A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy (40 page)

Read A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy Online

Authors: Thomas J. Cutler

The fleet made its way across the Atlantic and then southward along the coast of South America until they eventually found the straits that led to the

Pacific Ocean and today bear his name. The passage through these treacherous Straits of Magellan took thirty-eight days, during which the crews saw many fires from Indian camps burning on the nearby shores and so named the land

Tierra del Fuego

(“Land of Fire”).

Emerging from the straits, Magellan thought the Spice Islands were just a few days' sail away. He soon learned what every Sailor who has crossed the Pacific knowsâit is one big ocean! Four months later, suffering from starvation, thirst, and disease, the explorers reached the Philippines. Unfortunately for Magellan, his voyage ended there; on 27 April 1521, he was killed by the natives in the midst of a tribal war.

Sebastian del Cano took command of what was left of the expedition; he eventually made it back to Spain with one ship (

Victoria

) and eighteen crew members. It was a momentous achievement, but accomplished at great cost.

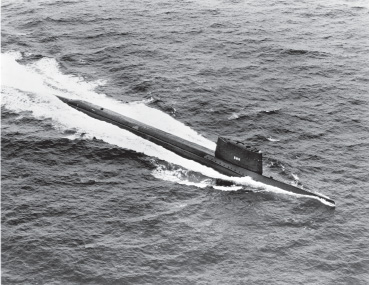

More than four hundred years later, the feat was repeated, but this time under different circumstances. In February 1960, USS

Triton

put to sea for her shakedown cruise. She was the fifth U.S. Navy ship to bear the name of the Greek demigod of the sea who was the son of Poseidon and who used his conch-shell trumpet alternately to summon storms and to still the sea. It was an appropriate name for a ship who, like her namesake, had harnessed the forces of nature: powering this modern warship was a nuclear reactor that gave her great speed and virtually unlimited sea-keeping ability.

USS

Triton,

one of the Navy's earliest nuclear submarines, was destined to make history on her shakedown cruise.

U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

To prove her capabilities,

Triton

sailed completely around the world, following the same track that Magellan had used. What was markedly different this time, however, was that she made the voyage nonstop in sixty days and twenty-one hours, and she made it

under the water

!

Triton

was one of the first generation of nuclear-powered submarines. Her epic circumnavigation proved the great capabilities of this new kind of ship and greatly enhanced the nation's prestige at a time when image was one of the weapons of the Cold War with the Soviet Union. Her crew received the Presidential Unit Citation and her skipper, Captain Edward L. Beach, was awarded the Legion of Merit. Today,

Triton

's dive stick resides in the lobby of the Naval Academy's Beach Hall, headquarters of the U.S. Naval Institute.

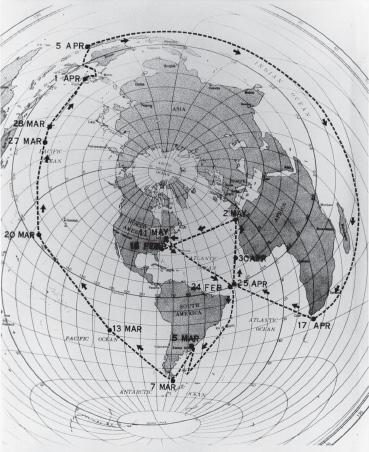

Triton

's track as she made her historic underwater circumnavigation.

U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

As a young girl, Grace Brewster Murray had an unusually inquisitive mind. When she was seven years old and wondered how her alarm clock worked, she disassembled it. When she was unable to get it back together, she got another and took it apart to see if she could figure it out. When that failed, she got another, and another. By the time she finished her quest, all seven of the household alarm clocks lay in pieces.

But Grace Murray Hopper (she married Vincent Foster Hopper in 1930) put her inquisitiveness to good use. She earned a bachelor's degree in mathematics and physics from Vassar College and went on to earn both a master's degree and a PhD in mathematics from Yale University (she was the first woman to earn the latter). When she joined the Navy in 1943 in the midst of World War II, a wise detailer decided she might be a good person to assign to the Bureau of Ordnance in a special program known as the Computation Project. In those days, computers were just beginning to make their debut, and this made Hopper one of the pioneers.

The Computation Project was a joint effort of the Navy, the IBM Corporation, and Harvard University. Grace Hopper became one of the programmers of the world's first large-scale computer, the Mark I. This early machine was no desktop personal computer. Describing it as “an impressive beast,” Hopper remembered it as “51 feet long, 8 feet high, and 5 feet deep.” She mastered the Mark I and its improved versions, the Mark II and Mark III.

One day while diagnosing a problem in one of these temperamental machines, she found that the cause was a moth trapped in one of the relays. Extracting it with a pair of tweezers, she then taped the expired moth into the computer's logbook, with an explanation that the problem had been a “bug” and told her supervisor that the computer had been “debugged.” To this day, Grace Hopper is credited with coining the term that has endured as part of the computer lexicon.

After the war, she remained in the Naval Reserve while continuing her career in computing. Graduating from the highly mechanized Mark series computers, she began work on a newcomer called UNIVAC (Universal Automatic Computer). With its arrays of vacuum tubes and magnetic drums, this was the first computer that could rightfully be called “electronic.”

In the years that followed, Hopper's reputation grew as she worked to make computers better and better. Among her many achievements was her contribution to creating the first language that allowed programmers to speak to computers with words rather than numbers.

In 1966 Grace Hopper retired from the Naval Reserve, but the Navy soon realized the importance of computers and recalled her to active duty for six months. That half-year turned into nearly two decades of additional service!

While serving in the Naval Automation Data Command, she also traveled the world, speaking to thousands about the future of computers. Sometimes these speaking engagements earned her honoraria, which she turned over to Navy Relief (more than thirty-four thousand dollars). One of her constant themes was that change could be good. She was often frustrated when she would hear yet another Sailor say, “But that's how we've always done it.” With a wry smile on her wizened face she was heard to reply, “Someday I'm going to shoot somebody for saying that.” To prove her point that convention is not always necessary, she kept a clock on her wall that kept perfect time but ran counterclockwise. She also always carried a one-foot piece of wire with herâbecause one foot is the distance light travels in a nanosecond. She would brandish it before listeners and explain why programmers should not waste time, not even a nanosecond.

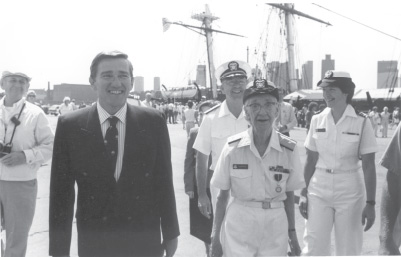

Grace Hopper at her

second

retirement ceremony with Secretary of the Navy John Lehman.

U.S. Navy

Grace Hopper, then a rear admiral, eventually retired from the Navy a second timeâthis time for goodâin 1986. She had earned an array of awards, both military and civilian, too numerous to list. Her retirement ceremony was held onboard USS

Constitution

; thus the oldest active duty naval officer in service ended her long career on the decks of the Navy's oldest commissioned warship.

Grace Murray Hopper died on New Year's Day 1992. Just five years later, an

Arleigh Burke

âclass guided missile destroyer was commissioned bearing her name. Officially USS

Hopper,

the ship is better known throughout the fleet by the nickname Rear Admiral Hopper had earned during her long and extraordinary career: “Amazing Grace.”

On 10 June 1965, a reinforced Vietcong regiment attacked the compound of Detachment A-432, 5th Special Forces Group, at Dong Xoai, fifty-five miles northeast of Saigon in South Vietnam. Facing the enemy onslaught along with the eleven Army Green Berets were nine Sailors.

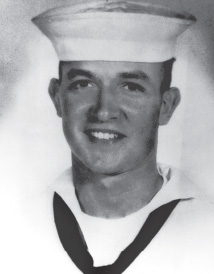

One of the Sailors was Construction Mechanic Third Class Marvin Shields. The young petty officer had joined the Navy primarily to build things, but on this particular day, he and his shipmates were going to have to fight alongside the Army commandos.

Early in the battle Shields was wounded, but he continued to supply his fellow Americans with needed ammunition for the next three hours. When the enemy forces launched a massive attack at close range with flamethrowers, hand grenades, and small-arms fire, Shields stood his ground alongside his shipmates and the Soldiers. Wounded a second time in this assault, Shields nevertheless ignored the mortal danger and helped a more critically injured Soldier to safety while under intense enemy fire.

For four more hours, Shields and the others maintained a barrage of fire that kept the enemy at bay. When the compound commander, Second Lieutenant Charles Q. Williams, asked for a volunteer to help him take out an enemy machine-gun emplacement that was endangering the lives of all the Army and Navy personnel in the compound, Shields volunteered. Armed with a 3.5-inch rocket launcher, Shields and the Green Beret commander advanced on the enemy emplacement despite heavy fire from several enemy positions. The two men succeeded in taking out the enemy machine-gun nest and then attempted to return to the relative safety of the compound. The young Sailor's luck had at last run out. Struck a third time, this wound would prove fatal.

Construction Mechanic Third Class Marvin Shields had joined the Navy to build things, but in Vietnam he stood alongside Army Green Berets in a vicious firefight.

Naval Historical Center

For his courageous actions, Marvin Shields was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, the first Sailor to win the nation's highest honor for action in Vietnam.

In April 1971, to further honor this intrepid Sailor who fought so ferociously alongside some of the Army's fiercest Soldiers, the fifteenth

Knox

-class destroyer escort was commissioned into the Navy as USS

Marvin Shields.

This seemingly strange situation, with Sailors fighting ashore like soldiers, was actually not so unusual. Marvin Shields and the other Sailors were part of a special Navy unit: SeaBee Team 1104. They were there in the jungles of Southeast Asia to build a base, just as they had in many other parts of the world during earlier wars.