A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy (32 page)

Read A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy Online

Authors: Thomas J. Cutler

Vernon Highfill heard the word passed to leave the engine room, but he soon realized that his intended escape route was blocked. Then he remembered the narrow space that ran between the main tube and the outside skin of the stack. Through choking smoke, Highfill made his way to that space and squeezed in. Climbing upward as quickly as he could, he soon emerged into the open air at the top of the stack. Climbing down from the stack, he “saw a hole in the flight deck big enough to put a house in.” Exhausted, he dropped to the deck and marveled at being alive.

But it was now apparent that Lady Lex would

not

live. With the ship dead in the water and fires raging out of control, Captain Sherman reluctantly gave the order that no captain ever wants to give: “Abandon ship.”

To the inexperienced and the uninformed, the act of abandoning ship probably conjures up visions of men simply jumping over the side or climbing down lines to lifeboats. But that would be simply “every man for himself.” To be sure, when ships are in their death throes and panic is lurking close at hand, there are those who do just that. But on

Lexington

at this dark moment, a higher calling prevailed for many of her crew. Because the general announcing system was no longer functioning, many Sailors had not gotten the word to leave the ship. Still manning their stations, they were in grave danger of being left behind. Others were injured or overcome by heat and smoke. In the “shipmate” tradition that is as old as seafaring itself,

Lexington

Sailors returned to the hell raging inside the ship to find buddies and strangers. At great risk to themselves, those who were able-bodied carried their injured shipmates through dark, debris-laden, smoke-filled passageways. As they got the wounded to relative safety, many again went back into the chaos below to find others who might be trapped and lead them to safety as well. A young mess steward made repeated trips despite the second-degree burns he suffered each time he went back. One Sailor saw the executive officer, Commander Seligman, “continually being blown through doors and out of scuttles like a cork out of a champagne bottle” as he kept hunting for men still lost below. In the radio shack, would-be rescuers burst in, ready to assist those in need, only to find a young radioman busily cleaning the dust off the now-dormant radio sets.

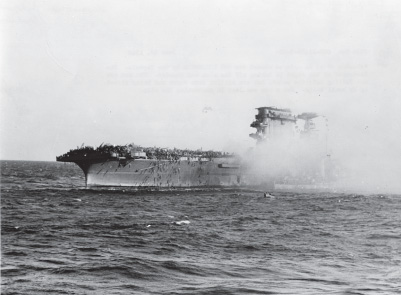

Sailors from USS

Lexington

abandon ship during the Battle of the Coral Sea during World War II.

U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

Knotted lines, cargo nets, and bedsheets tied together were suspended from the flight and hangar decks, and men were streaming down them in good order. Others jumped or dove as though they were back at their home-town swimming holes.

In a few hours, Fireman Highfill, Commander Seligman, the dusting radioman, and hundreds of other men were crowded onto escort ships, watching the final moments of their ship. In the gathering darkness, the burning ship lit the sea and sky. Exploding ammunition and aircraft fuel tanks periodically flared like some great fireworks display.

Admiral Frank Fletcher, the officer in tactical command, worried that

Lexington

would serve as a beacon to aid the enemy in locating his fleet, so he made the painful decision to send her to the bottom as quickly as possible. He ordered one of the destroyers to torpedo her and then ordered the task force to depart the area.

Lady Lex did not give up easily as multiple torpedoes bit into her sides, but eventually she settled quietly into the sea just as the evening watch was being set on the surviving ships. The great fires winked out until all was dark as nature intended. Then there was a final explosion that was felt on the departing ships miles away, and

Lexington

plunged to the bottom of the Coral Sea.

In writing his official report, Captain Sherman recorded that 216 men of a total complement of 2,951 had been lost with the ship. He added that both the ship and the crew had “performed gloriously.” He also noted that

Lexington

's demise was “more fitting than the usual fate of the eventual scrap heap or succumbing to the perils of the sea.”

The Battle of the Coral Sea was over. As the Japanese and American forces withdrew from these waters, the fighting had temporarily ended, but the reckoning had just begun. Each side had scored victories; both had suffered losses. For those who had perished, the war was over, but for those whose task it remained to fight on, there was a long road of struggle and sacrifice ahead. One of the tasks of the living was to determine the significance of this first major battle and to decide how to take best advantage of it. As events would prove, it would be the U.S. Navy who would do the better job.

Like most specialized subjects, warfare has a vocabulary of its own. The word

logistics,

for example, describes an element of warfare that is often overlooked by the casual observer but absolutely essential to the achievement of victory. Logistics is supplying forces with the crucial things they need to fight effectivelyâfood, fuel, clothing, ammunition, repair parts, and so forth. Another term,

metrics,

has more recently entered the vocabulary of war and describes those elementsânumbers of casualties and rounds expended, for exampleâby which effectiveness is measured. But among those specialized words,

strategy

and

tactics

âterms often used to describe the planning, the classifying, and the differentiating of various actions and their significance in warâare among the most frequently used, yet their meanings are often not fully understood by those who use them. For example, the Battle of the Coral Sea in World War II is often described as a

strategic

victory for the U.S. Navy and a

tactical

victory for the Japanese. But what does that mean?

Although these terms are similar and overlap in their meanings, there are notable differences, nevertheless, that are valuable when plans for wars and battles are made and those engagements are assessed in their aftermath.

Both strategy and tactics deal with using available military forces to accomplish objectivesâthat is, what it is that you want to achieve by the use of force. An overly simple but helpful way of describing the two terms is to think of strategy as pertaining to the

war

as a whole and tactics to the

battles

that are part of the war. Another simplification is that strategy can be thought of as

the plan

and tactics are the ways that plan

is executed.

Neither of these descriptions is completely accurate, however, and both fail to account for the variations and the overlaps sometimes encountered in the usage of these two words. For example, the planning for a major battle may be described as strategic, rather than tactical.

Much of the difference between the two depends upon size and scale. Strategy often involves larger components (such as fleets) and usually is

more long-term in duration (years, months, weeks). Tactics are smaller in scale (involving individual ships, for example) and shorter in duration (days, hours, minutes). Strategy can be employed in both war and peace, but tactics are generally linked to combat operations. Strategy is usually carried out by military commanders of high rank, while tactics can be employed by virtually anyone in contact with an enemy, from admirals to petty officers.

In the case of the Battle of the Coral Sea, the Pacific Fleet commander, Admiral Nimitz, made the decision to send his available carriers to Australian waters to prevent the Japanese from invading Port Moresby on the southeastern side of New Guinea, knowing that the Allies' loss of Port Moresby would give the Japanese a favorable geographic advantage and put Australia in serious jeopardy.

That was a

strategic

decision made by a high-ranking officer involving large forcesâtwo carriers and their escorts, a large percentage of all forces then available in the Pacific Theaterâover a relatively long period of time (in the vast reaches of the Pacific it can take weeks to reposition forces). Once Admiral Nimitz had planned his strategy, he then turned operational command over to his subordinate commanders to devise the tactics that would accomplish the objective of preventing the Japanese from taking Port Moresby.

During the actual battle on 8 May, the Japanese took advantage of the weather by hiding under the available clouds so that U.S. pilots would have difficulty spotting them, and

Zuikaku

was able to avoid damage by hiding in a passing rainsquall. Because the weather was clear around the U.S. carriers, the Japanese dive-bombers were able to dive on the carriers with the sun behind them, making it difficult for the American Sailors manning the antiaircraft guns to see them. These actions were

tactical

in nature, some made by captains (the commanding officers of the carriers) and some made by lieutenants (the dive-bomber pilots).

When Japanese torpedo bombers came skimming in at low altitude,

Lexington

's captain ordered a starboard turn to minimize the target profile of his ship. To thwart that maneuver, the Japanese pilots came in on both bows, so that if their target changed course in either direction, she would present a broadside aspect to their torpedoes, increasing the likelihood of a hit. These were decisions made in the heat of battle that were designed to give a tactical advantage.

Coupled with courage and skill, the tactics employed during the battle by the ship captains, pilots, gunners, and others had much to do with the survival or the loss of the individual units. When the smoke had cleared and the fleet commanders had withdrawn their forces, the score in a purely

tactical sense seemed to favor the Japanese. They had lost only a light aircraft carrier compared to the U.S. loss of a full-sized attack carrier, as well as a destroyer and an oiler.

But in the greater strategic sense, the Americans actually fared better than the Japanese. The elation evident in the flight commander's report, “Scratch one flattop!” when U.S. pilots were able to sink the light carrier

Shoho

was appropriate not only in the heat of the moment, but also because the loss of the air support that

Shoho

was tasked with supplying to the invading forces caused the Japanese commander to turn his task force around, abandoning the attack on the Port Moresby. Because taking Port Moresby was a major objective of the Japaneseâthe primary reason for the Battle of the Coral Seaâthe loss of

Shoho

was a victory of

strategic

importance for the Americans. Going back to the earlier simplistic definitions of strategy and tactics, the

battle

had gone in favor of the Japanese, but the effect on the

war

had favored the Americans. Viewed this way, the assessment that the battle had been a

tactical

victory for the Japanese navy and a

strategic

victory for the U.S. Navy is a reasonable assessment.

There was another strategic consideration as well. Because the carriers

Zuikaku

and

Shokaku

were temporarily put out of action at Coral Sea, they were not available for the next major battle at Midway. The number of carriers that faced off in that critical battle was three for the Americans and four for the Japanese, a much better matchup for the Americans than the three-to-six ratio it might have been. Because Midway proved to be a pivotal battle in the war, the Japanese suffered a defeat from which they never fully recovered. Thus, the relatively minor damage inflicted on

Zuikaku

and

Shokaku

had important strategic effects on the outcome of the war.

At the Battle of Valcour Island during the American Revolution, the Americans employed good tactics to offset some of the advantages enjoyed by the British as they carried out their strategy of trying to split the colonies along the Hudson River corridor in New York. Although the British had a far superior force, the Americans placed their forces in Valcour Bay so they would have the upwind advantage. This caused the British ships sailing southward along Lake Champlain to have to come about and attack into the windâno easy task for vessels powered by sails, especially those that were square-rigged. This was an excellent example of tactical positioning on the part of the Americans; it was enhanced by the crescent formation they used, which allowed them to concentrate their fire. They also cut spruce trees and rigged them along the sides of their vessels to make them blend in with the

surrounding tree-lined shores and to provide some protection against small arms fire when the British got in close.

Despite these tactical enhancements, the American force was ultimately no match for the superior British fleet and the victory went to the latter. But just as at Coral Sea, the tactical victory for one side proved to be a strategic victory for the other.