A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy (4 page)

Read A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy Online

Authors: Thomas J. Cutler

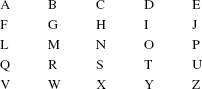

Although forbidden to communicate with one another, the Americans used a quadratic alphabet code that was simple to learn and could be used by tapping on the walls of their cells or even as a series of coughs. With practice, many became very proficient at using it. The letters of the alphabet were arranged in a five-by-five grid (excluding

K

as unnecessary, to keep it symmetrical).

The first series of taps represented the number in a row (across) and the second indicated the number in the column (down). So five taps followed by four taps would be the letter

U

; three taps then four would be

S

; three taps followed by three would be

N

; and so on. With patienceâand courageâa great deal could be transmitted this way.

Another means of fighting off despair was for the POWs to maintain their sense of honor. Their tormentors could take away the Americans' sense of dignity by providing just a tin can for a toilet. They could challenge their sanity by allowing them nothing to read except Communist propaganda. They could sap their strength by keeping them confined in leg

irons that prevented them from exercising. They could torture them in ways that made death a tempting alternative. But as long as these men could maintain their sense of personal honor, the enemy could not defeat them.

They accomplished this in a number of ways, not the least of which was their commitment not to accept an early release. At times, to serve their propaganda purposes, the North Vietnamese would offer to let one or more of the POWs go home to America. Accepting the opportunity to leave this hell, to be reunited with their families, was incredibly tempting. But through their tap code and other means of communicating, they vowed to each other that not one would go home until

all

could go home.

Doug Hegdahl was no exception. As any sane person would, he desperately wanted to go home, yet his sense of personal honor made that an impossibility. At a very young age, fate had placed him in the most challenging circumstance of his entire life. His fellow prisoners were older; they had college educations and a great deal more training, and they were being paid more than he was. But in spite of his youth, inexperience, and bizarre circumstances, Hegdahl's upbringing in South Dakota and the training he had received in the Navy made him wise enough to realize that while accepting an early release might be a welcome solution to his misery in the short term, it would mean a lifetime of regret. He had seen a few of the POWs accept early releases, and it was clear to him that they were wrong to do so. It was clear they had traded their honor for their freedom. Hegdahl resolved that if he were going to survive this ordeal, he wanted to live the rest of his life knowing he had behaved with honor.

But even this simple (if incredibly difficult) commitment was going to be challenged. As it happened, Dick Stratton and others had a different plan for Seaman Apprentice Hegdahl.

During one siesta period, Hegdahl asked Stratton if he knew the Gettysburg Address. Using a brick as a writing implement, the two men began to scrawl it out on the floor of the cell until they were convinced they had it right. Then Hegdahl, staring thoughtfully at their creation, asked, “Can you say it backward?” Not surprisingly, Stratton said, “No.” Hegdahl began to do just that. Stratton followed along using their floor-inscribed version and, to his utter astonishment, found that Hegdahl was doing it without error. Stratton concluded that this was no ordinary memory. He was further convinced when Hegdahl revealed to him that an Air Force officer named Joe Crecca had taught him how to memorize the names, ranks, and services of all the pilots imprisoned in Vietnam, at that point more than 250. It was also clear that Hegdahl had memorized a great deal of information about his captors, the prisons he had been in, and what he had managed to see beyond the prison walls when his guards were napping.

Soon, tap-coded messages were flying about, and the senior POWs concluded that Seaman Hegdahl could do all of the POWs much good and their enemies more harm if he accepted an early release and carried his information home to the United States. The North Vietnamese had deliberately withheld the identities of the men they had in captivity as one part of their many attempts at undermining the will of the American people. Consequently, many Americans had no idea whether their loved ones were alive or dead. Finding out that your husband or son was a POW in North Vietnam was no pleasant revelation, but it was far better than living in uncertaintyâand infinitely better than finding out he was dead.

And there was another factor. In those early days of the Vietnam War, the brutal treatment of the American POWs was not widely known or recognized. The North Vietnamese had convinced many sympathizers in the world that they were treating their captives humanely. Doug Hegdahl, of course, knew better.

If he could take his head full of information back to the United States, he could give renewed hope to many of those waiting in dreadful uncertainty, he could help to dispel the fiction of humane treatment, and he could also provide other knowledge to military authorities that might well prove useful. To the senior POWs, it was clear that Hegdahl should accept an early release.

But it was not so clear to the young seaman apprentice. Hegdahl had seen the way the other POWs had felt about those among them who had accepted an early release, and he shared their disappointment in those men. He had heard Stratton declare, “I'd have to be dragged feet first all the way from Hanoi to Hawaii screaming bloody murder all the way.” From early in his captivity, Hegdahl, like the vast majority of his fellow POWs, had staked his personal honor on staying until the day they

all

would be released, no matter how long that might take. Some of the POWs had been there two years longer than he had. It just did not seem right for him to go.

Stratton worked on Hegdahl, trying to convince him that he was an exception, that he could go home and take his honor with him. Stratton told him: “You are the most junior. You have the names. You know firsthand the torture stories behind many of the propaganda pictures and news releases. You know the locations of many of the prisons.”

In the end, it took a direct order before Hegdahl relented and accepted an early release, taking his head full of names and other accumulated intelligence back to the United States. Before going, he told Stratton he was worried that once he “spilled the beans” back in the safety of America, the Communists would take revenge on Stratton and the others. Stratton looked Hegdahl in the eye and said: “Don't worry about me. Blow the whistle on the bastards.”

There was no question that the POWs had made the right decision in making an exception of Seaman Apprentice Hegdahl. The Communists soon learned that they had gravely misjudged “the incredibly stupid one.” As predicted by Stratton and the others, Hegdahl's ability to recite the names of the other POWs proved invaluable, even if the people debriefing him were somewhat surprised to find that he

sang

the names to the tune of “Old MacDonald Had a Farm” (his unorthodox but effective way of remembering the information).

The other information he brought back proved useful as well. He was able to pinpoint the exact location of the prison the POWs had dubbed “The Plantation,” describing it as “located at the intersection of Le Van Binh and Le Van Linh, number 17,” something he had learned one day while sweeping around the camp's front gate. He told all who would listen of the terrible conditions and torture. He eventually went to Paris, where North Vietnamese and American negotiators were meeting. When one of the North Vietnamese delegates said, “Our policy is very humane in the camps,” Hegdahl responded, “I was there.” That ended any further reference to “humane” treatment of the POWs.

One day back in Hanoi, Dick Stratton found himself facing another interrogation, but this one was to prove different from the many others he had endured over the years. His captors brought him into a room where a table had been laid with cookies, candy, sugared tea, and quality cigarettes. This was not unusual; the Communists would often tempt the POWs with such things or use them as a means of torment by letting the prisoners see such nice things but not allowing them to consume them. A North Vietnamese interrogator, dressed in a tailored suit and wing-tipped shoes instead of the drab military garb his interrogators normally wore, entered the room. It appeared that he might be some sort of government officialâdefinitely higher up the North Vietnamese pecking order than the usual tormentors. With a very serious look on his face, the Communist asked, “Do you know Douglas Hegdahl?”

Stratton thought, “Uh-oh, here it comes.” He answered, “You know I do.”

Without changing expression, the interrogator said, “Hegdahl says that you were tortured.”

Stratton laconically replied, “This is true.”

“You lie,” the Vietnamese said, his voice rising.

Stratton calmly rolled up the sleeves of his pajama-like striped prison uniform and pointed to the scars on his wrists and elbows. “Ask your people how these marks got on my body; they certainly are not birth defects!”

The interrogator examined the marks carefully and then sat back, staring at Stratton. At last he said a strange thing. “You are indeed the most

unfortunate of the unfortunate.” Stranger still, he then got up and left the room, leaving Stratton with the table full of food and cigarettes. It was not until some time later that Stratton was able to figure out what had happened. This encounter had occurred shortly after Doug Hegdahl had openly accused the Communists in Paris of having killed Stratton. “The incredibly stupid one” had figured that by doing so, the Communists would likely want to keep Stratton alive so that they could produce him at the end of the war to prove Hegdahl wrong.

Beak Stratton did survive. He eventually came homeâalong with the other POWs who had preserved their personal honor by remaining in captivity, some for more than eight years. Stratton remained in the Navy and retired as a captain after many years of service. Today, he maintains a Web site where he has posted the following words: “âThe Incredibly Stupid One,' my personal hero, is the archetype of the innovative, resourceful, and courageous American Sailor. These Sailors are the products of the neighborhoods, churches, schools, and families working together to produce individuals blessed with a sense of humor and the gift of freedom, who can overcome any kind of odds. These Sailors are tremendously loyal and devoted to their units and their leaders in their own private and personal ways. As long as we have The Dougs of this world, our country will retain its freedoms.”

Douglas Hegdahl went on to serve the Navy for many years as an inspirational and highly effective instructor at the James B. Stockdale Survival, Evasion, Resistance, and Escape School in Coronado, California, where he was able to prepare thousands of others for the challenges they might someday face if they fell into enemy hands. He never lost his wry sense of humor. One day, some thirty years after his imprisonment in Hanoi, Hegdahl confessed that he'd fooled Beakâhe had

not

been able to recite the Gettysburg Address backward. He had been reading it over Stratton's shoulder as his gullible senior had his head down following along. That feat of memory may have been a ruse, but the one that counted was not.

The POWs have occasional reunions, where they gather to reinvigorate the bonds of friendship and mutual respect that were forged during their terrible ordeal. They do not invite those who took early releases without the consent of the others, but they

do always

invite Doug Hegdahl.

At a reunion in Yorba Linda, California, in 1998, Douglas Hegdahl paid a special tribute to his fellow POWs by singing a song. It was to the tune of “Old MacDonald Had a Farm,” and the lyrics were, in alphabetical order, the names, ranks, and services of more than 250 American POWs who, like him, had come home with honor.