A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy (7 page)

Read A Sailor's History of the U.S. Navy Online

Authors: Thomas J. Cutler

A gun crew at work.

Naval Historical Center

For more than an hour, Harvey and the others of Lieutenant Sterett's division repeated the process. As they labored, the confused sea frequently doused them with wind-driven spray, causing clouds of steam to rise from the cannon's heated barrel. The noise was deafening, the odors of burning powder and running perspiration filled the air, and musket balls and deadly wooden splintersâsome of them several feet longâflew about, threatening to tear off a limb or snuff out a young life in an instant. As Harvey and his mates rolled their gun forward to fill the opening, the young Sailor caught occasional glimpses of the enemy ship and saw the terrifying sight of her cannons winking bright flashes at them.

And then it was over. With the French ship's rigging a shambles, her crew decimated and in disorder, her rails shattered, and her hull pierced in many places,

l'Insurgente

's captain struck his flag in surrender.

Loud our cannons thundered, with peals tremendous roar,

And death upon our bullets' wings that drenched their decks in gore.

The blood did from their scuppers run,

Their chief exclaimed, “We are undone,”

Their flag they struck, the battle was won,

By brave Yankee boys.

When the French captain was brought on board

Constellation

in the aftermath, Captain Truxtun asked him, “Your name, sir, and that of your ship.”

“I am Capitaine de Fregate-Citizen Michel-Pierre Barreaut, commanding the French national frigate

l'Insurgente

of forty guns,” came the reply.

Truxtun then said, “You, sir, are my prisoner,” and, in the custom of the day, relieved the Frenchman of his sword.

Barreaut later told Truxtun that “your taking me with a ship of the French nation is a declaration of war.” Truxtun responded by reminding the Frenchman of early transgressions by the French that had led the United States to take such action. “If a capture of a national vessel is a declaration of war,” Truxtun said, “your taking the

Retaliation

commanded by Lieutenant Bainbridge, which belonged to the United States and regularly placed in our Navy, was certainly a declaration of war on the part of France against the United States.” Barreaut did not respond.

French casualties were high. Lieutenant John Rodgers was the first to board the defeated ship, and in a letter home he described what he saw: “Although I would not have you think me bloody minded, yet I must confess the most gratifying sight my eyes ever beheld was seventy French

pirates (you know I have just cause to call them such) wallowing in their gore, twenty-nine of whom were killed and forty-one wounded.”

In contrast, just one American died in the battle, but it was a tragic loss. Ironically, while defending the honor of his nation, poor Neal Harvey failed to uphold his own. In the heat of battle, he ran from his post. Upon noticing his absence, Lieutenant Sterett ran him down and then ran him through with his sword. The incident later caused a great deal of debate, and Sterett inspired his supporters and appalled his detractors when he wrote to his brother, “You must not think this strange, for we would put a man to death for even looking pale in

this

ship.”

Such passionâhowever extremeâwas no doubt a contributing factor to the one-sided outcome of the battle. “

This

ship,” as Sterett had referred to

Constellation,

had won an amazing victory. A fledgling navy had stood up to a considerably more powerful one and prevailed. It was a risky venture for the Americans, considering the world situation and the possible reactions of a much more powerful French nation, which by that time was well on its way to conquering most of continental Europe. But it had been dictated as a matter of national honor. To do otherwise would have jeopardized the new nation's position in the world. Sometimes respect is earned through diplomacy and restraint, but other times it must be demanded by force of arms.

President Adams told his cabinet that

Constellation

's victory would ensure that American ministers would not again be treated so dishonorably when they came to negotiate. The secretary of war added, “The only negotiation compatible with our honor or safety is that begun by Truxtun in the capture of

L'Insurgente.

”

Even in London, where respect for the tiny U.S. Navy was not abundant, the merchants and underwriters of Lloyd's, the world's foremost maritime insurance company, sent Truxtun a beautiful silver urn in recognition of

Constellation

's achievement.

When word spread throughout the United States, there was a great out-pouring of appreciation and congratulations. All over the country, parades, cheering crowds, special dinners, and gun salutes honored

Constellation

's victory. Toasts were heard everywhere, calling the ship the “vanguard of America's naval glory” and, referring to the infuriating XYZ Affair, naming Truxtun “our popular envoy to the French, who was accredited at the first interview.”

And there were songs. In Baltimore there was “Huzza for the Constellation”; in Philadelphia, “Constellation: A Wreath for American Tars”; and in Boston, “Truxtun's Victory.” And in taverns up and down the coast, there was “Brave Yankee Boys.”

Now here's a health to Truxtun who did not fear the sight

And all those Yankee sailors who for their country fight,

John Adams in full bumpers toast,

George Washington, Columbia's boast,

And now to the girls that we love the most,

My brave Yankee boys.

So, in the end, Sailors of all ranks in the U.S. Navy must defend two kinds of honor. First, there is the nation's honor, which must be upheld through various means if this great nation is to remain free and effective on the world stage. Second, there is the personal honor of each individual Sailor, which must be maintained if Sailors are going to remain true to themselves and their shipmatesâand to continue to like what they see in the mirror for the rest of their lives.

| Courage | 2 |

There are many kinds and degrees of courage. It takes courage for a young man or woman to enlist in the armed forces of their nation; for a Sailor to climb down a Jacob's ladder to a boat that is pitching violently in a stormy sea; for a petty officer to tell his chief that he made a mistake; for a coxswain to make her first landing; for a corpsman to stop a Marine's arterial bleeding while enemy rounds are cracking all about; for a fireman to take the test for third class petty officer; for a gunner's mate to man a weapon as a replacement for her shipmate who was just killed a moment before; for a brand-new ensign to lead for the first time; for an airman to report a case of sexual harassment; for an electronics technician to climb the mast to fix a wiring problem in the TACAN antenna; for a nozzle man to lead a hose team into a compartment full of flames and smoke; for an officer to put his career on the line over a matter of conscience; for a master chief to put in his papers for retirement after thirty years of service. These are all acts of courage that occur every day in the United States Navy.

The rewards for these acts of courage vary. On rare occasions they result in the awarding of a medal such as the Bronze Star or Navy Cross. Sometimes they result in the achievement of a qualification or a promotion. Often, the only reward is in knowing, “I did the right thing.”

It is not by accident or random choice that courage is one of the three standards the Navy has chosen to live by. Honor and commitment must be teamed with courageâboth moral and physicalâif the Navy is going to carry out its many missions and overcome the myriad challenges that arise every day.

While there have been and always will be moments when courage fails, the long history of the Navy is an impressive record of Sailors having the courage to do what is right, what is needed, what makes the difference between success and failure, what ultimately decides victory over defeat.

PBRs 105 and 99 of River Section 531 were closing rapidly on two sampans loaded down with uniformed troops in the middle of the My Tho

River. The PBRs were running at full throttle, their American flags stretched taut, great white rooster tails following close behind.

In October 1966 it was not unusual for American Sailors to be seen on the waterways of Vietnam. The U.S. Navy had expanded its traditional large-fleet, “blue-water” role to take the fight to the enemy in the “brown-water” world of the Mekong Delta and RSSZ. Using modified fiberglass recreational boats powered by jet pumps, many Sailors voluntarily left their jobs as yeomen, signalmen, and the like to “get up close and personal” with the Communists, who were using the waterways to smuggle war-making contraband and to disrupt the vital flow of rice from the paddies to the marketplace along South Vietnam's vital rivers. Small yet well-armed PBRs patrolled the jungle-lined waterways to keep them open, often boarding and inspecting junks and sampans to make sure they were legitimate commercial traffic.

On this particular day, there was no doubt that these two sampans were not commercial. Heavily armed men wearing North Vietnamese military uniforms were clearly visible in the craft. The two sampans split up; one headed for the north shore, the other toward the south. The soldiers in the sampans fired at the approaching patrol boats and were almost instantaneously answered by the staccato bark of the forward twin fifties of each PBR. The two American craft veered off after the southbound sampan. When they got close enough, they slowed down to stabilize the careening fire of their gunners, and in less than a minute they had destroyed the fleeing enemy craft. Boatswain's Mate First Class James Elliott Williams throttled up and banked the 105 in a tight turn that caused the skidding PBR to burrow nose-down into the river before dashing out across the water in hot pursuit of the other sampan. Williams was boat captain for the 105 and patrol officer in charge of both PBRs.

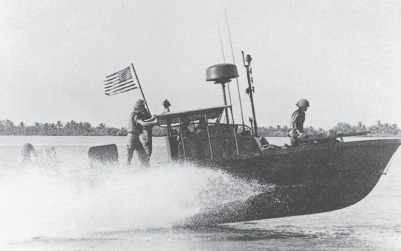

A PBR under way in the Mekong Delta. These dark green craft were a mere thirty-one feet long and were manned by a crew of four. They had no propellers; they were driven, instead, by a water-jet system that allowed them to operate in extremely shallow water. Because their fiberglass hulls provided no protection against enemy fire, speed and armament were their main defenses.

U.S. Naval Institute Photo Archive

Before the Americans could get to it, the second sampan reached the north bank of the river and disappeared into a channel too small for the PBRs. Williams knew that part of the Mekong Delta like the back of his hand, so he radioed the 99 and said in his South Carolinian drawl: “Stay with me. I know where he has to come out. We'll get 'im.” The two boats raced, prows high, to head off the sampan. A short way down the riverbank they turned into a canal. Some months before, Williams had removed all of the armor from his boat, except that which surrounded the engines, in order to get more speed and to permit the 105 to carry more ammunition. She was a fast boat flying through the canal at about thirty-five knots. The trees lining the banks were a peripheral green blur to the Sailors on the dashing craft.

As they raced around a bend in the canal, Seaman Rubin Binder, the 105's forward gunner, suddenly shouted something colorful. Before them were forty or fifty boats scattered over the canal, each carrying fifteen to twenty troops. The sampans were so full of men, they barely had two inches of freeboard remaining. It would be difficult to assess who was more startledâthe crews of the PBRs upon suddenly finding the waterway full of an enemy “fleet,” or the soldiers of the 261st and 262nd NVA regiments upon seeing two patrol craft careening around the bend and hurtling down on them.