn. To get to the ash I had to climb a scaffold, moving past handsome rough-sawn slabs of walnut, cherry, white pine, tulip wood, red oak, and yellow birch—most of the important furniture woods of the Northeastern forest. Many of the boards still had their bark, making them look more like tree slices than lumber. I reached the stack of ash and it was gorgeous stuff: eight-foot lengths of creamy white lumber, a handful of the boards set off with elliptical galaxies of nut-brown heartwood stretching out along the grain. Evidently brown heartwood is considered undesirable in ash, because when I expressed particular interest in these boards, the foreman offered to give me a discount.

Only after toting up the total board-foot price did the yardman begin dressing the lumber, much as if I were buying whole fishes I wanted filleted. Working together, he and I ran the best face of each board through the planer several times to remove the rotary scars left by the sawmill, and then used a laser-guided table saw to trim the boards lengthwise, removing the bark and wane and creating the perfectly straight and parallel edges I would need to join the boards cleanly. I realized from his banter that the yardman took me for a carpenter rather than a hobbyist; had I become so conversant in wood that I could actually pass? I loaded the ash in the back of my station wagon and headed home.

Our plan was to glue six of the boards together to make a big, roughly dimensioned plank from which we could then cut out the precise shape of the desk. As we lined up the boards on the floor I decided which ones I liked best and considered where in the finished desktop these should fall. Joe encouraged me to take my time about it: “You’re going to have to live with these boards a long time.” He clomped away while I ordered and reordered the boards, searching for the most pleasing pattern of grain and figuration. In my parents’ living room when I was growing up, there was an English walnut coffee table made by a Japanese woodworker named Nakashima, and the Rorschach-like burls and figures of that surface, which reminded me at various times of clouds and animals and monstrous faces, are printed on my memory as few images from that time are; I can still picture them, vivid and intimate as birthmarks. So I took my sweet time about it, making sure that the most interesting figures fell where, daydreaming at my desk, I would be able to dwell on them.

Once I was satisfied with the arrangement of boards, we painted their edges with wood glue, pressed them up against one another, and then secured the assembly with a pair of clamps, tightening until buttery beads of glue weeped from the seams. In a couple of hours, these six ash boards would be for all purposes one. We gave the assembly overnight to cure and then rough-sanded the surface with Joe’s belt sander, smoothing out the joints and removing the dried pearls of glue that had collected along the seams.

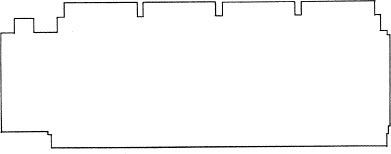

Now came the hard and truly harrowing part: cutting the slab to fit the building. Not only did the main section of the desk have to wrap around a corner post and fin wall at either end, but its back edge had to be cut into a toothy pattern matching the two-by-four studs beneath the window. This is how it had to look:

And this is the

platonic

version of the desktop’s configuration. I probably don’t have to mention that none of what appear in this drawing to be right angles could be exactly that in reality: the cutaway at upper right had to fit the notoriously twisted corner post—the probable cause of our unending headache—and the wing on either side had to be subtly trapezoidal, the right one a couple degrees less subtle than the left. The shape of this desk, in other words, represented the ultimate wages of our original geometrical sin. Less obvious but at least as perilous to our success was the fact that we had to work from the precise mirror image of this design penciled onto the underside of the desktop, since it is an axiom of woodworking that one always cuts from the back side of a finished wood surface in order to prevent the teeth of the saw from marring it.

Any significant error would mean driving back to Berkshire Products and starting all over again.

The day we cut the main section of the desk I remember as the day without small talk; not since my SATs had I put in so many consecutive hours of relentless, single-minded concentration. The subject of this particular test may only have been Euclidean geometry, but there were some hard problems on it calling for the rotation of an imaginary—and radically asymmetrical—object in space, and you weren’t allowed to use an eraser, either. So we measured every cut three, sometimes four times, interrogating each other’s every move, checking and rechecking lengths and angles and then reversals of angles before even contemplating picking up a saw. We worked in slow motion and virtual silence, every word between us a number. Joe actually gave gun control a rest, that was one good thing. The other was that the saw blade drew from the ash a faint breath of burnt sugar and popcorn.

We had taken care to leave each cut at least a blade’s-width too long, this being the only conceivable side to err on, so it took several tries before we managed to pound the desktop down into its tight and tricky pocket, but at last, and with a terrific screeching complaint of wood against wood, it went in. A drive fit. Not quite perfect—there were eighth-inch gaps here and there—but a damned sight closer than I’d ever thought we’d come. A rush of relief is what we mainly felt, our high-fives more exhausted than exultant, but they were no less sweet for that. Though I ran the risk of offending Joe by seeming so surprised, the job we’d done on this desk looked downright professional: here was an actual piece of furniture, and

we’d

made it. “Careful,” he cautioned, “a guy could get hurt patting himself on the back like that.”

I felt like we’d crossed over a crest of some kind, and from way up here the road ahead sloped down nicely, looking like it might even be smooth.

THE METAPHYSICS OF TRIM

THE METAPHYSICS OF TRIM

And for a while it was. The following weeks saw steady progress, no disasters. We laid and finished the floor, framed the steps and the daybed, and closed in the rear wall around the daybed with four-inch strips of clear pine. One unseasonably warm March Saturday we moved the operation outdoors, building and hanging the wooden visor over the front window. Charlie had said the cap visor would substantially alter the character of the building, and that it did, relaxing the formality of its classical face, giving it a definite outlook and a personality that seemed much more approachable. “You know, Mike, this building’s starting to look like you,” Joe announced after the visor went up; he was leaning back in an exaggerated way to fit me and the building into a frame formed with his hands, as if searching for the family resemblance. “Must be the baseball cap,” I said.

Joe and I worked methodically and well, achieving an easy collaboration on many of those early spring days. I began to feel less like a helper than a partner, and we traded off tasks depending on our mood rather than on the likelihood of my screwing up something important. I noticed that my finish nails seldom bent anymore (a good thing, too, when you’re nailing lengths of clear pine that cost $2 a linear foot), and the circular saw had lost its ability to startle me with short cuts or seize-ups. My grasp of wood behavior was daily growing surer, and I’d internalized all of Joe’s sawing saws, which now played in my head like a cautionary mantra: Measure twice cut once, consider all the consequences, remember to count the kerf (the extra eighth of an inch removed by the saw blade itself). As I grew more confident about making field decisions, phone calls to Charlie became infrequent, until one day, concerned about the long spell of radio silence from the job site, Charlie called

me

to see if there was anything we needed. Not that I could think of; we were rolling along. Some days I even got to be the head carpenter in charge, Joe manning the chop saw while I called for lengths of lumber. What it felt like now was a pretty good job, one poised on that fine-point where it is no longer daunting yet still reliably supplies days of novelty and challenge. The hours slipped by, and the end of each workday brought the satisfaction of markable progress and the solidifying conviction that this building was going to get done.