A Short History of the World (22 page)

Read A Short History of the World Online

Authors: H. G. Wells

The Dynasties of Suy and Tang in China

Throughout the fifth, sixth, seventh and eighth centuries there was a steady drift of Mongolian peoples westward. The Huns of Attila were merely precursors of this advance, which led at last to the establishment of Mongolian peoples in Finland, Esthonia and Hungary, where their descendants, speaking languages akin to Turkish, survive to this day. The Bulgarians also are a Turkish people, but they have acquired an Aryan speech. The Mongolians were playing a role towards the Aryanized civilizations of Europe and Persia and India, that the Aryans had played to the Aegean and Semitic civilizations many centuries before.

In central Asia the Turkish peoples had taken root in what is now western Turkestan, and Persia already employed many Turkish officials and Turkish mercenaries. The Parthians had gone out of history, absorbed into the general population of Persia. There were no more Aryan nomads in the history of central Asia; Mongolian people had replaced them. The Turks became masters of Asia from China to the Caspian.

The same great pestilence at the end of the second century

AD

that had shattered the Roman Empire had overthrown the Han dynasty in China. Then came a period of division and of Hunnish conquests from which China arose refreshed, more rapidly and more completely than Europe was destined to do. Before the end of the sixth century China was reunited under the Suy dynasty, and this by the time of Heraclius gave place to the Tang dynasty, whose reign marks another great period of prosperity for China.

Throughout the seventh, eighth and ninth centuries China

was the most secure and civilized country in the world. The Han dynasty had extended her boundaries in the north; the Suy and Tang dynasties now spread her civilization to the south, and China began to assume the proportions she has today. In central Asia indeed she reached much farther, extending at last, through tributary Turkish tribes, to Persia and the Caspian Sea.

The new China that had arisen was a very different land from the old China of the Hans. A new and more vigorous literary school appeared, there was a great poetic revival; Buddhism had revolutionized philosophical and religious thought. There were great advances in artistic work, in technical skill and in all the amenities of life. Tea was first used, paper manufactured and woodblock printing began. Millions of people indeed were leading orderly, graceful and kindly lives in China during these centuries when the attenuated populations of Europe and western Asia were living either in hovels, small walled cities or grim robber fortresses. While the mind of the West was black with theological obsessions, the mind of China was open and tolerant and enquiring.

One of the earliest monarchs of the Tang dynasty was Tai-tsung, who began to reign in 627, the year of the victory of Heraclius at Nineveh. He received an embassy from Heraclius, who was probably seeking an ally in the rear of Persia. From Persia itself came a party of Christian missionaries (635). They were allowed to explain their creed to Tai-tsung and he examined a Chinese translation of their Scriptures. He pronounced this strange religion acceptable, and gave permission for the foundation of a church and monastery.

To this monarch also (in 628) came messengers from Muhammad. They came to Canton on a trading ship. They had sailed the whole way from Arabia along the Indian coasts. Unlike Heraclius and Kavadh, Tai-tsung gave these envoys a courteous hearing. He expressed his interest in their theological ideas and assisted them to build a mosque in Canton, a mosque which survives, it is said, to this day, the oldest mosque in the world.

1

Muhammad and Islam

A prophetic amateur of history surveying the world in the opening of the seventh century might have concluded very reasonably that it was only a question of a few centuries before the whole of Europe and Asia fell under Mongolian domination. There were no signs of order or union in western Europe, and the Byzantine and Persian empires were manifestly bent upon a mutual destruction. India also was divided and wasted. On the other hand China was a steadily expanding empire which probably at that time exceeded all Europe in population, and the Turkish people who were growing to power in central Asia were disposed to work in accord with China. And such a prophecy would not have been an altogether vain one. A time was to come in the thirteenth century when a Mongolian overlord would rule from the Danube to the Pacific, and Turkish dynasties were destined to reign over the entire Byzantine and Persian empires, over Egypt and most of India.

Where our prophet would have been most likely to have erred would have been in underestimating the recuperative power of the Latin end of Europe and in ignoring the latent forces of the Arabian desert. Arabia would have seemed what it had been for time immemorial, the refuge of small and bickering nomadic tribes. No Semitic people had founded an empire now for more than a thousand years.

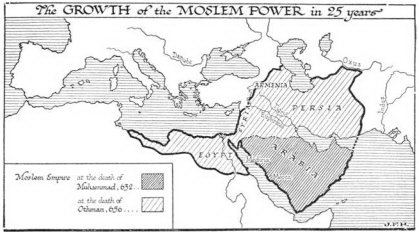

Then suddenly the Bedouin flared out for a brief century of splendour. They spread their rule and language from Spain to the boundaries of China. They gave the world a new culture. They created a religion that is still to this day one of the most vital forces in the world.

The man, Muhammad, who fired this Arab flame appears first in history as the young husband of the widow of a rich merchant of the town of Mecca. Until he was forty he did very little to distinguish himself in the world. He seems to have taken considerable interest in religious discussion. Mecca was a pagan city at that time worshipping in particular a black stone, the Kaaba, of great repute throughout all Arabia and a centre of pilgrimages; but there were great numbers of Jews in the country â indeed all the southern portion of Arabia professed the Jewish faith â and there were Christian churches in Syria.

About forty Muhammad began to develop prophetic characteristics like those of the Hebrew prophets 1,200 years before him. He talked first to his wife of the One True God, and of the rewards and punishments of virtue and wickedness. There can be no doubt that his thoughts were very strongly influenced by Jewish and Christian ideas. He gathered about him a small circle of believers and presently began to preach in the town against the prevalent idolatry. This made him extremely unpopular with his fellow townsmen because the pilgrimages to the Kaaba were the chief source of such prosperity as Mecca enjoyed. He became bolder and more definite in his teaching, declaring himself to be the last chosen prophet of God entrusted with a mission to perfect religion. Abraham, he declared, and Jesus Christ were his forerunners. He had been chosen to complete and perfect the revelation of God's will.

He produced verses which he said had been communicated to him by an angel, and he had a strange vision in which he was taken up through the Heavens to God and instructed in his mission.

As his teaching increased in force the hostility of his fellow townsmen increased also. At last a plot was made to kill him; but he escaped with his faithful friend and disciple, Abu Bekr, to the friendly town of Medina which adopted his doctrine. Hostilities followed between Mecca and Medina which ended at last in a treaty. Mecca was to adopt the worship of the One True God and accept Muhammad as his prophet,

but the adherents of the new faith were still to make the pilgrimage to Mecca

just as they had done when they were pagans. So Muhammad established the One True God in Mecca without injuring its pilgrim traffic.

In 629 Muhammad returned to Mecca as its master, a year after he had sent out these envoys of his to Heraclius, Tai-tsung, Kavadh and all the rulers of the Earth.

Then for four years more until his death in 632, Muhammad spread his power over the rest of Arabia. He married a number of wives in his declining years, and his life on the whole was by modern standards unedifying. He seems to have been a man compounded of very considerable vanity, greed, cunning, self-deception and quite sincere religious passion. He dictated a book of injunctions and expositions, the Koran, which he declared was communicated to him from God. Regarded as literature or philosophy the Koran is certainly unworthy of its alleged divine authorship.

Yet when the manifest defects of Muhammad's life and writings have been allowed for, there remains in Islam, this faith he imposed upon the Arabs, much power and inspiration. One is its uncompromising monotheism: its simple enthusiastic faith in the rule and fatherhood of God and its freedom from theological complications. Another is its complete detachment from the sacrificial priest and the temple. It is an entirely prophetic religion, proof against any possibility of relapse towards blood sacrifices. In the Koran the limited and ceremonial nature of the pilgrimage to Mecca is stated beyond the possibility of dispute, and every precaution was taken by Muhammad to prevent the deification of himself after his death. And a third element of strength lay in the insistence of Islam upon the perfect brotherhood and equality before God of all believers, whatever their colour, origin or status.

These are the things that made Islam a power in human affairs. It has been said that the true founder of the Empire of Islam was not so much Muhammad as his friend and helper Abu Bekr. If Muhammad, with his shifty character, was the mind and imagination of primitive Islam, Abu Bekr was its conscience and its will. Whenever Muhammad wavered Abu Bekr sustained him. And when Muhammad died, Abu Bekr became Caliph (successor), and with the faith that moves mountains, he set himself simply and sanely to organize the subjugation of the whole world to Allah â with little armies of 3,000 or 4,000 Arabs â according to those letters the prophet had written from Medina in 628 to all the monarchs of the world.

The Great Days of the Arabs

There follows the most amazing story of conquest in the whole history of our race. The Byzantine army was smashed at the battle of the Yarmuk (a tributary of the Jordan) in 634;

1

and the Emperor Heraclius, his energy sapped by dropsy and his resources exhausted by the Persian war, saw his new conquests in Syria, Damascus, Palmyra, Antioch, Jerusalem and the rest, fall almost without resistance to the Moslem. Large elements in the population went over to Islam. Then the Moslem turned east. The Persians had found an able general in Rustam; they had a great host with a force of elephants; and for three days they fought the Arabs at Kadessia (637) and broke at last in headlong rout.

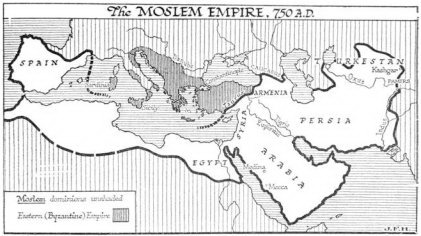

The conquest of all Persia followed, and the Moslem Empire pushed far into western Turkestan and eastward until it met the Chinese. Egypt fell almost without resistance to the new conquerors who, full of a fanatical belief in the sufficiency of the Koran, wiped out the vestiges of the book-copying industry of the Alexandria Library. The tide of conquest poured along the north coast of Africa to the Straits of Gibraltar and Spain. Spain was invaded in 710 and the Pyrenees mountains were reached in 720. In 732 the Arab advance had reached the centre of France, but here it was stopped for good at the battle of Poitiers and thrust back as far as the Pyrenees again. The conquest of Egypt had given the Moslem a fleet, and for a time it looked as though they would take Constantinople. They made repeated sea attacks between 672 and 718,

2

but the great city held out against them.

The Arabs had little political aptitude and no political experience, and this great empire with its capital now at Damascus,

which stretched from Spain to China, was destined to break up very speedily. From the very beginning doctrinal differences undermined its unity. But our interest here lies not with the story of its political disintegration but with its effect upon the human mind and upon the general destinies of our race. The Arab intelligence had been flung across the world even more swiftly and dramatically than had the Greek a thousand years before. The intellectual stimulation of the whole world west of China, the break-up of old ideas and development of new ones, was enormous.

In Persia this fresh excited Arabic mind came into contact not only with Manichaean, Zoroastrian and Christian doctrines, but with the scientific Greek literature, preserved not only in Greek but in Syrian translations. It found Greek learning in Egypt also. Everywhere, and particularly in Spain, it discovered an active Jewish tradition of speculation and discussion. In central Asia it met Buddhism and the material achievements of Chinese civilization. It learnt the manufacture of paper â which made printed books possible â from the Chinese. And finally it came into touch with Indian mathematics and philosophy.

Very speedily the intolerant self-sufficiency of the early days

of faith, which made the Koran seem the only possible book, was dropped. Learning sprang up everywhere in the footsteps of the Arab conquerors. By the eighth century there was an educational organization throughout the whole âArabized' world. In the ninth learned men in the schools of Cordoba in Spain were corresponding with learned men in Cairo, Bagdad, Bokhara and Samarkand. The Jewish mind assimilated very readily with the Arab, and for a time the two Semitic races worked together through the medium of Arabic. Long after the political break-up and enfeeblement of the Arabs, this intellectual community of the Arab-speaking world endured. It was still producing very considerable results in the thirteenth century.

So it was that the systematic accumulation and criticism of facts which was first begun by the Greeks, was resumed in this astonishing renascence of the Semitic world. The seed of Aristotle and the Museum of Alexandria that had lain so long inactive and neglected, now germinated and began to grow towards fruition. Very great advances were made in mathematical, medical and physical science. The clumsy Roman numerals were ousted by the Arabic figures we use to this day and the zero sign was first employed. The very name âalgebra' is Arabic. So is the word chemistry. The names of such stars as Algol,

Aldebaran and Boötes preserve the traces of Arab conquests in the sky. Their philosophy was destined to reanimate the medieval philosophy of France and Italy and the whole Christian world.

The Arab experimental chemists were called alchemists, and they were still sufficiently barbaric in spirit to keep their methods and results secret as far as possible. They realized from the very beginning what enormous advantages their possible discoveries might give them, and what far-reaching consequences they might have on human life. They came upon many metallurgical and technical devices of the utmost value; alloys and dyes, distilling, tinctures and essences, optical glass; but the two chief ends they sought, they sought in vain. One was âthe philosopher's stone' â a means of changing the metallic elements one into another and so getting a control of artificial gold, and the other was the

elixir vitae

, a stimulant that would revivify age and prolong life indefinitely. The crabbed, patient experimenting of these Arab alchemists spread into the Christian world. The fascination of their enquiries spread. Very gradually the activities of these alchemists became more social and co-operative. They found it profitable to exchange and compare ideas. By insensible gradations the last of the alchemists became the first of the experimental philosophers.

The old alchemists sought the philosopher's stone which was to transmute base metals to gold, and an elixir of immortality; they found the methods of modern experimental science which promise in the end to give man illimitable power over the world and over his own destiny.