A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy (29 page)

Read A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy Online

Authors: Thomas J. Cutler

At about half past seven, excited voices reported that

Virginia

was under way and heading straight for helpless

Minnesota,

the latter still hard aground.

Monitor

's crew raced to their stations, closing hatches behind them, removing the stack, and placing protective covers over her running lights. Within minutes, she was steaming toward her Confederate counterpart.

To those watching from shore, it was evident that

Virginia

was much larger and more heavily armed than

Monitor,

and many anticipated seeing a quick end to this Union newcomer. On board

Virginia,

her chief engineer was astonished to see “a black object that looked like . . . a barrelhead afloat with a cheese box on top of it” come out from behind

Minnesota

and head right for them.

Peter Williams was at the helm as

Monitor

positioned herself between

Minnesota

and

Virginia.

Also crammed into the tiny space were the captain and Samuel Howard, who was acting master of the bark

Amanda.

The latter, being familiar with the waters of Hampton Roads and a brave man, had volunteered to serve as pilot for the Union ironclad.

Paymaster William Keeler had no assigned battle station, so he positioned himself in the turret in case he could be of assistance there. He watched in awe as the men loaded 175-pound projectiles into the big guns. Once they were loaded, Keeler noted that “the most profound silence reigned.” Sealed inside the armored turret, unable to see out with the gun ports closed, the men seemed almost to freeze in place as they waited for the battle to begin. Keeler thought, “If there had been a coward heart there, its throb would have been audible, so intense was the stillness.” Although he admitted no fear, Keeler did ponder their circumstance as he waited, noting that “ours was an untried experiment and the enemy's first fire might make it a coffin for us all.”

At last the awful silence was broken. Keeler could hear the “infernal howl” of

Virginia

's shells as they passed over

Monitor

on their way to

Minnesota.

The speaking tube between the turret and the pilothouse was not working, so the ship's executive officer, Lieutenant Samuel Greene, told Keeler to “ask the Captain if I shall fire.” Relaying through Daniel Toffey, the ship's clerk, the question was passed, and Captain Worden's reply was, “Tell Mr. Greene

not

to fire till I give the word.” He also told his executive officer “to be cool and deliberate, to take sure aim and not waste a shot.”

Worden calmly passed his conning orders to Williams, who expertly spun the helm in response. He maneuvered

Monitor

toward

Virginia,

closing the range, “approaching her on her starboard bow, on a course nearly at right angles with her line of keel, saving my fire until near enough that every shot might take effect.” When

Monitor

was sufficiently close, Worden stopped the engine and gave the order to commence firing.

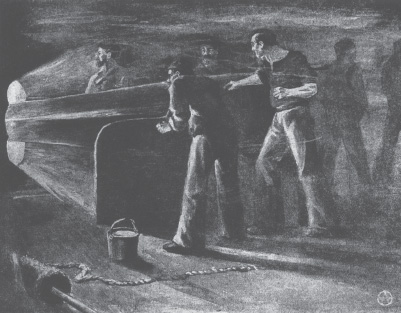

Inside USS

Monitor

's gun turret. Paymaster William Keeler noted that before the battle began: “The most profound silence reigned. If there had been a coward heart there, its throb would have been audible.”

Naval Historical Center

The executive officer “triced up the port, ran out the gun, and, taking deliberate aim, pulled the lockstring.” At that moment, naval warfare was indeed changed forever.

The two ironclads went at each other with a determined fury.

Monitor

's first shot struck her adversary at the waterline, and

Virginia

responded with a broadside that would have destroyed a wooden ship of the same size. To the great relief of Greene and the other Sailors inside the revolving cheese box, “the turret and other parts of the ship were heavily struck, but the shots did not penetrate; the tower was intact, and it continued to revolve.”

The two ships spiraled about one another, trading shots for quite some time, with neither able to strike a fatal blow. Their suits of armor withstood the terrible punishment each was attempting to inflict upon the other. One witness on the nearby shore later remembered, “Gun after gun was fired by the

Monitor

which was returned with whole broadsides by the rebels with no more effect, apparently, than so many pebblestones thrown by a child.” Inside the ironclads, the shots striking the metal did not

sound

like pebblestones; the din inside both vessels was almost unbearable as striking shot reverberated throughout their echo-chamber hulls.

Ironclads USS

Monitor

and CSS

Virginia

dueling in Hampton Roads. Inside the ships, the din was almost unbearable as shot bounced off their armored sides.

U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

The spirals grew ever tighter until the two ships were next to each other, firing at point-blank range. And still the shots glanced off

Monitor

's whirling turret and off

Virginia

's sloping sides, causing no more than dents and the awful clatter. It was clear that each had met her match, yet neither was able to prevail.

As the battle wore on indecisively, Williams continued working

Monitor

's helm in response to Worden's calm orders. At one point as they maneuvered around

Virginia

's stern, Williams could see the enemy ship by looking over Worden's shoulder through the forward window slit. He realized he was looking right into the muzzle of the Confederate's stern gun just twenty yards away. Worden was saying to Williams, “Keep her with a very little port helm, a very little,” when, suddenly, there was a great flash and a thunderous crash as an enemy shell slammed into the pilothouse. Williams was thrown from the helm and found himself on his hands and knees. The top of the pilothouse was partially torn off, and the light that poured in from above momentarily blinded Williams. Miraculously, the young helmsman was not seriously injured. His captain, however, was less fortunate. Worden had taken much of the blast full in the face, and his eyes were filled with smoke and burning powder. He staggered back, his hands to his face, and cried: “My eyes. I am blind!” With blood pouring down his face, Worden was taken to his cabin.

Trembling violently, his ears ringing from the concussion, Williams climbed to his feet and grasped the spokes of

Monitor

's helm. To his relief, the ship responded when he moved the wheel. Locating

Virginia

through one of the slits, he steadied his ship and began maneuvering her into position as he had seen Worden doing. For a time, until the executive officer could get to the pilothouse and take command, Williams was in sole command of the ironclad's movements.

By this time, the two iron contestants had fought for several hours, with neither ship suffering disabling damage. No one had been killed on either ship; only Worden was seriously injured.

Virginia

had fought a battle with enemy ships the day before;

Monitor

had fought a battle with the forces of nature that day as well. The result was that the men in both ships were exhausted. The two vessels had expended great amounts of coal and ammunition. It was time for this undecided but historic battle to end.

Virginia

headed for Sewell's Point and

Monitor

returned to her anchorage.

Both sides would claim victory in this first clash of the ironclads. In truth, it was, by most objective assessments, a draw. Northerners could rightfully

claim that

Monitor

had prevented

Virginia

from succeeding in her mission to destroy

Minnesota

and the other Union ships in Hampton Roads, and there certainly was a measure of victory in that. George Geer wrote a short letter to his wife after the battle that reveals maddeningly little about the battle itselfâtelling her she can read about it in the newspapersâbut he makes it clear how the Union leadership felt about the outcome: “Our ship is crowded with Generals and Officers of all grades both army and Navy. They are wild with joy and say if any of us come to the Fort we can have all we want free, as we have saved 100s of lives and millions of property to [

sic

] the Government.”

Circumstances would prevent these two ships from having a rematch.

Virginia

would survive just another two months. On 11 May, with Norfolk about to fall to Union forces, Confederate Sailors destroyed her to keep her from falling into enemy hands.

Monitor

lasted until the end of that same year, when she was lost in a storm off Cape Hatteras on New Year's Eve as she headed south to participate in blockade operations. Fourteen men were lost as she succumbed to twenty-foot waves and high winds.

George Geer and Peter Williams were still part of

Monitor

's crew when she went to the bottom of the Atlantic, but they were not among those lost. Geer left the Navy several years later, eventually using his skills as an engineer to make a good living in civilian life. Quartermaster Williams remained in the Navy and was eventually promoted to acting master's mate. For his courageous performance as

Monitor

's helmsman, he was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Lieutenant John Worden recovered from his wounds and commanded another ironclad in action the following year. When President Lincoln heard that Worden was recuperating in a friend's home in Washington, the president hurried to the house. Worden, his eyes still bandaged, heard Lincoln's voice, and said, “Mr. President, you do me great honor by this visit.” Lincoln paused a moment, then said, “Sir,

I

am the one who is honored.”

Although those two ships would never fight one another again, on that day in April 1862 the age of the ironclad had dawned. Many more ships would fight in the Civil War with steam-powered engines, forced-air ventilation, revolving turrets, and other new inventions. These vessels would soon take control of the seas away from the beautiful wooden sailing ships with their webs of lines and clusters of billowing canvas. By the time America would fight her next major warâthe Spanish-American War just thirty-six years laterâthe two major engagements of that clash would be fought by cruisers and battleships made of steel slugging it out with breech-loading, rifled guns in rotating turrets. The day

Monitor

fought

Virginia

(ex-

Merrimack

) marked the beginning of a revolution and the end of an era.

The duel of the ironclads was not all that was new to naval warfare during the American Civil War. Two years after the historic battle in Hampton Roads, on the night of 17 February 1864, USS

Housatonic,

a steam-powered sloop, was positioned about five miles southeast of Fort Sumter at Charleston, South Carolina, as part of the Federal blockade of the Confederacy. It was a clear night, bathed in bright moonlight, and the seas were calm. Thus, it was no surprise when one of

Housatonic

's lookouts spotted something in the water that “looked like a log.” Flotsam in these waters was not unusual, but an object moving toward his ship faster than the prevailing current was something worth the lookout's attention. After sounding the alarm, the lookout and several other Sailors opened fire with small arms, but to no effect. The “log” made contact with the ship's starboard side and a large explosion ripped off

Houstonic

's starboard quarter. Although just five Union Sailors were killed, the ship was fatally wounded, and she quickly went to the bottom.

The “log” had been CSS

Hunley.

With her 90-pound spar torpedo, she had earned the distinction of being the first submarine to sink an enemy vessel. It would prove to be a costly victory for the history makers, however; for reasons not entirely clear,

Hunley

disappeared on her way back from the attack, taking her entire crew of nine to their deaths.