A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide (68 page)

Read A Problem From Hell: America and the Age of Genocide Online

Authors: Samantha Power

Tags: #International Security, #International Relations, #Social Science, #Holocaust, #Violence in Society, #20th Century, #Political Freedom & Security, #General, #United States, #Genocide, #Political Science, #History

In 1993 President Clinton had appointed Peter Galbraith as U.S. ambassador to Croatia. Galbraith's heroics in northern Iraq in 1991 had earned him plaudits from the influential senators Al Gore and Daniel Patrick Moynihan. At the time of the seizure of Srebrenica, Galbraith happened again to be back in Vermont, where he had read the New York Times story about the gassing of the Kurds seven years before. Like Holbrooke, Galbraith had visited Bosnia, including the Manjaca concentration camp, in 1992. He had int-°rviewed Muslim refugees and survivors for the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and had recommended using NATO airpower to stop Serb aggression. Galbraith was now incredulous that the United States could be allowing the fall of the safe area, the deportation of more than 20,000 Muslim women and children, and the detention and possible execution of the Muslim men. On the basis of his experience with Cambodians and Kurds, he quickly surmised that the men in Mladic's custody had already been murdered. "People don't just disappear," he recalls. "Once we didn't hear from them and once we couldn't get access to the area, we knew. How could we not know?" He says he spent much of that week on the phone with Assistant Secretary Holbrooke. Both men spoke of resigning out of despair over the U.S. response to the safe area's fall. Holbrooke arranged a meeting for Galbraith with Secretary of State Christopher on Jul), 17, the first one-on-one meeting Galbraith had ever been granted with the secretary, who made his dislike for the outspoken ambassador known. Galbraith feared that neither Srebrenica's land nor Srebrenica's Muslim men could be saved. He did not believe that he had a prayer of convincing Christopher to roll back Serb gains. But he spoke out against the massacres because he did believe that credible U.S. threats of bombing were still needed to save Muslims in the nearby safe area of Zepa, which Mladic had begun attacking on July 14 and which was guarded by just seventy-nine peacekeepers. Galbraith met with a stone wall. Christopher and virtually all other U.S. officials were already convinced that Zepa could not be saved. It was, they said,"indefensible."Action would be futile.

The following day Vice President Al Gore, another of the administration's longtime proponents of bombing, joined the high-level conversation. He said he believed events in Bosnia constituted genocide. "The worst solution would be to acquiesce to genocide and allow the rape of another city and more refugees," Gore said in a Clinton cabinet meeting. "We can't be driven by images, because there's plenty of other places that aren't being photographed where terrible things are going on," Gore acknowledged. Nonetheless, he added, "We can't ignore the images either" The cause of consistency could not be allowed to defeat that of humanity.

The Washington Post's John Pomfret had just filed an arresting report on the atrocities from Tuzla.The piece began:

The young woman died with no shoes on. Sometime Thursday night she climbed a high tree near the muddy ditch where she had camped for 36 hours. Knotting a shabby floral shawl together with her belt, she secured it to a branch, ran her head of black hair through the makeshift noose and jumped.... She had no relatives with her and sobbed by herself until the moment she scaled the tree."'

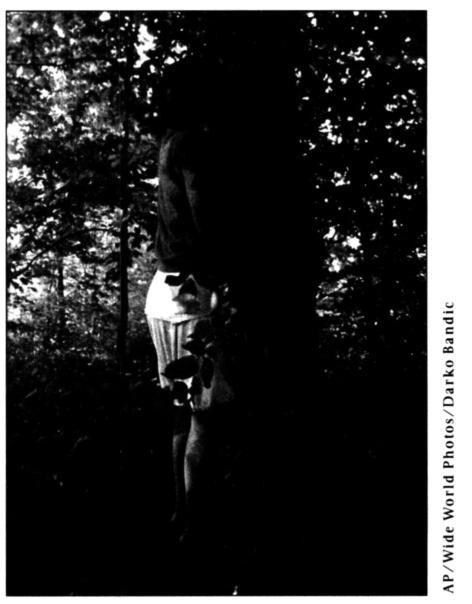

Gore told the Clinton cabinet that in the photo that accompanied Pomfret's story, the woman looked around the same age as his daughter. "My twenty-one-year-old daughter asked about that picture," Gore said. "What am I supposed to tell her? Why is this happening and we're not doing anything?" Srebrenica provided Gore, Albright, and Holbrooke with an opening to restart the conversation about NATO bombing. Although Gore gave every appearance of challenging the president, witnesses say his remarks were in fact less geared to convert Clinton than they were aimed at senior officials in the Pentagon, who remained unconvinced of the utility of using airpower. "My daughter is surprised the world is allowing this to happen," Gore said, pausing for effect. "I am too" Clinton said the United States would take action and agreed, in Gore's words, that "acquiescence is not an option.""

A Muslim refugee from Srebrenica who hanged herself in despair. The woman, who was in her early twenties, was found hanging by a torn blanket at the Tuzla air base on July 14, 1995.

On July 19, in a confidential memorandum Assistant Secretary for Hunan Rights Shattuck delivered a preliminary account of the Serb abuses and argued that the other safe areas should be protected:

The human rights abuses we are seeing hearken back to the very worst, early days of "ethnic cleansing." In Bratunac [a town near Srebrenica], 4,000-5,200 nien and boys are incarcerated and the Bosnian Serbs continue to deny access to them. Another 3,000 soldiers died as they fled Srebrenica, some taking their own lives rather than risking falling into Serb hands. There are credible reports of summary executions and the kidnapping and rape of Bosnian women. 12

Shattuck urged the protection of the remaining safe areas, arguing that the Muslims in Bosnia's safe areas had relied on the "international conununitv's promise," which was "clear, proper and well-considered " He argued that a failure to act would mean not only the fall of the safe areas but a UN withdrawal. If the Europeans pulled out their peacekeepers, the United States would have to follow through on prior pledges to assist in their evacuation. This would be messy and humiliating. Shattuck warned, "U.S. troops will be on the ground helping the UN force pull out while Bosnian Serbs ... fire upon them, and fearful Muslim civilians try to block their exit." This was the image that most haunted U.S. policymakers, and Shattuck hoped the threat of bloody U.S. involvement down the road would tip the balance in favor of immediate intervention.

The most detailed early evidence of the Bosnian Serbs' crimes came on July 20, 1995, when three Muslim male survivors staggered out of the woods with the bullet wounds to prove what to that point had simply been feared: Mladic was systematically executing the men in his custody.

A lack of food, water, and sleep and a surfeit of terror had left the men delirious. But they told their stories first to Bosnian Muslim police and then to Western journalists. Each account defied belief. Each survivor had prayed and assumed that his experience had not been shared by others. There were uncanny parallels in the killing tactics described at three different sites. Some massacres took place two by two; others twenty by twenty. The men were ordered to sit on buses or in warehouses as they waited their turn. One man remembered the night of July 13, which he spent on a bus outside a school in Bratunac.The Serbs pulled people off the buses for summary execution. "All night long we heard gunshots and moaning coming from the direction of the school," the man said. "That was probably the worst experi- ence,just sitting in the bus all night hearing the gunfire and the human cries and not knowing what will happen to you" He was relieved the following morning when a white UN vehicle pulled up. But when the four men dressed as UN soldiers delivered the Serb salute and spoke fluent Serbian, he realized his hoped-for rescuers were in fact Serb reinforcements who had stolen Dutch uniforms and armored personnel carriers."

At the Grbavici school gym, several thousand men were gathered and ordered to strip down to their underwear. They were loaded in groups of twenty-five onto trucks, which delivered them to execution sites. Some of the men pulled off their blindfolds and saw that the meadow they approached was strewn with dead Muslim men. One eyewitness, who survived by hiding under dead bodies, described his ordeal:

They took us off a truck in twos and led us out into some kind of meadow. People started taking off blindfolds and yelling in fear because the meadow was littered with corpses. I was put in the front row, but I fell over to the left before the first shots were fired so that bodies fell on top of me. They were shooting at us ... from all different directions. About an hour later I looked tip and saw dead bodies everywhere. They were bringing in more trucks with more people to be executed. After a bulldozer driver walked away, I crawled over the dead bodies and into the forest.`a

The Serbs marched hundreds of Muslim prisoners toward the town of Kravica and herded them into a large warehouse. Serb soldiers positioned themselves at the warehouse's windows and doorways and fired their rifles and rocket-propelled grenades and threw hand grenades into the building, where the men were trapped. Shrapnel and bullets ripped into the flesh of those inside, leaving emblazoned upon the walls a montage of crimson and gray that no amount of scrubbing could remove. The soldiers finished off those still twitching and left a warehouse full of corpses to be bulldozed."

Kemarkably, Muslim survivors of the massacre continued to hope. Only hours after Serb soldiers had shot up the warehouse and its human contents, one Serb returned and shouted, "Is anyone alive in there? Come out.You're going to be loaded onto a truck and become part of our army" Several men got up, believing.The Serbs returned again a while later, this time promising an ambulance for the wounded. Again, survivors rose and left the warehouse. One Kravica survivor who laid low and eventually escaped remembers his shock at the credulity of his peers. He also remembers his own disappointment on hearing successive rounds of gunshots outside."'

Graves

On July 21, 1995, the allied leaders gathered in London for an emergency conference meant to iron out a new Bosnia policy. The Zepa enclave still hung in the balance, and the evil in Srebrenica had been broadly publicized. But the allies stunned Bosnia's Muslims by issuing what became known as the London declaration. The declaration threatened "substantial and decisive air-power," but only in response to Serb attacks on the safe area of Gorazde, one of the few Bosnian safe areas not then under fire.The declaration did not mention Sarajevo, which continued to withstand fierce artillery siege; Zepa, which had not yet fallen; or the men of Srebrenica, some of whom were still alive.

A convoy of Dutch peacekeepers departed Srebrenica the same day. They arrived to a heroes' welcome at UN headquarters in Zagreb. At a press conference the Dutch defense minister announced that the Dutch had seen Muslims led away and heard shooting. He also said they had heard that some 1,600 Muslims were killed in a local schoolyard. The rumors, he said, were too numerous and "too authentic" to be false. Yet this was the first the Dutch had spoken publicly about their suspicions. Moreover, apart from the defense minister's grim reference, he presented a relatively mild general picture. He complained that the Serbs were still denying the Red Cross access to some 6,000 Muslim prisoners. When the dazed Dutch commander Karremans spoke, he praised Mladic for his "excellently planned military operation" and reflected that "the parties in Bosnia cannot be divided into `the good guys' and `the bad guys. "' That night at a festive UN headquarters in Zagreb, the Dutch drank and danced well into the early morning.

On July 24 the UN special rapporteur for human rights for the former Yugoslavia, onetime Polish prime minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki, described the findings of his week-long investigation. He said 7,000 of Srebrenica's 40,000 residents seemed to have "disappeared." He appealed to the Western powers to ensure that Zepa's 16,000 residents not meet the same fate. Zepa's Muslim defenders continued to hang on, even though the UN had already announced that it would not summon air strikes to aid their defense."

On July 27, 1995, Mazowiecki announced his resignation. He was sickened by the UN refusal to stand up to the Serbs in Srebrenica and Zepa. In his resignation letter, he wrote:

One cannot speak about the protection of human rights with credibility when one is confronted with the lack of consistency and courage displayed by the international community and its leaders.... Crimes have been committed with swiftness and brutality and by contrast the response of the international community has been slow and ineffectual.... The very stability of international order and the principle of civilization is at stake over the question of Bosnia. I am not convinced that the turning point hoped for will happen and cannot continue to participate in the pretense of the protection of human rights.''

When Galbraith returned to his post in Croatia, he received even more damning news about the Srebrenica men. His fiancee, a UN political officer, happened to be in Tuzla, where she overheard a UN interview with one of the male survivors of a mass execution. On July 25, 1995, Galbraith sent Secretary Christopher a highly classified, "No Distribution" cable headed, "Possible Mass Execution of Srebrenica Males Is Reason to Save Zepa":

1. A UN official has recounted to me an interview she conducted of a Srebrenica refugee in Tuzla. The account, which she felt was highly credible, provides disturbing evidence that the Bosnian Serbs have massacred many, if not most, of the 5,000 plus military age men in their custody following the fall of Srebrenica.

2. If the Bosnian Serb army massacred the defenders of Srebrenica, we can be sure a similar fate awaits many of the 16,000 people in Zepa.The London Declaration implicitly writes off Zepa. In view of the numerous accounts of atrocities in Srebrenica and the possibility of a major massacre there, I urge reconsideration of air strikes to help Zepa... .