A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide (72 page)

Read A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide Online

Authors: Samantha Power

Tags: #International Security, #International Relations, #Social Science, #Holocaust, #Violence in Society, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #General, #United States, #Genocide, #Political Science, #History

The humiliation associated with the fall of Srebrenica ate at Clinton. The occurrence of such savagery in the heart of Europe made him look weak. For the first time, he believed that events in Bosnia might impede other coveted aims. One of Clinton's senior advisers remembers, "This issue had become a cancer on our foreign policy and on his administration's leadership. It had become clear that continued failure in Bosnia was going to spill over and damage the rest of our domestic and foreign policy." Clinton saw that the United States had to make its own decisions. Passivity in the face of Bosnian Serb aggression was no longer a viable policy option.

In these turbulent July days, Clinton often sounded more moved by the damage the fall of Srebrenica was doing to his presidency than by its effect on the lives of defenseless Muslims. On the evening of July 14, the president, who was on the White House putting green, received a briefing from Sandy Berger and Nancy Soderberg, his numbers two and three on the National Security Council. He recognized that he was finally in danger of paying a political price for nonintervention. In a forty-five-minute rant strewn with profanities, Clinton said, "This can't continue.... We have to seize control of this.... I'm getting creamed!""

At the July 18 meeting where Vice President Gore alluded to the young woman who had hanged herself, Clinton said he backed the use of robust airpower, declaring, "The United States can't be a punching bag in the world anymore."" The discussion, though influenced by an awareness of genocide, was rooted in politics first and foremost. Srebrenica was gone; Zepa would soon follow. Clinton had to stop the cycle of humiliation.

U.S. inaction reflected so poorly on the president that even Dick Morris, Clinton's pollster, lobbied for bombing. Morris later recalled that "Bosnia had become a metaphor for Clintonian weakness." He was surprised by Clinton's attitude. "I found that every time I discussed Bosnia with the president, we ran into this word can't over and over again," Morris remembered. "'What do you mean can't?' I said in one meeting.'You're the commander in chief, where does can't come from?"'"'

Endgame

With the Clinton presidency implicated, the Bosnian war had to be stopped. Back in June, National Security Adviser Lake had urged Clinton's cabinet members to decide what they wanted a reconstituted Bosnia to look like and work backward. Lake had been trying to get the foreign policy team to think strategically so they did not get perpetually bogged down in crisis management. On July 17 Lake finally unveiled his "endgame strategy" at a breakfast meeting of the foreign policy team. The United States would take over the diplomatic show and back its diplomacy by threatening to bomb the Serbs and lift the embargo." President Clinton took the unusual step of dropping in on the meeting. Clinton said he opposed the status quo. "The policy is doing enormous damage to the United States and our standing in the world. We look weak," he said, predicting it would only get worse. "The only time we've ever made progress is when we geared up NATO to pose a real threat to the Serbs.""

Time was short. On July 26, 1995, the U.S. Senate had passed the DoleLieberman bill to end U.S. compliance with the embargo. On August 1 the House of Representatives followed suit, authorizing the lift by a veto-proof margin. The Serbs had begun amassing troops around the safe area of Bihac. Clinton and Lake agreed the time had come to inform the Europeans of the new U.S. policy. They were able to use Dole's embargo legislation as leverage in order to "lay out the marching orders." In a marked contrast with earlier periods in the war and with their complete neglect of the Rwanda genocide, the president's national security advisers met twenty-one times between July 17 and Lake's August 8 departure for Europe. The president joined them in meetings on August 2, 7, and 8."" With the clock ticking, they recognized it was time for a "full-court press." Unlike Secretary Christopher's May 1993 trip, in which he offered a tepid sales pitch on behalf of Clinton's "lift and strike" policy, Lake laid out a version of that policy by saying to the Europeans, in effect,"This is what we're prepared to do if there is no settlement. This is what we intend to do. We hope you'll come with us""'

Many on the Clinton team were still nervous about of the use of force. Memories of the Vietnam War made Lake and the U.S. military planners especially fearful of open-ended commitments. But senior U.S. officials were emboldened by a new development in the Balkans. Croatia, which had been occupied by rebel Serbs since its war of independence in 1991, had launched an offensive aimed at reconquering lost territory and expelling members of its Serb minority. At the time Lake was unveiling America's "endgame," the Croatian army was sweeping through Serb-held territory in Croatia and western Bosnia. Croatia's success showed that the so-called Serb juggernaut was more of a paper tiger, a vital piece of news for those who had deferred for years to alarmist Pentagon warnings of steep U.S. casualties. It also showed, crucially, that Serbian president Slobidan Milosevic was prepeared to stand back and allow Serbs in neighboring Croatia and Bosnia to be overrun. If NATO intervened, it would face only the Bosnian Serbs, not the Yugoslav National Army.

A number of Western negotiators were secretly relieved that the Serbs had taken Srebrenica and Zepa because the loss of the two Muslim enclaves had tidied the map of Bosnia by eliminating two nettlesome noncontiguous patches of territory. A peace deal seemed easier to reach and, once reached, easier to enforce. And Western diplomats had at last come to the slow realization that they were negotiating not with gentlemen but with evil. Military force was the only answer.

The full-court press produced an immediate turnover. At the July conference of Western leaders, the United States had secured a commitment to bomb the Serbs if they attacked the Gorazde safe area. In the coming weeks Lake, Holbrooke, and others pressed successfully to extend NATO's protective umbrella to three other safe areas-Bihac, Tuzla, and Sarajevo. One of the "keys" that needed to be turned before air strikes could be launched was removed from the hands of the gun-shy civilian head of the UN mission, Akashi, and placed in the hands of UN force commander Janvier, which at least left two generals in charge. More important, Washington and its European allies understood that the next time NATO bombed, it could not launch only pinpricks and it could not allow Serb hostage-taking to diminish allied resolve. UN peacekeepers were withdrawn from Serb territory in late August, where they were achieving almost nothing besides serving as potential hostages.

On August 14, 1995, Secretary Christopher had given Assistant Secretary Holbrooke command over U.S. diplomacy on Bosnia. On August 19 Holbrooke's five-man negotiating team drove over Mount Igman into Sarajevo. The Sarajevo airport had been shut down by Serb shelling, and the Serbs had refused to guarantee the safety of international flights. As a result, the U.S. delegation had no choice but to drive its bulky vehicles along the perilous mountain road that had been widened unsatisfactorily to accommodate Bosnian truck drivers bringing goods into the city. A UN armored personnel carrier transporting part of the U.S. delegation slipped off the road and tumbled down the mountain. Three of Holbrooke's colleagues and friends, Nelson Drew, Robert Frasure, and Joseph Kruzel, were killed. This was the first time American officials had died in the Balkan wars. Holbrooke brought the bodies back to the United States, flying part of the way with his knees wedged up against one of the coffins. The tragedy further energized the new diplomatic effort and heightened U.S. determination to end the war. "For the first time in the entire conflict, we took deaths," Holbrooke says."And these were the deaths of three treasured senior public servants and friends. Everyone was torn apart. Suddenly, the war had come home."

On August 28, 1995, a shell landed near the very same Sarajevo market where sixty-eight people had been killed in February 1994. This time the Serb attack killed thirty-seven and wounded eighty-eight. From Paris, Holbrooke called Washington, frantic. Clinton, Gore, Christopher, Perry, and Lake were all away on vacation. Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott asked Holbrooke what he wanted to recommend to Christopher and Clinton. "Call us the negotiation team for bombing," Holbrooke said. "We've got to bomb."

And at last NATO did. Beginning on August 30, 1995, and continuing consistently for the next three weeks, NATO planes flew 3,400 sorties and 750 attack missions against fifty-six targets. They avoided aged and rusty Serb tanks and concentrated on ammunition bunkers, surface-to-air missile sites, and communications centers. They called the mission Operation Deliberate Force, as if to announce up front that what might have been called "Operation Halfhearted Force" was a thing of the past. The Bosnian Serb army was sent into a tailspin, and Muslim and Croat soldiers succeeded in retaking some 20 percent of the country that had been seized and cleansed in 1992.When Lake got word that the planes were raining bombs upon the Serb positions, he phoned the president, who was in Wyoming.

"Whoooppeee!" Clinton whispered, confirming, as Congressman Frank McCloskey had told him the year before, that bombing the Serb military did make him feel good."2

Backed by the newly credible threat of military force, the United States was easily able to convince the Serbs to stop shelling civilians. In November 1995, the Clinton administration brokered a peace accord in Dayton, Ohio.The agreement left Serbs, 31 percent of the population, with 49 percent of the land. Croats, who made up 17 percent of the population, received 25 percent, and the Muslims, who constituted 44 percent, were allocated just 25 percent. Three ethnically "pure" slivers of territory were almost all that were left of Bosnia.The three groups were kept together in a single country, but under an extremely weak central government. More than 200,000 people had been killed since the war began in April 1992. One out of two people had lost their homes. In December 1995, speaking from the Oval Office, President Clinton movingly invoked the massacres in Srebrenica and the recent killings in the Sarajevo marketplace to justify the deployment of 20,000 U.S. troops to Bosnia.

Although the war was over, Clinton had a small problem. Ever since his administration had abandoned its lift-and-strike policy proposal in May 1993, senior officials had been arguing that Bosnia constituted "a problem from hell." They had said that intervention would be futile or would imperil U.S. interests. It would thus be difficult for those same officials now to retract their earlier rhetoric and convince the American people of the sudden worthiness of contributing troops to enforce the Dayton peace. Entering an election year, the Republican leadership on Capitol Hill was poised to strike.

Several of Clinton's Republican challengers did try to score points, telling the public that Bosnia was not worth a single American life. But Clinton's presidential challenger, Senator Dole, closed ranks behind the commander in chief. In the late fall, Dole teamed up with Senator John McCain, the Arizona Republican and fellow war hero. The pair publicly backed the president's decision to deploy U.S. troops to Bosnia. Dole and McCain knew that their Republican colleagues would be upset by their refusal to attack Clinton. Dole's campaign managers in New Hampshire told him, "You already got problems.You don't need this!" Dole tried to head off some of the intra-party criticism by calling a meeting with a dozen angry Republican senators. McCain remembered the session. "The rhetoric was intense and emotional: `Don't put our boys in harm's way.' `Body bags.' All that," McCain said. "They were just pounding us.... I was getting more and more depressed"When the meeting finally ended and the Republican critics filed out into the hall, the Arizona senator despaired. But as McCain walked out with Dole, who had said almost nothing, the majority leader cheerily observed, "Makin' progress!" As bad as it had been, Dole had expected it to be much worse.' In the end Dole helped convert twentyeight Republicans to Clinton's cause. The Senate approved the deployment of U.S. troops to Bosnia by 60 votes in favor, 39 opposed.

Clinton knew significant casualties would harm his prospects in November. "The conventional political wisdom," he said, was that there was "no upside and tons of downside" to the U.S. deployment. But he was willing to risk it: "You have to ask yourself which decision would you rather defend ten years from now when you're not in office" Clinton said. "I would rather explain why we tried" than why "NATO's alliance was destroyed, and the influence of the United States was compromised for ten years.."" For the first time, Clinton saw the costs of noninvolvement as greater than the risks of involvement.

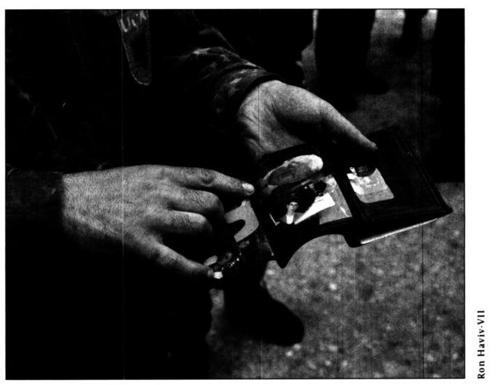

President Clinton defeated Senator Dole handily in 1996.A year later, in November 1997, Clinton appointed his former challenger chairman of the International Commission on Missing Persons, which had been established to locate some of the 40,000 still missing from the wars in the former Yugoslavia, including the more than 7,000 who disappeared from Srebrenica. The Balkan commission funded the collection of forensic data, DNA identification, and the de-mining of grave sites. Upon accepting the chairmanship, Dole delivered some brief remarks. "Some may question and some do question why we're involved in Bosnia in the first place," Dole said. "I think that's a very easy answer: because we happen to be the leader of the world""