A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide (29 page)

Read A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide Online

Authors: Samantha Power

Tags: #International Security, #International Relations, #Social Science, #Holocaust, #Violence in Society, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #General, #United States, #Genocide, #Political Science, #History

Although Proxmire believed that ratification of the genocide ban would spur Senate ratification of other human rights treaties such as the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights; the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women; the Convention on the Rights of the Child; and later the international treaty to ban land mines, none has passed.

On October 19, 1988, Proxmire stood up in a deserted Senate chamber to speak about the genocide convention one last time. He noted that the belated Senate passage had prompted New York Times columnist A. M. Rosenthal, the man whom Lemkin had hounded in the late 1940s and early 1950s at the United Nations, to write a column entitled, "A Man Called Lemkin" Proxmire, then seventy-two, rose a little more slowly than he had twenty-one years before, when he had pledged to carry forward Lemkin's crusade. Proxmire requested that Rosenthal's article be published in the Congressional Record. "It is a tribute to a remarkable man named Raphael Lemkin," Proxmire said, "one individual who made the great difference against virtually impossible odds.... Lemkin died 29 years ago.... He was a great man""

With the Reagan administration's support, the U.S. Senate had finally ratified the genocide convention. But when the president and the Senate got their first chance to enforce the law, strategic and domestic political concerns caused them to side with the genocidal regime of Saddam Hussein. Far from making the United States more likely to do more to stop genocide, ratification seemed only to make U.S. officials more cautious about using the term.

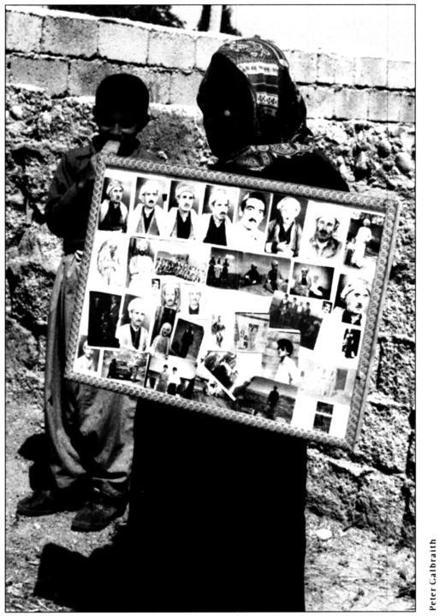

A Kurdish widow holding up photographs of family members 'disappeared" by Iraqi forces.

Chapter 8

Iraq: "Human Rights

and Chemical

Weapons Use Aside"

In March 1987, a year after the U.S. Senate ratified the genocide convention, Iraqi president Saddam Hussein appointed his cousin All Hassan alMajid as secretary-general of the Northern Bureau, one of five administrative zones in Iraq.The Iraqi dictator vested in al-Majid supreme authority. "Comrade al-Majid's decisions shall be mandatory for all state agencies, be they military, civilian [or] security" Hussein declared. The new Northern Bureau chief set out to use these absolute powers, in his words, to "solve the Kurdish problem and slaughter the saboteurs."'

Ever since Iraq had gone to war with Iran in 1980, Hussein had been especially concerned about his "Kurdish problem." Kurds made up more than 4 million of Iraq's population of 18 million. Although Hussein's security forces could control those in the towns, Baghdad found it difficult to keep a close watch on rural areas inhabited by Kurds. Armed Kurds used the shelter of the mountains to stage rebellions against Iraqi forces. Some even aligned themselves with Iran. Hussein decided that the best way to stamp out rebellion was to stamp out Kurdish life.

Al-Majid ordered Kurds to move out of the homes they had inhabited for centuries and into collective centers, where the state would be able to monitor them. Any Kurd who remained in the so-called "prohibited zones" and refused to resettle in the new government housing complexes would henceforth be considered a traitor and marked for extinction. Iraqi special police and regulars carried out al-Majid's master plan, cleansing, gassing, and killing with bureaucratic precision. The Iraqi offensive began in 1987 and peaked between February and September 1988 in what was known as the Anfal campaign. Translated as "the spoils," the Arabic term a1 fal conies from the eighth sura of the Koran, which describes Muhammad's revelation in 624 C.E. after routing a band of nonbelievers. The revelation announced: "He that defies God and His apostle shall be sternly punished by God. We said to them: `Taste this. The scourge of the Fire awaits the unbelievers."' Hussein had decreed that the Kurds of Iraq would be met by the scourge of Iraqi forces. Kurdish villages and everything inside became the "spoils," the booty from the Iraqi military operation. Acting on Hussein's wishes, and upon al-Majid's explicit commands, Iraqi soldiers plundered or destroyed everything in sight. In eight consecutive, carefully coordinated waves of the Anfal, they wiped out (or "Saddamized") Kurdish life in rural Iraq.

Although the offensive was billed as a counter-insurgency mission, armed Kurdish rebels were by no means the only targets. Saddam Hussein aimed his offensive at every man, woman, and child who resided in the new no-go areas. And the Kurdish men who were rounded up were killed not in the heat of battle or while they posed a military threat to the regime. Instead, they were bussed in groups to remote areas, where they were machine-gunned in planned mass executions.

Hussein did not set out to exterminate every last Kurd in Iraq, as Hitler had tried against the Jews. Nor did he order all the educated to be murdered, as Pol Pot had done. In fact, Kurds in Iraq's cities were terrorized no more than the the rest of Iraq's petrified citizenry. Genocide was probably not even Hussein's primary objective. His main aim was to eliminate the Kurdish insurgency. But it was clear at the time and has become even clearer since that the destruction of Iraq's rural Kurdish population was the means he chose to end that rebellion. Kurdish civilians were rounded up and executed or gassed not because of anything they as individuals did but simply because they were Kurds.

In 1987-1988 Saddam Hussein's forces destroyed several thousand Iraqi Kurdish villages and hamlets and killed close to 100,000 Iraqi Kurds, nearly all of whom were unarmed and many of whom were women and children. Although intelligence and press reports of Iraqi brutality against the Kurds surfaced almost immediately, U.S. policymakers and Western journalists treated Iraqi violence as if it were an understandable attempt to suppress rebellion or a grisly collateral consequence of the Iran-Iraq war. Since the United States had chosen to back Iraq in that war, it refrained from protest, denied it had conclusive proof of Iraqi chemical weapons use, and insisted that Saddam Hussein would eventually come around. It was not until September 1988 that the flight of tens of thousands of Kurds into Turkey forced the United States to condemn the regime for using poisonous gas against its own people. Still, although it finally deplored chemical weapons attacks, the Washington establishment deemed Hussein's broader campaign of destruction, like Pol Pot's a decade before and Turkey's back in 1915, an "internal affair."

Between 1983 and 1988, the United States had supplied Iraq with more than $500 million per year in credits so it could purchase American farm products under a program called the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC). After the September 1988 attack, Senator Claiborne Pell introduced a sanctions package on Capitol Hill that would have cut off agricultural and manufacturing credits to Hussein as punishment for his killing of unarmed civilians. Influenced by his foreign policy aide Peter Galbraith, Pell argued that not even a U.S. ally could get away with gassing his own people. But the Bush administration, instead of suspending the CCC program or any of the other perks extended to the Iraqi regime, in 1989, a year after Hussein's savage gassing attacks and deportations had been documented, doubled its commitment to Iraq, hiking annual CCC credits above $1 billion. Pell's Prevention of Genocide Act, which would have penalized Hussein, was torpedoed.

Despite its recent ratification of the genocide convention, when the opportunity arose for the United States to send a strong message that genocide would not be tolerated-that the destruction of Iraq's rural Kurdish populace would have to stop-special interests, economic profit, and a geopolitical tilt toward Iraq thwarted humanitarian concerns. The Reagan administration punted on genocide, and the Kurds (and later the United States) paid the price.

Warning

Background: No Friends but the Mountains

The Kurds are a stateless people scattered over Turkey, Iran, Syria, and Iraq. Some 25 million Kurds cover an estimated 200,000 square miles. The Kurds are divided by two forms of Islam, five borders, and three Kurdish languages and alphabets. The major powers promised them a state of their own in 1922, but when Turkey refused to ratify the Treaty of Sevres (the same moribund pact that would have required prosecution of Turks for their atrocities against the Armenians), the idea was dropped. Iraqi Kurds staged frequent rebellions throughout the century in the hopes of winning the right to govern themselves. With a restless Shiite community comprising more than half of Iraq's population, Hussein was particularly determined to neutralize the Kurds' demands for autonomy.

The Kurdish fighters adopted the name peshrnerqa, or "those who face death." They have tended to face death alone. Western nations that have allied with them have betrayed them whenever a more strategically profitable prospect has emerged. The Kurds thus like to say that they "have no friends but the mountains.-

U.S. policymakers have long found the Iraqi Kurds an infuriating bunch. The Kurds have been innocent of desiring any harm to the Iraqi people, but like Albanians in Kosovo throughout the 1990s, they were guilty of demanding autonomy for themselves. Haywood Rankin, a Middle East specialist at the U.S. embassy in Baghdad, made a point of visiting Kurdish territory several times each year. "You have to understand," Rankin says. "The Kurds are a terribly irksome, difficult people. They can't get along with one another, never mind with anybody else. They are truly impossible, an absolute nightmare to deal with."

Through decades of suffering and war, Iraqi Kurds have not just had to worry about repressive rule and wayward allies; they have had to keep one eye on each other. They have squabbled and indeed even warred with one another as often as they have attempted to wriggle free of their Baghdad masters. Washui,'toti Post correspondent Jonathan Randal dubbed the rivalry between Kurdish Democratic Party (KI)P) leader Massoud Barzani and Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) leader Jalal Talabani as the Middle Eastern version of the Hatfields and the McCoys. As Randal wrote and as many U.S. foreign policymakers would agree, "Kurdistan exists as much despite as because of the Kurds"'

Iraq's most violent campaign against the rural Kurds, which began in 1987 and accelerated with the Anfal in 1988, was new in scale and precision, but it was the most forceful manifestation of a long-standing effort by Iraq to repress the Kurds. In 1970 Iraq offered the Kurds significant selfrule in a Kurdistan Autonomous Region that covered only half of the territory Kurds considered theirs and that excluded Kurdish-populated oil-rich provinces. After the Kurds rejected the offer, Saddam Hussein imposed the plan unilaterally in 1974. The Kurds trusted they would receive support from Iran, Israel, and the United States (which was uneasy about Iraq's recent friendship treaty with the Soviet Union), and they revolted under their legendary leader Mullah Mustafa Barzani (the grandfather of Massoud). In 1975, however, with U.S. backing, Iran and Iraq concluded the Algiers agreement, temporarily settling a historic border dispute: Iraq agreed to recognize the Iranian position on the border, and the shah of Iran and the United States withdrew their support for the Kurds. Betrayed, Barzani's revolt promptly collapsed. Henry Kissinger, U.S. secretary of state at the time, said of the American reversal of policy and the Kurds' reversal of fortune, "Covert action should not be confused with missionary work"' For his part, Saddam Hussein publicly warned, "Those who have sold themselves to the foreigner will not escape punishment"' He exacted swift revenge.

Hussein promptly ordered the 4,000 square miles of Kurdish territory in northern Iraq Arabized. He diluted mixed-race districts by importing large Arab communities and required that Kurds leave any areas he deemed strategically valuable. Beginning in 1975 and continuing intermittently through the late 1970s, the Iraqis established a 6-12-mile-wide "prohibited zone" along their border with Iran. Iraqi forces destroyed every village that fell inside the zone and relocated Kurdish inhabitants to the mujamma'at, large army-controlled collective settlements along the main highways in the interior.Tens of thousands of Kurds were deported to southern Iraq. In light of how much more severe Hussein would later treat the Kurds, this phase of repression seems relatively mild: The Iraqi government offered compensation, and local Kurdish political and religious leaders usually smoothed the relocation, arriving ahead of the Iraqi army and its bulldozers and guns. In addition, many of the Kurdish men who were deported to the Iraqi deserts actually returned alive several years later. Still, the evacuations took their toll. According to the Ba'ath Party newspaper A1-Tliau'ra ("The Revolution"), 28,000 families (as many as 200,000 people) were deported from the border area in just two months in the summer of 1978. Kurdish sources say nearly half a million Kurds were resettled in the late 1970s.'

When Iraq went to war with Iran in 1980, the Kurds' prospects further plummeted. The war began after Iraq turned its back on the 1975 Algiers agreement that had briefly settled its border dispute with Iran. In reviving its claim to the entire Shatt al-Arab waterway, Iraq wanted to demonstrate to the new regime of the Ayatollah Khomeini that it was the regional strongman. It also wished to signal its displeasure with Iran for continuing to support Kurdish rebels in Iraq. Iran's Khomeini in turn began urging Iraqi Shiites to rise up against Hussein. Iraq countered by pledging to support Iranian rebel movements. Border skirmishes commenced. In April 1979 Iraq executed the leading Shiite clergyman, Ayatollah Muhammad Bakr al-Sadr. And on September 4, 1980, Iran began shelling Iraqi border towns.To this day, when Iraqis celebrate the war, they mark its beginning as September 4. But it was not until September 22 that Iraq launched a strike into the oil-rich Iranian province of Khuzistan. Hussein expected that the Iranian defenses would crumble instantly. For neither the first nor the last time, the Iraqi dictator miscalculated. Caught off-guard by the invasion and still reeling from the revolution, Iran did founder at the start, in part because the ayatollah had destroyed the shah's professional military. But Iran bounced back and counterattacked in what would become one of the most bloody, futile wars of the twentieth century-a war that gave Saddam pretext, motivation, and cover to target Iraq's Kurdish minority.