A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy (36 page)

Read A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy Online

Authors: Thomas J. Cutler

Battleship

Texas

had taken the more aggressive move of turning to port,

toward

the Spanish ships. But the turning

Brooklyn

had crossed right into her path, causing

Texas

to back her engines to avoid a collision. This initial tactical confusion had given the Spanish ships a head start, and for a time it seemed they might escape.

But the U.S. ships were faster once they got up a good head of steam. Soon they had closed to gun range and commenced firing. A running gun-fight lasted for several hours.

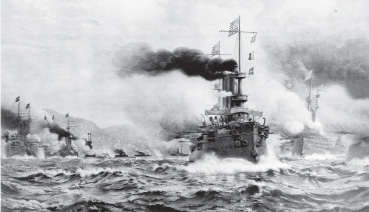

U.S. and Spanish ships slug it out during the Battle of Santiago Bay in July 1898.

U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

The crews of the U.S. ships were better trained and had their adversaries out-gunned.

Maria Teresa

was the first ship to succumb. Numerous shells struck her, one of which severed her fire mains, making it impossible for her crew to fight the spreading fires and forcing her to flood her magazines to prevent a fatal explosion. Burning and sinking, she struck her colors at 1015.

The other Spanish ships suffered similar fates. The destroyers had been the last to emerge from Santiago Bay and succumbed to the deadly fire of the gunboat

Gloucester

and the cruiser

Indiana

before they could launch their torpedoes as planned. American gunners pounded the other Spanish cruisers into submission, and, one by one, the Spanish put their rudders over to starboard and deliberately ran aground on the Cuban shore to avoid sinking.

Only

Cristóbal Colón

was able to escape the devastating onslaughtâfor a time. She was the fastest Spanish ship and, spurred on by frequent shots of brandy, her stokers were able to pour on coal fast enough to keep her out of range of her pursuers. But by 1300 the stokers were unquestionably exhausted (and probably drunk), and shells from

Oregon

and

Brooklyn

began to find their marks.

Cristóbal Colón

could not endure the pounding long, and soon her captain struck her colors and she too headed for the nearby shore to ground herself.

The American strategy had paid off. The Spanish threat in the Atlantic had been eliminated and, coupled with some important land actions, the war was over in little more than a month. Spanish casualties at Santiago had been in the hundreds. The U.S. Navy had lost one killed and one wounded. Victory led to the end of Spanish rule in Cuba, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico and set the stage for America's role as a world power in the coming twentieth century.

As we have seen, strategy has much to do with the outcome of a war. But wars are not won without battles. And battles are not often won without superior tactics. While strategy is in the hands of a relative fewâusually admirals and commodoresâtactical decisions must be made by many and, therefore, must often be made by Sailors of much lesser rank. John Paul Jones, revered as the father of the U.S. Navy, was a mere lieutenant when he defeated the much superior HMS

Serapis

in his most famous battle. James Elliott Williams was a first class petty officer when he earned the Medal of Honor by defeating an entire regiment of North Vietnamese soldiers with just the two patrol craft under his command.

A Spanish ship in the aftermath of the Battle of Santiago Bay. Spanish casualties were in the hundreds; the U.S. Navy lost one killed and one wounded.

U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

Tactics and courage often go hand in hand. Both Jones and Williams used superior tactics to achieve their victories, but the tactical decisions they made could not have been carried out without a great deal of courage on their part and on the part of the men fighting with them. In one of the great tactical victories of all time, known as the Battle of Samar, U.S. ships caused a powerful Japanese fleetâwhich included several battleships and a super battleshipâto turn back without striking their intended target, the vulnerable amphibious forces on the beaches of Leyte Island. Yet the ships who accomplished this great feat were a handful of destroyers and destroyer escorts with little hope of survival, much less victoryâtruly a tactical triumph bought with an incredible amount of courage!

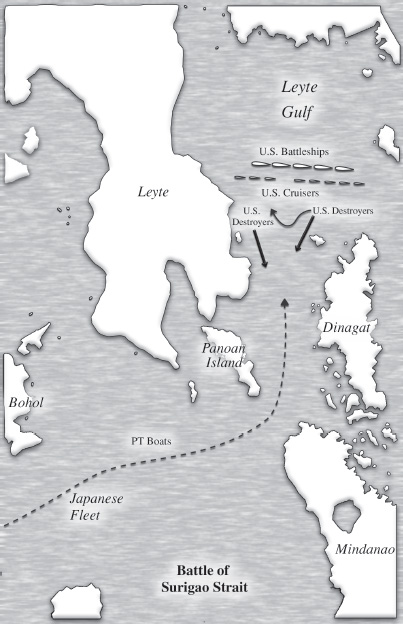

In that same 1944 campaign in Leyte Gulf, another battle had taken place the night before, and this one (described in

chapter 5

) was marked by superb tactics on the part of the Americans. Another Japanese force was approaching the landing area from a different direction, coming up from the south through a narrow passage among the Philippine Islands known as Surigao Strait. This force of battleships, cruisers, and destroyers came under the cover of darkness, a good tactical decision because the force had no air cover. Had they been able to penetrate Leyte Gulf from the south as planned, the Japanese could have inflicted serious damage on the U.S. landing

forces arrayed there. But the Americans, commanded by Rear Admiral Jesse Oldendorf, knew the Japanese were coming and had planned their tactics masterfully.

Because the Japanese would be confined to the narrow strait as they approached, they would have to come in a column formation and would have little maneuvering room. Oldendorf capitalized on this by placing the battleships and cruisers at the north end of the strait, out in the more open waters of the gulf, where they had room to maneuver and to form a line blocking the exit from the strait. This employed a naval tactic as old as sea warfare itself, called

crossing the T.

With the Japanese column forming the base of the T, and the American force capping it, the U.S. ships would be showing their sides to the Japanese ships' bows. This meant the Americans could bring all their guns to bear by training them to one side, while the Japanese could fire only their forward mounts straight ahead. Even worse for the Japanese, when the battle commenced, only ships near the head of the column would be in range so that they alone could fire, while all of the U.S. ships could fire broadsides at once.

Taking further advantage of his geographic position, Oldendorf arrayed his destroyers along either side of the northern end of the strait in such a way as to allow them to charge down the sides of the narrow passage, using the darkness and smokescreens as cover, to launch torpedo attacks at the Japanese flanks.

The plan worked beautifully. Warned of the Japanese approach by PT boats that Oldendorf had placed at the south end of the strait, the U.S. forces at the northern end were ready when the Japanese arrived. American destroyers led the attack using just their torpedoes, knowing that muzzle flashes from their guns would reveal their positions to the enemy. These “tin cans” inflicted serious damage on the approaching enemy. Then the lead Japanese ships took another beating as they came within range of the line of battleships and cruisers blocking the northern end of the strait.

To make matters worse, the Japanese commander made a serious tactical blunder when, deciding that retreat was his best option, he used a corpen maneuver instead of a turn. The former required his ships to maintain the order of the column and turn much as a railroad train wouldâengine first, followed by each car in successionâwhich meant that each ship would move into range of the U.S. battleships and cruisers who were raining down death and destruction. Had the Japanese commander used a turn instead of a corpen, all of the Japanese ships would have turned simultaneously, reversing the order of the column and exiting much more efficiently and safely.

A Japanese destroyer was the first to be sunk. Then battleship

Fuso

was literally blown in two, each half burning furiously and lighting up the strait like beacons in the night. More Japanese ships succumbed as the battle continued, until barely one badly damaged destroyer was able to escape. When dawn illuminated Surigao Strait, the remains of a powerful Japanese naval force littered the waters. It was a temporary monument to a one-sided victory for the U.S. Navy rarely equaled in history.

From the northern end of Surigao Strait, U.S. battleships and cruisers fired on the approaching Japanese fleet that was trying to attack the landing forces in Leyte Gulf. American destroyers charged down into the narrow waterway in the dark of night to launch their torpedoes.

U.S. Naval Institute staff

In the Spanish-American War, World War II, and many other times in U.S. naval history, good tactics supporting good strategy were key components in the final outcomes. But from the foregoing examples, it should be evident that there is more to the equation of victory. The war words

strategy

and

tactics

are rightfully associated with the human brain. But three other words are every bit as essential to victory in war, and they are more appropriately associated with the heart and the soul of the American Sailorâhonor, courage, and commitment. These attributesâmaintained as guiding principles at all times, whether the nation is at peace or at war, and coupled with the right strategy and tactics when hostilities become necessaryâhave resulted in a long record of achievement that has not only earned the U.S. Navy an enviable reputation, but also has played an indispensable role in preserving the freedom of this great nation.

| Strange but True | 9 |

Morgan Robertson once wrote a novel titled

Futility.

It was not particularly good literature, but it did have one unusual characteristic that almost defies the imagination.

It told the story of a fictitious ship, a cruise liner Robertson vividly fabricated, that was the very cutting edge of technology, considered unsinkable and therefore carrying too few lifeboats for her passengers and crew. In the novel, this ship gets under way for her maiden voyage and, on a cold April night, strikes an iceberg and is lost.

Many will quickly recognize the similarity between this tale and the true story of the sinking of the

Titanic.

She too struck an iceberg on her maiden voyage on a cold April night. She too was considered unsinkable and carried too few lifeboats. Both ships had three screws and two masts. Both were rated to carry three thousand passengers. Both vessels struck icebergs on their starboard sides. Robertson's fictitious ship was 800 feet long, had nineteen watertight compartments, and was making 25 knots when she struck the iceberg.

Titanic

was 882.5 feet long, had sixteen watertight compartments, and was making 22.5 knots when she actually struck the iceberg.

One might think Robertson was stealing his story line except for the amazing fact that he wrote his story in 1898 and

Titanic

did not sail until 1912! And if all of those coincidences were not enough, one final fact is that Robertson had named his imaginary ship

Titan.

Sailors are known as a superstitious lot. Through the centuries, many legends have become part of nautical lore. The

Flying Dutchman

is said to roam the seven seas with a ghost crew, the appearance of dolphins in a ship's bow wave when she is departing on a cruise is said to be a harbinger of good luck, and whistling aboard ship was once believed to create storms or headwinds. While these beliefs are no more real than bad luck occurring on Friday the thirteenth, there are times when occurrences are difficult to dismiss as mere coincidence. And a few of those coincidences are part of the history of the U.S. Navy.