A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy (15 page)

Read A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy Online

Authors: Thomas J. Cutler

On the great flat deck of this largest of combatants was the smallest of airfields. In the faint illumination of subdued flight-deck lighting, hundreds of Sailorsâwhose average age was a mere nineteen and a half yearsâwent about their duties as though it were any other day of routine flight operations. Yellow-shirted petty officers waved their light wands to direct tractor-drivers in blue shirts as they repositioned F-14 Tomcats and F-18 Hornets, while brown-shirted plane captains perched in the cockpits rode the aircraft brakes. Purple-shirted Sailors wrestled with snakelike fuel hoses, while others in green prepared the steam-hissing catapults. Beneath the wings and fuselages of the attack aircraft, aviation ordnancemen in red shirts hoisted the bombs and missiles into the waiting latches on the undersides of the airplanes.

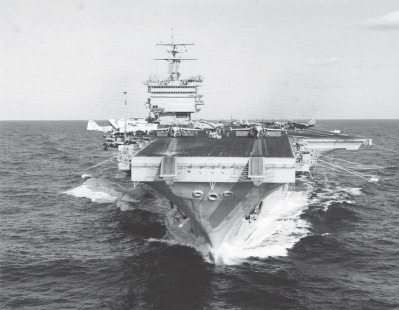

The nuclear-powered aircraft carrier USS

Enterprise

was among the first Navy ships to strike at terrorists in Afghanistan after the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on 11 September 2001.

U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

As one of the 500-pound bombs rolled off an ordnance elevator, a young airman pulled a piece of chalk from his pocket and, with a wide smile on his soot-smeared face, scrawled across the side of the weapon, “Hijack this!” A red-shirted chief petty officer squatting beneath a nearby aircraft, his weathered features contorted into a scowl, carefully wrote the letters “NYPD” on one side of a Mark 83 bomb and “FDNY” on the other, in tribute to the courage of other uniformed men and women who had raced into the stricken World Trade Center towers, heedless of the great danger that would soon take their lives. “It's payback time,” he said, slapping the side of the olive-colored bomb.

The date was 7 October 2001, and Operation Enduring Freedom was about to begin. Several weeks before, “Big E”âas

Enterprise

Sailors called their shipâhad just completed a six-month deployment and, on 9 September, had headed for home. With her crew happily anticipating the joyous homecoming, she had barely begun the long trek across the Atlantic Ocean when news of the 9/11 terrorist attacks stunned the world. In what will long be remembered as the famous “

Enterprise

U-turn,” the ship's captain, without waiting for orders from higher authority, turned the carrier around and headed back for the troubled part of the world that had spawned the terrorist attacks.

Aviation ordnancemen hoisting precision-guided munitions to the wing pylon of an aircraft that will soon launch and take the war to the enemy.

U.S. Navy (Philip A. McDaniel)

The feelings of many of

Enterprise

's Sailors at the time were summed up well by a young third class gunner's mate from Brooklyn when he told a reporter: “I was ready to go home, but I felt I needed to go back and get whoever was responsible for this. From my building I can see all of Manhattan. When I go home and see the big empty space [where the World Trade Center towers used to be], it will really hit me.”

Now, in conjunction with other U.S. and allied ships,

Enterprise

was about to launch air strikes into Afghanistan, a dark corner of the world with a tragic history recently made worse by an oppressive regime known as the Taliban. These Islamic extremists ruled with an iron fist, severely punishing nonbelievers, denying basic rights to women, and keeping the general populace in a state of fear, ignorance, and deplorable poverty. Not only had this oppressive regime done much to hurt the image of Islam, they also had provided sanctuary to some of the world's nastiest terrorists. The Taliban had permitted al Qaeda and other radical groups to set up terrorist training

camps in the desolate areas of the region, and they had provided a haven for the likes of Osama bin Laden, acknowledged perpetrator of the 9/11 attacks and alleged mastermind behind the terrorist attacks on American embassies and the destroyer

Cole.

In the aftermath of the 9/11 tragedy, the obvious first target in the newly declared War on Terrorism was Afghanistan.

As the hour approached for the air strikes to commence, more off-duty Sailors than usual joined the reporters who lined the railing of the observation area known as “Vulture's Row.” Some of these Sailors had come out merely to get some air before reporting to watch stations somewhere below decks, where night and day were indistinguishable and the only air that flowed came from man-made ventilators. Others had come to Vulture's Row because they sensed that history was being made, and they wanted to witness it with their own eyes. But most were there because it somehow felt like the right thing to do, as though their collective presence might breathe an extra measure of vitality into the coming launch, might somehow help lift those lethal machines into the air, and might speed them on their way to seek vengeance for a terrible wrong. More than one reporter noted that the faces of these Sailors were set with grim determination as they watched the aircraft taxi up to the catapults amidst the deafening whine of powerful jet engines and the pungent odor of JP5 fuel thick in the night air.

There was no wild cheering as the first aircraft rocketed down the catapult track and roared into the black sky. There were no high fives as, one after another, Hornets and Tomcats took to the air and headed for the enemy's territory far to the north. Instead, there was an almost palpable sense of relief as the observers felt the dissipation of the feeling of helplessness that had gripped them since they first stared, horrified, at television screens, watching airliners full of innocent people forced to crash into buildings full of more innocent people. Unlike the vast majority of Americans who could do little more than seethe or grieve, the men and women of USS

Enterprise

were striking back. And as many would attest, it felt very good indeed.

Had this been a training exercise in friendlier waters, the strike aircraft from

Enterprise

would have to have flown from the Gulf of Mexico to the Great Lakes region to travel a distance equivalent to that being flown this night. Refueled twice by combinations of Navy S-3 Vikings and Air Force tankers on the way to their targets, the Big E's aircraft reached Afghanistan while the rugged mountains and barren deserts were still enshrouded in darkness. The American fliers rained down bombs, missiles, and rockets on terrorist training camps, airfields, weapons storage areas, and Taliban troop concentrations. Although subjected to antiaircraft fire in various forms, not a single aircraft was lost in the raids, not a drop of American blood was

shed. But as the aircraft turned southward for the long return trip, they left behind an assortment of smoldering remains, signaling the coming demise of the Taliban and the beginning of the end for al Qaeda.

Six hours after their launch, Big E's brood returned safely to the nest. Again, there were no overt celebrationsâsimply a strong sense of accomplishment and a realization that this was just the beginning. Indeed, as the crews from this first sortie headed for a belated breakfast and much-needed rest, other sorties were shuttling to and from enemy targets, keeping the pressure on.

Over the next several weeks,

Enterprise

's Sailors displayed the courage needed to carry out their commitment to defend their nation with honor as they ran sortie after sortie into Afghanistan. Along with other ships in the task force, they hammered away at the enemy, keeping him on the run, breaking down his infrastructure, making him pay for his terrible deeds, teaching him that an angered America is a formidable foe indeed. Big E's attack aircraft flew the length and breadth of Afghanistan, from Kabul to Kandahar to Jalalabad to Herat to Mazar-e-Sharif. They struck at the Taliban's military academy, artillery garrisons, radar installations, and surface-to-air missile sites. They rained fire and destruction down on mountaintops and guided precision weapons into cave entrances. They attacked terrorists attempting to flee by SUV and by camel. They maintained safe zones where C-17 aircraft could deliver food, clothing, and medical supplies to long-suffering Afghanis. By the time

Enterprise

was released to go home, her mission planners were having difficulty finding meaningful targets.

On 13 October, six days after the initial strike, Big E's crew paused briefly to celebrate the U.S. Navy's birthday. As they shared ice cream and cake especially prepared for the occasion, the ship's captain told the crew: “Two hundred and twenty-six years ago we were fighting the British for our freedom. Today it's the same thing. We're fighting for freedom from terrorism.”

When the captain spoke of the struggle for freedom 226 years earlier, he might also have told the Big E's crew that the

Enterprise

had been there too. Obviously, she was not the nuclear-powered giant that had struck at Afghanistan. She was the first of

eight

American naval ships to carry that name. She was involved in the first American naval attack in history and would subsequently play a role in one of the most strategically important battles of the American Revolution.

When the American colonies revolted against royal authority in 1775, Great Britain had a tremendous advantage over its rebellious subjects

because the Royal Navy was the most powerful in the world. This was particularly significant because travel along the eastern seaboard of America, from New England to the South, was easier by sea than by land. Relatively few bridges spanned the many rivers that flowed through the colonies, making it much easier for troops to be moved from place to place by ship than by road.

The Americans, by contrast, had

no

navy at all. George Washington, Commander in Chief of the American Army, and John Adams, one of the more influential members of the Continental Congress, were among those who recognized the importance of having a navy, but it would be some time before the Americans could put together even a small naval capability. In May 1775, however, not even a month after the first shots of the Revolution had been fired at Lexington and Concord, a series of events began that would bring about two significant naval engagements that would have far-reaching effects.

Both the American colonists and their British adversaries recognized the importance of the string of waterways in the wilderness north of New York City that led down from Canada into the very heart of the rebellious American colonies. From the St. Lawrence River in Canada, a natural invasion route followed the Richelieu River, Lake Champlain, Lake George, and the Hudson River. If the British could control this water highway, they could effectively cut off the New England colonies from the rest, making their ultimate subjugation a much simpler matter.

Recognizing this strategic vulnerability, an American force led by Colonel Ethan Allen and Colonel Benedict Arnold captured Fort Ticonderoga at the southern end of Lake Champlain. Arnold, who would later become infamous for betraying the American cause, was, in the early days of the Revolution, one of the ablest of American commanders. The capture of the British fort was significant because it not only blocked a British invasion from the north but also provided much-needed cannon and gunpowder that would be used in the siege of Boston.

Learning that the British had a ten-gun sloop of war named

George

at a place called St. Johns at the northern end of the lake, Arnold feared that this vesselâthe largest on the lakeâcould bring down enough Redcoats to recapture Ticonderoga. Therefore, he decided that the best way to prevent this would be to capture the British sloop.

Although a colonel in the newly formed Continental Army, Benedict Arnold had spent much of his earlier life at sea and was a capable mariner. He devised a plan and sent some of his men farther south to Skenesboro to bring back a small schooner named

Katherine.

Arnold later wrote that upon the little schooner's arrival, “We immediately fixed her with four carriage

guns and six swivel guns.” The Americans then cut gun ports in her sides and practiced running the carriage guns out with block and tackle rigs until they were proficient. They renamed the small warship

Liberty

and, along with two thirty-three-foot boats armed with swivel guns along their gunwales and one larger gun in the bow, the Americans got under way and headed north.