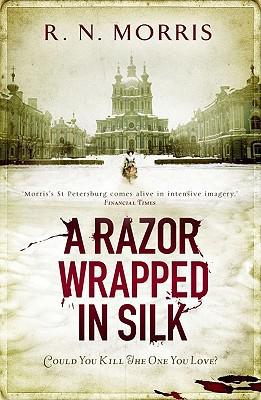

A Razor Wrapped in Silk

A

RAZOR

WRAPPED

IN

SILK

A St Petersburg Mystery

R. N. Morris

For Gillian and Don

‘I am convinced that hidden in his drawer is a razor, wrapped in silk, like that murderer in Moscow; he too lived

in the same house with his mother and had wrapped a razor in silk to cut a throat with.’

From

The Idiot

by Fyodor Dostoevsky (translation by Henry Carlisle and Olga Andreyev Carlisle)

Contents

2 An encounter with a gendarme

4 A scene at the Naryskin Palace

6 White camellias, a red thread, and seven rings

22 The school over the workshop

28 A representative of the Third Section

30 The dead come back to murder

36 Captain Mizinchikov’s confession

Mitka looked up. He saw the high ceiling of the spinning-shop through a haze of cotton dust scored with countless lines of yarn. The dust was white, like snow but finer. It hung in the hot air, beneath the turning shafts that spanned the workshop and drove the machines. Incessantly moving, yet going nowhere, they held him entranced with a vision of infinity, presented as unrelenting monotony.

He could always taste the dust, always feel it, on him and in him, smothering him. Even in his parched dreams, even in the best of them, when he dreamt of her, and the great feeling took him over – even then, she came to him through a shifting white mist and fed him sweetmeats that tasted of cotton. And in those dreams, the throbbing noise that drowned out her tender words was the chiming clatter of the machines.

Was he dreaming now?

The thought frightened him into a state of strained alertness.

He was crouched within the great jaws of the spinning mule. The mule itself, the movable frame which carried over a thousand spindles, or so Mr Ustyantsev claimed, was edging away from the fixed part of the machine. It drew the unspun rovings of cotton from the creel and stretched the fibres into the finest of prison bars. It was Mitka’s job to watch for broken threads and tie up the ends, conspiring in his own imprisonment. Once the mule had completed its outward carriage, it would

begin its return, walked home by Mr Ustyantsev as it wound in the threads it had spun. Mitka knew of children who, in falling asleep, had been caught in its inexorable bite, unseen by the machine operator. If they were lucky they’d lose a finger, ripped off in the blink of an eye. The hobgoblins and ogres of fairytales were nothing compared to the lurking terrors of the factory. His heart raced, like the bobbins on a double-speeder. He thought of Anya, the girl who had fallen into the driving belt. It had carried her round three times before they had managed to get her out, her screams mingling with the routine screech of metal. In the English foreman’s arms, her body hung as limp as a sack of rags. Word got round later that every bone in her body had been broken. Mitka could never forgive Beck for the look on his face as he held her: a look devoid of pity or grief, showing only the contempt of an inconvenienced man. Anya had been ten years old, the same age as Mitka, and a foundling like him. This had been enough to bind them together, like two weak and ragged threads. Their friendship had not developed much beyond silent sympathetic glances and the occasional stolen word. But her eyes had always been the first he sought in the sting of any injustice.

Mitka craned his neck back to scan the taut threads over his head. Every muscle was tense and aching. He winced sharply as a spasm of cramp gripped his right calf. He longed to stand and straighten the leg, but couldn’t, not yet at least. He closed his eyes over the pain. It could only have been for a moment, but it was a moment in which he allowed himself to luxuriate in the dangerous dream of lying stretched out on the hard floor beneath the cotton canopy.

He opened his eyes in panic. To his relief, he was still locked in his tight little squat. A thread had snapped while he had

dozed. The loose ends trailed on the floor, one drawn away from him by the moving mule, the other gathering into a loose spiral as the rollers spewed more thread. Mitka moved quickly, tying the ends with dextrous fingers, taking secret pride in the speed with which he accomplished the task.

There was a clank as the mule reached the end of its track, followed by a whirring and grinding of gears as the machine adjusted to the next phase of the operation. Mitka grabbed the hand brush and swept the floor ahead of him as he retreated.

Out in the open, in the seemingly limitless expanse of the spinning-shop, there was just time to stand and stretch, to roll his shoulders and kick the cramp out of his leg, before he had to run round and duck into the now opening jaws of the machine opposite.

Bent into position once more, Mitka looked up at the haze of cotton dust scored with countless lines.

*

The steam whistle’s blast announced the end of the shift. Mitka scurried out of his daily prison, as fast as a venting of pressure.

He came out into a choking fog that seemed, in the first shock, to be an extension of the cotton haze he had just escaped. But the air was cooler here, and the particles it bore, black and hard-grained. In the spinning-shop they kept the air hot as well as humid, for the sake of the cotton. The change of temperature set his teeth chattering. He had on a cap but no coat; was still dressed only in the clothes he worked in, the ragged cotton shirt, and drill trousers tucked into his boots.

Night was coming on and the lamps in the yard were lit. The dark, soot-laden fog absorbed any light it could and held it in a stifled glow.

It was unusually quiet for the end of a shift: disembodied footsteps, but no voices, apart from an occasional murmur or exhausted sigh. It was as if the fog sealed each individual worker off in a wad of solitude.

But the fog served Mitka’s purposes. It would make it easier to slip past Granny Kvasova, who was even now waiting to shepherd the foundling children into the apprentice house. The thought of a place by the stove and a share of the communal bowl tempted him. But once inside the house there would be no escape. The door was locked on the children as soon as they stepped through it. He would miss that evening’s class. He would not see

her

.

He called her Mother. All the children called her Mother, even the ones who had mothers of their own. Even the adult workers who attended the Free School called her Little Mother. She was the sweetest, kindest, most beautiful mother any of them could imagine.

She fed them dreams and hope, food for their souls not their bellies. He would gladly forego Granny Kvasova’s cabbage soup for a smile from his Nourishing Mother. It was her image that sustained him beneath the immense veil of threads each day; the thought that he would see her, sit at her feet with the others as she told them the story of The Dead Princess and the Seven Knights, or taught them the words to

Kalinka

.

Mitka felt the towering presence of the Nevsky Cotton-Spinning Factory behind him. He did not look back. In the fog, its gigantic mass would be transformed into a vague, premonitory shadow of itself. But he knew that the blackened bricks were there, the filthy chimneys, the grimy windows, and he could not bear to turn his face in their direction, to acknowledge their hold over him with even a glance. Hated as

it was, it pulled at him, like a weight of sorrow to which he was chained. He wanted to run from it.

Suddenly a soft orb of light appeared ahead of him, swaying high in the air. Someone had raised a lantern on a pole. He could see the flattened, drained form of Granny Kvasova and hear her croaking shout: ‘Children, this way! Children! Granny’s here!’ In his exhaustion, he almost walked towards the summoning, drawn by habit, like a mechanised part returning to its housing. But now the fog was on his side. It gave him time to think, or at least to remember the Mother waiting for him in the schoolroom.

He gave the lantern a wide berth and left the old woman’s cries behind.

A whiff of pipe smoke conjured forth the image of Uncle Pyotr, the gatekeeper. Portly and sly, he pretended to be a friend to the children, bestowing winks as if they were sugar crystals. But there was something about his eyes that Mitka never trusted, a cold watchfulness that belied his empty joviality. He had them call him uncle, though he was no more their uncle than the old Kvasova woman was their granny. The man’s wheezing cough and high, almost falsetto voice sounded startlingly close, signalling both the way out and a final trap. If Uncle Pyotr caught him he was bound to hand him over to Granny Kvasova. Mitka would then have to plead to be allowed to go to school. She would inevitably deny him, while Uncle Pyotr chuckled as if it was all a joke. No doubt she would use the fog as an excuse, but the real reason would be because she sensed how much he wanted it. He had heard her arguments before, the same ones, more or less, retailed by Mr Ustyantsev: ‘It will do you no good, filling your head with geography and nonsense. All you need to learn, young lad, is your place.’

But Mitka knew the place assigned for him only too well: between the yawning jaws of the spinning mule, beneath the cotton strands.

The gatekeeper appeared isolated by the choking blanket of grey. His bulky form came and went, like a figure in a nightmare, an embodiment of fear, partially glimpsed. Uncle Pyotr was warming his hands over a brazier, his greatcoat buttoned up against the raw air. He was sharing a joke with some of the men.

Mitka held back, so as not to be seen. But then he heard the heavy clomp of bark shoes, coming up behind him. Stepping to one side, he peered through the fog as a new group of men came into view. Judging by their grubby peasant shirts and kaftans, not to mention their wild beards and crude haircuts, they were unskilled workers, not long up from the country. There was a burst of sharp, unpleasant laughter as they drew level with the huddle at the gate. Mitka followed in their wake and ducked behind them, clearing the factory yard.

He could hear Uncle Pyotr teasing the country bumpkins: ‘Careful you don’t fall in the river, you lads. Mind, with those boats on your feet, you’ll probably walk to the other side!’

His cronies provided a chorus of appreciative braying. Their smart, almost dandified city clothes, glimpsed by Mitka as he dashed past, marked them out as spinners.

The bleat of a barge’s foghorn sounded from the nearby Bolshaia Neva. Mitka could smell the river and hear its lapping water, but not see it. It would be straight ahead of him. With Uncle Pyotr’s facetious warning in mind, he turned sharply to the right.

He saw the glow of a street lamp ahead of him.

The boy experienced a giddy sense of liberation as he walked.

It was as if the fog had not merely masked but obliterated the factory. Softly, silently, and with infinite stealth, it had conjured away the great evil that loomed so high over his life, and weighed so heavily upon it.