A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy (30 page)

Read A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy Online

Authors: Thomas J. Cutler

Hunley

's brave crew were not the only casualties. Other crews had paid the ultimate price while testing the strange new vessel; even her designer, H. L. Hunley, was lost on one of these test dives.

Essentially a converted boiler about forty feet long and four feet wide, she was powered by a hand crank that turned a screw propeller when manned by most of her crew. Ballast tanks at either end of the vessel provided buoyancy and permitted her to submerge. Weights attached to her underside could be detached from the inside if necessary. She could stay submerged for about half an hour before needing to come up to replenish air through breathing tubes. The crew used a burning candle to warn when oxygen was running out.

This primitive technology was just a little more sophisticated than that used in an earlier submarine built during the American Revolution a century earlier. Named the

Turtle,

she was a one-man submarine that looked like an upright egg and used a foot pedal to flood the bilges in order to submerge. A hand pump could eject the water to bring the sub back up. Like

Hunley,

she relied on a hand crank for propulsion and had detachable weights. Unlike the Confederate version,

Turtle

did not have a very effective means of weapon delivery. She carried a keg of powder that was to be

attached to the underside of an enemy vessel and subsequently detonated by a timing device.

Ezra Lee, a sergeant in Washington's Continental Army, volunteered to take

Turtle

out in New York harbor to attack the anchored British flagship. He successfully maneuvered the submarine into position but was unable to attach the powder keg before being discovered by the enemy. Pursued by an enemy boat, Lee cut the keg loose as he withdrew. It exploded spectacularly but harmlessly among the ships in the anchorage. Although

Turtle

was unable to attack the Royal Navy successfully, many of the British ships hoisted their anchors and moved farther downstream as a result of Lee's attempt.

From those early ventures beneath the sea came one of the most formidable weapons in the history of warfare. Before the nineteenth century had come to a close, John Holland had designed a workable submarine, and by 1900 the U.S. Navy had its first, appropriately named USS

Holland.

Before the beginning of World War I, the Navy had twenty-five subs in service. Because these early craft were so small, they were called “boats” rather than ships, and the term has stuck to this day, even though USS

Louisville,

the submarine who first fired a Tomahawk missile into Iraq, is 360 feet long and displaces more than seven thousand tons. Submarines nearly changed the outcome of World War I, and they played a vital role in the U.S. victory in the Pacific during World War II. Nuclear-powered submarines were likewise key components of the U.S. victory in the Cold War, though none ever fired a shot.

Today, submarines continue to be a principal component of America's nuclear deterrence strategy, while expanding their roles in tactical missile attack and support of Special Forces operations. They are manned by Sailors who routinely descend into regions once considered off-limits to mankind. Like the surface above, the undersea regions of the world are now the dominion of the U.S. Navy because of Sailors who dared to go into the unknown.

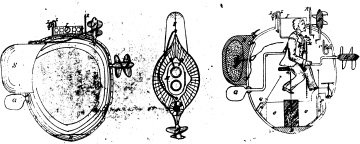

Design drawings of

Turtle,

the first operational submarine. She attacked a British ship in New York harbor during the American Revolution.

U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

In March 1898, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt wrote to Secretary of the Navy John D. Long about some experiments that were being conducted with a device he called an “aerodrome.” He informed Long that “the machine has worked,” and then advised, “It seems to me worthwhile for this government to try whether [or not] it will work on a large enough scale to be of use in the event of war.” The Navy and the Army formed a board to investigate the matter and concluded there was merit in Roosevelt's suggestion. The Navy Bureau of Construction and Repair, on the other hand, concluded that the “apparatus,” as they called it, “pertain[ed] strictly to the land service and not to the Navy.” How wrong they were!

Although these lighter-than-air aerodromes would never play a major role in naval warfare, other flying machines, pioneered by the likes of the Wright brothers, would prove that earlier board's decision to be a bit hasty. Later members of that same Navy board gave this new idea the chances it needed, once again changing naval warfare forever.

A little more than forty years after the initial Wright brothers' flight, the Battle of Midway would prove to be the decisive turning point in the largest war the world had ever seen, and the entire engagement was decided by fleets that never laid eyes on one anotherâexcept from the air. Instead of Roosevelt's “aerodromes,” the flying machines at Midway were dive-bombers, fighter aircraft, and torpedo bombers, and they were launched from ships far out at sea. Naval air had become the predominant weapon for war at sea in just a few decades.

Conservative impediments were overcome by larger events and by the vision and courage of some Sailors who sensed that a revolution was upon them and who decided their only choice was to join or get out of the way. One such Sailor was Captain Washington Irving Chambers. Noting in 1910 that the Germansâwho were rapidly becoming a world powerâwere planning to launch an airplane from a ship, he decided that the U.S. Navy should make the attempt first. Unable to get funding from the Navy Department, he persuaded a wealthy publisher to contribute one thousand dollars to the project. He then persuaded a pilot by the name of Eugene Ely to make the attempt. On 14 November, Ely took off from a specially constructed

platform that had been erected on the bow of cruiser

Birminghamâ

then anchored in Hampton Roads, Virginiaâand then landed near a row of beach houses on shore.

Two months later, on 18 January 1911, Ely again piloted an aircraft for the Navy, but this time he successfully

landed

on a platform that had been erected on the afterdeck of USS

Pennsylvania

in San Francisco Bay. An hour later, he took off again and landed safely ashore. Besides the primitive aircraft he was flying, Ely depended upon a series of lines attached to sandbags as the arresting gear to facilitate his landing on the ship, and he used a bicycle inner tube wrapped around his waist as a life preserver. Rudimentary as it might have been, this experiment proved the viability of aircraft carrier operations and marked the beginning of the most sweeping change to naval warfare that had ever occurred.

Innovative and courageous Sailors from seamen to admirals carried forth the work that Ely had started. Over a relatively short period of time, the primitive experiments on

Birmingham

and

Pennsylvania

were transformed into a powerful instrument of naval warfare, conducted with astounding efficiency and reliability despite the great dangers involved. Those who have ever witnessed flight operations on an American aircraft carrier are consistently awed by the precise choreography of so many people doing so many things with such powerful machines amidst so much noise and surrounded by so much potential death and destruction. From the aircraft handlers in their yellow shirts to the refueling teams in purple, from the red-shirted ordnance loaders to the pilots in g-suits, and so on, it is a ballet of sorts, in which the performers are artists in their prime, and every successful performance deserves a standing ovation.

Many Sailors paid with their lives for this boldness, but their sacrifices have given the Navy another powerful arm to project its power over the seas and into the littoral regions of the earth. Whether striking targets in the once-forbidden regions of mountainous Afghanistan or flying deterrent patrols in the airspace between Communist China and Taiwan, U.S. naval aircraft play a vital role in both war and diplomacy: putting muscle behind words and ideals and applying measured force, when necessary, to protect America's interests in virtually any corner of the world.

One Sailor's adventure into the unknown began rather ignominiously, yet ended in glory. He had served in the destroyer

Cogswell

during World War II and then entered flight school after the war, earning his wings in 1947. A gifted aviator, he attended Navy Test Pilot School, subsequently helping

the Navy develop an in-flight refueling system and conducting early trials on the first angled carrier deck. He later flew test flights in the F3H Demon, F8U Crusader, F4D Skyray, F11F Tigercat, and the F5D Skylancer. But all of these contributions would pale in light of his historic flight on 5 May 1961.

Strapped into his aircraft waiting for launch after several delays, he suddenly realized that he had a problem. Speaking into his radio headset, he reported, “Man, I've got to pee!”

“You what?” came the response.

“You heard me. I've got to pee.”

Alan Shepard was sitting atop a Redstone rocket, strapped into a space capsule named

Freedom 7,

waiting to make history by being the first American to go into outer space, when he realized that despite all the scientific innovations and technological wonders that had gone into preparing for this moment, no one had thought of this need.

Shepard was told that no time had been factored in to the launch sequence to allow him to leave the space capsule. By this time, he was getting truly desperate, and he said he was going to have to let go. The aeronautical engineers were afraid that if he did so, the liquid inside his flight suit might short-circuit some of the many electrical leads that were attached. The mission seemed in serious jeopardy.

It was Shepard himself who came up with a low-tech solution. He said over the radio to fellow astronaut Gordo Cooper in mission control, “Tell 'em to turn the power off!” It seemed like a possible solution that would allow him to urinate without shorting out any of the leads, so Cooper checked with the engineers. With a less than convincing shrug, they gave their assent. Laughing at the absurdity of the situation, Cooper told the man who was about to make history: “Okay, Alan. Power's off. Go to it.”

Lying on his back in the capsule, with his face to the heavens, about to challenge the forces and laws of nature by literally reaching for the stars, Alan Shepard gave in to a basic law of nature that neither he nor any of the brilliant minds that had designed the mission could defy. Soon a pool of liquid formed at his back, soaked up by the heavy undergarment he was wearing. Power was restored, and the flow of oxygen in his suit began drying the unwanted puddle.

Then, at Shepard's urgingâ“Let's light this candle!”âthe huge rocket was ignited. Like Peter Williams and his shipmates who changed the way their Navy did business, and Ezra Lee and the other submarine pioneers who took their Navy into the depths of the sea, and Eugene Ely and countless other aviators who braved great dangers to lift their Navy into the skies, Alan Shepard took his Navy into the “final frontier,” the vast reaches

of outer space. Climbing to an altitude of 116 miles, and flying at speeds greater than 5,000 miles per hour,

Freedom 7

left the bonds of Mother Earth and entered the weightless world of outer space. Flying down the Atlantic Missile Range for 302 miles, the space capsule reentered the atmosphere and landed in the ocean to be recovered by the carrier USS

Champlain.

It was an astounding accomplishment that would lead the way to a landing on the Moon just eight years later. The first human to walk on the surface of the Moon was Neil Armstrong, a former Sailor. Shepard would also eventually land on the Moon, as would a number of other Sailors. Today, the Navy's presence in space is less human but no less vital to the missions of the operating forces. Satellites provide vital support in communications, navigation, weather forecasting, and intelligence. Many modern naval weapon systems rely upon technology developed as part of the space program, and some receive actual targeting data from space systems.