A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide (24 page)

Read A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide Online

Authors: Samantha Power

Tags: #International Security, #International Relations, #Social Science, #Holocaust, #Violence in Society, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #General, #United States, #Genocide, #Political Science, #History

Elizabeth Becker, the Washington Post metro reporter, had been clamoring to get back into Cambodia since she left in 1974. She had written more than a dozen letters paying what she remembers as "disgusting" homage to the KR's "glorious revolution" in the hopes of winning a visa. Whenever Ieng Sary visited the United Nations for the annual General Assembly session, Becker trekked up to New York to appeal to him in person. In November 1978 she received a telegram from the KR (postmarked from Beijing) inviting her to Cambodia. She was one of three Western guests chosen.

Becker did not hesitate for a second. All of the fears that had driven her from the country in 1974 had been overtaken by a desperate desire to peer behind the Khmer curtain. She felt as if she had been "put in a coffin" since the KR sealed the country. She remembers:

I hadn't guessed they would isolate themselves like they did. I mean, the idea that you could go to an airport and it would never say "Phnom Penh" on the departures board-that broke my heart. I had to go back to see what was happening. Since the KR were busy killing their own people, I didn't think they would make time for us. Nobody said, "Don't go"

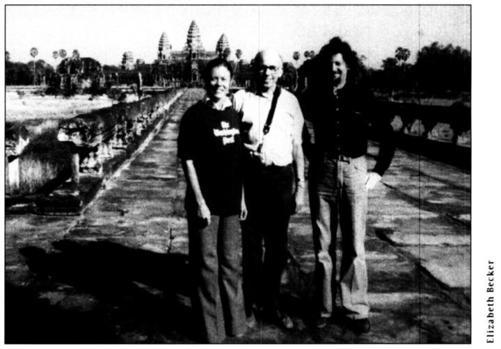

Becker and Richard Dudman of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch became the first American journalists to enter the country since the Khmer Rouge had seized Phnom Penh in April 1975. Joined by Australian academic Malcolm Caldwell, a leftist sympathizer with the KR regime, they arrived on a biweekly flight from China, the only country that retained landing rights in Cambodia. For the next ten days, Becker, Dudman, and Caldwell were given an "incubated tour of the revolution" that included immaculate parks, harangues about Vietnamese aggression, and screenings of propaganda films."' Throughout their stay, the three foreigners were forbidden from independently exploring.They spoke only with those who had been handpicked by Angkar to represent the KR, and even these meetings were steered by a guide who was present at all times. Nothing Becker's group saw resembled either what she remembered or what the refugees at the Thai border had described. Fishermen, rubber plantation workers, weavers, all were wheeled out to speak of the joys of the revolution and the bounty of their productivity.

Only when Becker sneaked out of her compound did she get a sense of what lay behind the Potemkin village. If Phnom Penh's main Monivong Boulevard was clean-shaven for the consumption of visitors, the surrounding streets were littered with stubble. Shops and homes had been weeded over. Furniture and appliances were stacked haphazardly. Just as many religious shrines in Bosnia would later be reduced to rubble overnight, so, too, the French cathedral and the picturesque pagodas had vanished without a trace. Even when she participated in the KR's regimented activities, Becker observed a country that was missing everything that signaled life. She later recalled, "There were no food-stalls, no funilies, no young people playing sports, even sidewalk games, no one out on a walk, not even dogs or cats playing in alleyways.""` When she spotted people out in the countryside, they were working joylessly, furiously, without contemplating rest. The country's stunning Buddhist temples had been converted into granaries.

From left: Elizabeth Becker, Richard Dudman, and Malcolm Caldwell at the Angkor Wat temples in December 1978.

It is difficult to imagine how confused Becker and the others must have been at that time. They had heard refugee reports of massacres and starvation. They suspected the number killed was in the hundreds of thousands. But they knew virtually nothing specific about the bloody Pol Pot regime. Becker was unable to muster the practical or moral imagination needed to envision the depths of what was happening behind the pristine and cheery front presented. She recalled:

We were the original three blind men trying to figure out the elephant. At that time no one understood the inner workings of the regime-how the zones operated; how the party controlled the country; how the secret police worked; that torture and extermination centers ... even existed; the depth of the misery and death.... We had the tail, the ears, the feet of the monster but no idea of its overall shape....';

By the time the two-week trip began winding down, the luster of being the first to visit had long since worn off. On December 22, 1978, the group's last full day in the country, Becker became the first American journalist ever to interview the famed Pol Pot. Although she had heard of Brother Number One's charisma, his smile was far more endearing and his manner more polished than she had predicted. But it was not long before he turned off his charm, treating Becker and colleague Dudman as if he had granted them an audience, not an interview. Pol Pot delivered a onehour stinging and paranoid indictment of Vietnam, forecasting a war between NATO and the Warsaw Pact over Cambodia. He warned: "A Kampuchea that is a satellite of Vietnam is a threat and a danger for Southeast Asia and the world ... for Vietnam is already a satellite of the Soviet Union and is carrying out Soviet strategy in Southeast Asia.""' Ironically, as American decisionmakers formed their policy in the coming months, they operated on assumptions that mirrored Pol Pot's.

Caldwell, the Australian ideologue, was granted a separate interview with the supreme revolutionary leader. When he later traded notes with Becker, he delighted in describing Pol Pot's mastery of revolutionary economic theory. Before retiring for the evening, Becker sparred with her zealous colleague one last time about the veracity of refugee accounts, which he still refused to believe, and the worthiness of the revolution, in which he refused to abandon belief. She was awakened in the middle of the night by the sound of tumult and gunfire outside her room. A half dozen or more shots were fired, and an hour and a half of the longest, most terrifying silence of Becker's life passed. When she finally heard the voice of her KR guide, she emerged trembling into the hall. lludman was fine, she was told. Caldwell, the true believer, had been murdered.

Becker did not know why Caldwell had been killed, but she suspected that one faction wanted either to embarrass another or to plug the crack of an opening to the outside world before it widened. A murder would deter meddlesome foreigners from visiting again. On December 23, 1978, Becker and l)udman arrived in Beijing with the wooden casket containing Caldwell's body. Two days later Vietnam launched a full-scale invasion of Cambodia.

Aftermath

"Humanitarian" Rescue

Kassie Neou, one of Cambodia's leading human rights advocates today, survived Pol Pot's madness and the outside world's indifference. An English teacher before the genocide, he posed as a taxi driver, shedding his eyeglasses and working around the clock to develop a "taxi-driver manner" He had to make the KR believe that he had not been educated. Captured nonetheless, Neou was tortured five times and spent six months in a KR prison with thirty-six other inmates. Of the thirty-seven who were bound together with iron clasps, only Neou's hope of survival was rewarded. The young guards executed the others but spared hint because they had grown fond of the Aesop's fables he told them as bedtime stories.When Neou discusses the terror today, he lifts up his trouser leg and displays the whitened, rough skin around his ankle where a manacle held hint in place.The revolutionaries' crimes were so incomprehensible that sonie part of hint seems relieved to be left with tangible proof of his experience.

During his imprisonment, though he had been highly critical of the earlier U.S. involvement in Cambodia, Neou was one of many Cambodians who could not help but dream that the United States would rescue his people. "When you are suffering like we suffered, you simply cannot imagine that nobody will come along to stop the pain;' he remembers. "Everyday, you would wake up and tell yourself, `somebody will come, something is going to happen.' If you stop hoping for rescue, you stop hoping. And hope is all that can keep you alive." Survivors of terror usually recall maintaining similar, necessary illusions. Without them, they say, the temptation to choose death over despair would overwhelm.

Neou had fantasized that the United States would spare him certain death, but it was Vietnam, the enemy of the United States, that in January 1979 finally dislodged the bloody Communist radicals. In response, the United States, which in 1978 had at last begun to condemn the KR, reversed itself, siding with the Cambodian perpetrators of genocide against the Vietnamese aggressors.

Vietnam's invasion had a humanitarian consequence but was not motivated by humanitarian concerns. Indeed, for a long time Vietnam and its Soviet backer had blocked investigation into the atrocities committed by their former partner in revolution. In 1978, however, as KR incursions into Vietnam escalated,Vietnam had begun detailing KR massacres.Vietnamese officials used excerpts from Ponchaud's book, Year Zero, as radio propogan- da. They called on Cambodians to "rise up for the struggle to overthrow the Pol Pot and leng Sary clique" who were "more barbarous ... than the Hitlerite fascists." Vietnam also began reindoctrinating and training Khmer Rouge defectors and Cambodian prisoners seized in territory taken from Cambodia. It crept ever closer to the Soviet Union, joining the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON), signing a twenty-five-year treaty of friendship and cooperation with the Soviets, and receiving ever larger military shipments from them. The Soviet Union Joined Vietnam's anti-KR campaign, condemning the KR "policy of genocide."

For the previous year, the United States had been flirting with restoring relations with Vietnam but was not keen on seeing it overrun its neighbor."' From the U.S. embassy in Bangkok, Ambassador Morton Abramowitz wrote in a secret August 1978 cable to the State Department: "Neither the Khmers nor the world would miss Pol Pot. Nonetheless, the independence of Kampuchea, particularly its freedom from a significant Hanoi presence or complete Hanoi domination, is a matter of importance to us.""' Far from encouraging the overthrow of the KR, as Neou and others would have hoped, U.S. officials urged the Vietnamese to think twice.

In November 1978 Secretary of State Vance sent a message to the Vietnamese: "Don't you see what lies ahead if you invade Cambodia? This is not the way to bring peace to the area. Can't we try some UN instrument, use the UN in some way?"""

The United States had its own reasons for frowning upon a Vietnamese triumph. It planned to restore diplomatic relations with China on January 1, 1979. China's hostility toward Vietnam and its Soviet military and political sponsor greatly influenced the U.S. reaction to the invasion. For neither the first nor the last time, geopolitics trumped genocide. Interests trumped indignation.

Aware of the Khmer Rouge's isolation and unpopularity in the West, Hanoi thought it would earn praise if it overthrew Pol Pot. It also concluded that regardless of the outside world's opinion, it could not afford to allow continued KR encroachments into the Mekong Delta. By December 22, 1978,Vietnamese planes had begun flying forty to fifty sorties per day over Cambodia. And on December 25, 1978, twelve Vietnamese divisions, or some 100,000 Vietnamese troops, retaliated against KR attacks by land. Teaming up with an estimated 20,000 Cambodian insurgents, they rolled swiftly through the Cambodian countryside. Despite U.S. intelligence predictions that the KR would constitute a potent military foe, McGovern's earlier forecast of rapid collapse was borne out. Lacking popular support, the Khmer Rouge and its leaders fled almost immediately to the northern jungle of Cambodia and across the Thai border.

The Vietnamese completed their lightning-speed victory with the seizure of Phnom Penh on January 7, 1979.

Skulls, Bones, and Photos

Upon seizing the country, the Vietnamese found evidence of mass murder everywhere. They were sure this proof would strengthen the legitimacy of their intervention and their puppet rule. In the months and years immediately after the overthrow, journalists who trickled into Cambodia were bombarded by tales of horror. Every neighborhood seemed to unfurl a mass grave of its own. Bones could still be seen protruding from the earth. Anguished citizens personalized the blame. "Pol Pot killed my husband," or "Pol Pot destroyed the temple," they said. Rough numerical estimates of deaths emerged quickly. All told, in the three-and-a-half-year rule of the Khmer Rouge, some 2 million Cambodians out of a populace of 7 million were either executed or starved to death."' National minorities were special targets of the regime. The Vietnamese minority was completely wiped out. Of the 500,000 Muslim Chain who lived in Cambodia before Pol Pot's victory, some 200,000 survived. Of 60,000 Buddhist monks, all but a thousand perished.

The Tuol Sleng Examination Center in Phnom Penh, which was codenamed Office S-21, quickly became the most notorious emblem of the terror."A pair ofVietnamese journalists discovered the center nestled in a part of the capital known as Tuol Svay Prey, or "hillock of the wild mango" While roaming the neighborhood with Vietnamese troops the day after they had seized the capital, they smelled what they thought was rotting flesh and poked their heads into the lush compound that had once served as a girls' high school. They quickly discovered that of the 16,000 Cambodians who had arrived there, only five had departed alive.'''