A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide (32 page)

Read A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide Online

Authors: Samantha Power

Tags: #International Security, #International Relations, #Social Science, #Holocaust, #Violence in Society, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #General, #United States, #Genocide, #Political Science, #History

The Iraqi demolition of villages around Halabja in 1987 had caused the town's population to swell from 40,000 to nearly 80,000. Halabja constituted a special source of irritation and rage for Northern Bureau chief alMajid. Kurdish rebel peshmerga had made it a stronghold of sorts, frequently teaming up with Iranian Revolutionary Guards who seeped across the nearby border. Halabja also lay just seven miles east of a strategically vital source of water for Baghdad.

In mid-March 1988, a joint Kurdish-Iranian operation routed Iraqi soldiers in Halabja. Overnight Iranian soldiers replaced the Iraqis in the border town. Kurdish civilians, the pawns in the struggle between the neighborhood's two big powers, were gripped by a wave of chilling apprehension. On March 16, Iraq counterattacked with deadly gases. "It was different from the other bombs," one witness remembered. "There was a huge sound, a huge flame and it had very destructive ability. If you touched one part of your body that had been burned, your hand burned also. It caused things to catch fire"" The planes flew low enough for the petrified Kurds to take note of the markings, which were those of the Iraqi air force. Many families tumbled into primitive air-raid shelters they had built outside their homes. When the gasses seeped through the cracks, they poured out into the streets in a panic. There they found friends and family members frozen in time like a modern version of Pompeii: slumped a few yards behind a baby carriage, caught permanently holding the hand of a loved one or shielding a child from the poisoned air, or calmly collapsed behind a car steering wheel. Not everybody who was exposed died instantly. Some of those who had inhaled the chemicals continued to stumble around town, blinded by the gas, giggling uncontrollably, or, because their nerves were malfunctioning, buckling at the knees. "People were running through the streets, coughing desperately," one survivor recalled. "I too kept my eyes and mouth covered with a wet cloth and ran.... A little further on we saw an old woman who already lay dead, past help. There was no sign of blood or any injury on her. Her face was waxen and white foam bubbled from the side of her mouth"15 Those who escaped serious exposure fled toward the Iranian border. When reports of the attack reached the outside world, the Iraqi government attributed the assault to Iran.

Halabja quickly became known as the Kurdish Hiroshima. In three days of attacks, victims were exposed to mustard gas, which burns, mutates DNA, and causes malformations and cancer; and the nerve gases sarin and tabun, which can kill, paralyze, or cause immediate and lasting neuropsychiatric damage. Doctors suspect that the dreaded VX gas and the biological agent aflatoxin were also employed. Some 5,000 Kurds were killed immediately. Thousands more were injured. Iraq usually justified its attacks against the Kurds on the grounds that it aimed to destroy the saboteurs aligned with the Iranians. But in Halabja most of the Kurdish peshmerga who had worked with Iran had obtained gas masks. It was unarmed Kurdish civilians who were left helpless.

Halabja was the most notorious and the deadliest single gas attack against the Kurds, but it was one of at least forty chemical assaults ordered by al-Majid. A similar one followed that spring in the village of Guptapa. There, on May 3, 1988, Abdel-Qadir al-'Askari, a chemist, heard a rumor that a chemical attack was imminent. He left the village, which was situated on low ground, and scrambled up a distant hilltop so he might warn his neighbors of imminent danger. When he saw Iraqi planes bombing, he sprinted back down to the village in order to help. But when he reached his home, where he had prepared a makeshift chemical attack shelter, nobody was inside. He remembered:

I became really afraid-convinced that nobody survived. I climbed up from the shelter to a cave nearby, thinking they might have taken refuge there. There was nobody there, either. But when I went to the small stream near our house, I found my mother. She had fallen by the river; her mouth was biting into the mud bank.... I turned my mother over; she was dead. I wanted to kiss her but I knew that if I did, the chemicals would be passed on. Even now I deeply regret not kissing my beloved mother."'

He searched desperately for his wife and children:

I continued along the river. I found the body of my nine-year-old daughter hugging her cousin, who had also choked to death in the water.... Then I went around our house. In the space of 200-300 square meters I saw the bodies of dozens of people from my family. Among them were my children, my brothers, my father, and my nieces and nephews. Some of them were still alive, but I couldn't tell one from the other. I was trying to see if the children were dead. At that point I lost my feelings. I didn't know who to cry for anymore and I didn't know who to go to first. I was all alone at night."

Al-Askari's family contained forty people before the attack and fifteen after. He lost five children-two boys, one sixteen, the other six; and three girls, aged nine, four, and six months. In Guptapa some 150 Kurds were killed in all. Survivors had witnessed the deaths of their friends, their spouses, and their children.

When word of the gas attacks began spreading to other villages, terrified Kurds began fleeing even ahead of the arrival of Iraqi air force bombers. Al-Majid's forces were fairly predictable. Jets began by dropping cluster bombs or chemical cocktails on the targeted villages. Surviving inhabitants fled. When they reached the main roads, Iraqi soldiers and security police rounded them up. They then often looted and firebombed the villages so they could never be reoccupied. Some women and children were sent to their deaths; others were moved to holding pens where many died of starvation and disease.The men were often spirited away and never heard from again. In the zones that Hussein had outlawed, Kurdish life was simply extinct.

Official Skepticism

In Washington skepticism greeted gassing reports. Americans were so hostile toward Iran that they mistrusted Iranian sources. When Iraq had commenced its chemical attacks against the Kurds in early 1987, the two major U.S. papers had carried scattered accounts but had been quick to add that that they were relaying Iranian "allegations" of gassing. Baghdad was said to have "struck back" or "retaliated" against Kurdish rebels." The coverage of Halabja in 1988 was initially similar. The first reports of the attack came from the Islamic Republic News Agency in Teheran, and U.S. news stories again relayed "Iranian accounts" of Iraqi misdeeds. They gave Iraqi officials ample space for denial. Two days after the first attack, a short Washington Post news brief read: "Baghdad has denied reports of fighting. It said it withdrew from Halabja and another town, Khormal, some time ago" "

The Kurds, like many recent victims of genocide, fall into a class of what genocide scholar Helen Fein calls "implicated victims." Although most of the victims of genocide are apolitical civilians, the political or military leaders of a national, ethnic, or religious group often make decisions (to claim basic rights, to stage protests, to launch military revolt, or even to plot terrorist attacks) that give perpetrators an excuse for crackdown and bystanders an excuse to look away. Unlike the Jews of 1930s Europe, who posed no military or even political threat to the territorial integrity of Poland or Germany (given their isolation or assimilation in much of Europe), the Kurds wanted out-out of Hussein's smothering grasp and, in their private confessions, out of his country entirely. Kurds were in fact doubly implicated. Not only did some take up arms and rebel against the Iraqi regime, which was supported by the United States, but some also teamed up with Iran, a U.S. foe. As "guerrillas," the Kurds thus appeared to be inviting repression. And as temporary allies of Iran, they were easily lumped with the very forces responsible for hostage-taking and "Great Satan" berating.

The March 1988 Halabja onslaught did more than any prior attack to draw attention to the civilian toll of Hussein's butchery. In part this was because the loss of some 5,000 civilians made it the deadliest of all the Iraqi chemical assaults. But it was also the accessibility of the scene of the crime that caused outsiders to begin to take notice. Halabja was located just fifteen miles inside Iraq, and Western reporters were able to reach the village wasteland from Iran. They could witness with their own eyes the barbarous residue of what otherwise might have been unimaginable. Reporters had the chance to provide rare, firsthand coverage of a fresh, postgenocidal scene.

Iran, which was still struggling to win its war with Iraq, was eager to present evidence of the war crimes of its nemesis. European and American correspondents visited Iranian hospitals, where they themselves interviewed victims with blotched, peeling skin and labored breathing. The Iranians also offered tours of Halabja, where journalists saw corpses that Iranian soldiers and Kurdish survivors had deliberately delayed burying. The Washington Post and Los Angeles Times ran stories on their front pages on March 24, 1988, and U.S. television networks joined in by prominently covering the story over the next few days. The journalists were aghast, and the dispatches reflected it. Patrick Tyler's Washin,.yon Post story described "the faces of the noncombatant dead: four small girls in traditional dress lying like discarded dolls by a trickling stream below the small hamlet of Anap; two women cuddling in death by a flower garden; an old man in a turban clutching a baby on a door-step""' For the first time, Kurdish faces were on display. They were no longer abstract casualty figures or mere "rebels"

U.S. officials insisted that they could not be sure the Iraqis were responsible for the poisonous gas attacks. Western journalists, who had little experience with Iraq and none with the Kurds, hedged. The disclaimers resurfaced. "More than 100 bodies of women, children and elderly men still lay in the streets, alleys and courtyards of this now-empty city,"Tyler wrote, "victims of what Iran claims is the worst chemical warfare attack on civilians in its 7'/2-year-old war with Iraq."" The NewlbrkTimes March 24 story buried on page Al l was titled, "Iran Charges Iraq with Gas Attack." Newsweek wrote: "Last week the Iranians had a grisly opportunity to make their case when they allowed a few Western reporters to tour Halabja, a city in eastern Iraq recently occupied by Iranian forces after a brief but bloody siege. According to Iran, the Iraqis bombarded the city with chemical weapons after their defeat. The Iranians said the attack killed more than 4,000 civilians ."12 This was not fact; this was argument, and Iranian argument at that. The victims themselves could tell no tales. The journalists were privy to the aftermath of a monstrous crime, but they had not witnessed that crime and refrained from pointing fingers. Thus, the requisite caveats again blunted the power of the revelations.

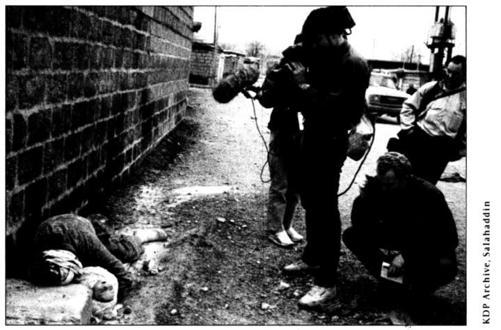

Western journalists filming a Kurdish man and his infant son killed in the March 1988 Iraqi chemical attack on Halabja.

The Iraqis further muddied the waters by leading their own tours of the region. The regime denied the atrocities and reminded outsiders that bad things happen during war. Around the time of Halabja, Iraq's ambassador to France told a news conference: "In a war, no one is there to tell you not to hit below the belt. War is dirty."`Yet "war" also implies two or more sets of combatants, and Hussein's chemical weapons attacks were carried out mainly against Kurdish civilians. But Iraq had its cover: Kurdish rebels had fought alongside Iranians, Iraq was at war with Iran, and the war, everyone knew, was brutal. The fog of war again obscured an act of genocide.

The U.S. official position reflected that of its allies in Europe. But whereas they were almost completely mute about Halabja, the State Department issued a statement that confined its critique to the weapons used. "Everyone in the administration saw the same reports you saw last night," White House spokesman Marlin Fitzwater told reporters. "They were horrible, outrageous, disgusting and should serve as a reminder to all countries of why chemical warfare should be banned""

The United States issued no threats or demands. American outrage was rooted in Hussein's use of deadly chemicals and brazen flouting of the 1925 Geneva Protocol Against Chemical Warfare. The New York Times editorial page condemned the Iraqi gas attack and called upon Washington to suspend support to Baghdad if chemical attacks did not stop. On Capitol Hill Senator George Mitchell (D.-Maine) introduced a forceful Senate resolution decrying Iraqi chemical weapons use. Jim Hoagland of the GiWashin'ton Post condemned Iraq for calling out the "Orkin Squadron" against civilians. Hoagland, who happened to have been with Mullah Mustafa Barzani in the mountains of Kurdistan in March 1975 when the United States abandoned him, now urged America to use all the influence it had been storing up with Hussein to deter further attacks."

Human rights groups were more numerous, more respected, and better financed than they had been during Cambodia's horrors. Helsinki Watch had been established in 1978, and it added Americas Watch in 1981 and Asia Watch in 1985. But it did not have the resources to set up Middle East Watch until 1990. As a result, the organization refrained from public comment on the gassing of Kurds. "We didn't have the expertise," explains Ken Roth, who today directs an organization of more than 200 with an annual budget of nearly $20 million but who was then deputy director of a team of no more than two dozen people. "None of us had been to the region, and we felt we could not get in the business of saying things that we could not follow through on. We would only have raised expectations that there was no way we could meet." Amnesty International had researchers in London who had established contacts with Iraqi Kurds who confirmed the horror of the press reports, but Amnesty staff were unable to enter Iraq. Shorsh Resool, a thirty-year-old Kurdish engineer and Anfal survivor, had never been abroad but wondered why news of the slaughter was never reported on the BBC's Arabic service. He was told that people in the West did not believe the Kurdish claims that 100,000 people had disappeared. The figure sounded abstract and random. Resool resolved to make it concrete. Between October 1988 and October 1999, he walked through northern Iraq, dodging Iraqi troop patrols and systematically interviewing tens of thousands of Anfal survivors. He assembled a list of names of 16,482 Kurds who had gone missing. When he extrapolated his statistical survey, he concluded that between 70,000 and 100,000 Kurds had in fact been murdered. But when he presented this evidence to the Amnesty researcher in London, she asked, "Do you really expect people to believe that that many Kurds could disappear in a year without anybody knowing about it?"