A Summer Bright and Terrible

Read A Summer Bright and Terrible Online

Authors: David E. Fisher

Tags: #Historical, #Aviation, #Biography & Autobiography, #Military, #History, #World War II

A Summer Bright and Terrible

Winston

Churchill, Lord Dowding, Radar, and the Impossible Triumph of the Battle of

Britain

David

E. Fisher

Shoemaker

&

Hoard

Copyright © 2005 by David E. Fisher

All rights reserved. No part of this book

may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission

from the Publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical

articles and reviews.

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fischer, David E., 1932—

A summer bright and terrible: Winston

Churchill, Lord Dowding, Radar, and the impossible triumph of the Battle of

Britain / David E. Fisher, p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references. isbn

(10) 1-59376-047-7 (alk. paper) isbn (13) 978-1-59376-047-2

1. Britain, Battle of, Great Britain, 1940.

2. Air warfare—History—20th century. 3. Dowding, Hugh Caswall Tremenheere

Dowding, Baron, 1882—1970. 4. Churchill, Winston, Sir, 1874—1965. I. Title.

D756.5.B7F57 2005 94o.54’2ii—dc22

2005003765

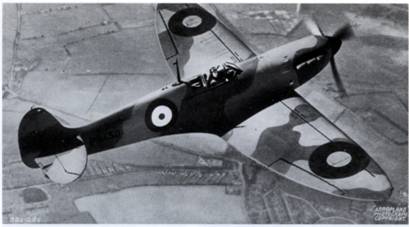

Gallery illustrations: map by Mike Morgenfeld;

Spitfire from postcard by Valentine & Sons, Ltd.; the Hurricane courtesy of

British Aerospace, Military Aircraft Division; radar towers courtesy of Gordon

Kinsey, author of

Bawdsey

(Terence Dalton Limited); Douglas Bader

courtesy of Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund; Keith Park from the collection of

the Walsh Memorial Library, MOTAT, New Zealand, also courtesy of Dr. Vincent

Orange; the Bristol Beaufighter courtesy of British Aerospace, Bristol

Division; Dowding statue photo by Lisabeth DiLalla. Every attempt has been made

to secure permissions. We regret any inadvertent omission.

Book design and composition by Mark

McGarry Set in Fairfield

Printed in the United States of America

Shoemaker Hoard

An Imprint of Avalon Publishing Group, Inc.

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 987654321

This

book is for Satchel Rhain and Bram Jakob

I was simply frightened that we should

lose. It was a perfectly straightforward fear, instinctive and direct. The

summer of 1940 was an agony for me: I thought that the betting was 5:1 against

us. . . . I felt that, as long as I lived, I should remember walking along

Whitehall in the pitiless and taunting sun . . . in the bright and terrible

summer of 1940.

Lewis

Eliot,

in

The

Light and the Dark,

by C. P. Snow

Contents

| Preface |

Part One | The Winter of Discontent |

Part Two | Springtime for Hitler |

Part Three | The Long Hot Summer |

Part Four | Autumn Leaves |

| Epilogue |

| Acknowledgments |

- Preface

- Part One - The Winter of Discontent

- Part Two - Springtime for Hitler

- Part Three - The Long Hot Summer

- Part Four - Autumn Leaves

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

In England the summer of 1940 was the

sunniest, driest, most glorious summer in living memory. In that bright and

terrible summer Hitler’s Germany lay spread like a galloping cancer across

Europe. Austria and Czechoslovakia had been swallowed, Poland destroyed,

Belgium, Holland, and France enveloped and subjugated in a new form of warfare,

the Blitzkrieg. Twenty-five years earlier, the German and French armies had

lain supine in trenches for four years, gaining or losing yards at a time. Now

suddenly the armoured Panzer Korps came thundering through the French lines with

dive-bombing Stukas blasting a path for them, and within a few weeks, the

continental bastion of democracy had fallen.

The British army escaped at Dunkirk, but the

soldiers who returned to England were no longer an army. They were a rabble

without guns or ammunition. They had left their tanks, their mortars, their

machine guns and their cannon behind on the bloody beaches of France. As the

summer blossomed, their future wilted.

Winston

Churchill was appointed prime minister on the day France was invaded, and now

he stood like a lion roaring. “We shall fight them on the beaches . . . we

shall fight in the fields and in the streets. . . . We shall

never

surrender.”

It was an empty boast. If once the Wehrmacht

crossed the

English Channel,

there was nothing in England to fight them with. Old men and young boys were

parading around in the Home Guard with broomsticks for weapons, prompting Noel

Coward to write his clever ditty ending with the refrain “If you can’t provide

us with a Bren gun, the Home Guard might as well go home.” It was tuneful, it

was clever, it was pathetic.

There were no Bren guns.

There was only the Royal Air Force.

All Hitler’s hordes had to do in order to rule

all of Europe was cross twenty miles of seawater, but there’s the rub. For as

soon as they clambered onto their invasion barges, which were piling up along

the French coast, and set sail, the Royal Navy would come steaming out of its

port on the northwest of Scotland and sweep them aside, shattering the barges

and tossing the army into the waters of the English Channel.

But wait. Why was the Royal Navy huddled in the

west in the first place? Its normal home port was Scapa Flow, in the north

-

eastern Orkney Islands, positioned

perfectly to disgorge the battleships that would sink the Wehrmacht. The answer

to this embarrassing question was the Luftwaffe.

In the First World War, the battleship had been

the lord of the sea. In this new conflict, it was already apparent that the

lord had abdicated: The airplane was the definitive weapon. Afraid of the

German bombers, the navy had deserted its bastion and retreated west, beyond

the range of the Nazi planes. If the invasion began, the Royal Navy would

indeed come steaming forth in all its bravery and majesty, but they would come

steaming forth to their deaths. It would be the Charge of the Light Brigade all

over again, an outmoded force gallantly but uselessly falling to modern

technology. Just as the horse-mounted officers of the Light Brigade were mowed

down in their tracks by machine guns and cannon, the

battleships and cruisers of the navy would sink under the bombs of

the Stukas.

Unless, of course, the Royal Air Force could

clear the skies of those Stukas.

And so it came down to this: If the Luftwaffe could

destroy the Royal Air Force, the German bombers could destroy the Royal Navy

and nothing could stop the invasion. Once ashore in England, the Wehrmacht

would roll through the country more easily than it had in France, where it had

been opposed by a well-armed army. Churchill might roar and bellow, but the

British would not fight them on the beaches and in the streets, for they had

nothing left to fight them with. The story that as Churchill sat down in the

House of Commons after his famous rodomontade, he muttered, “We’ll beat them

over the heads with beer bottles, because that’s all we’ve bloody got left,” is

probably untrue but it does reflect the truth of the moment.

As the days of that terrible summer rolled

on, America’s eyes turned with a growing anxiety to the tumult in the skies

over England. Americans had long thought of the Atlantic Ocean as an invincible

barrier between themselves and Europe, but if Hitler defeated England and

gained control of the world’s strongest navy, the Atlantic would become an open

highway to the U.S. eastern seaboard.

And to most observers, Hitler’s victory seemed

certain. JFK’s father, Joseph Kennedy, ambassador to England, came home with

his family and proclaimed that England was finished. (The joke going the rounds

in London: “I used to think that pansies were yellow until I met Joe Kennedy.”)

At America First rallies around the United States, Charles Lindbergh was

singing the praises of the German Luftwaffe, calling it invincible, anointing

its fighter planes as the world’s best by far. Hitler could not be defeated, he

shouted, and Congress listened. (And a Hitler victory wasn’t a bad thing, he

went on. The Nazis were clean, efficient, and moral, aside from that

little business with the Jews. And you

couldn’t really blame them for that, he whispered.)

Even as Lindbergh was arguing that Germany’s

air force was unstoppable, President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced that

Luftwaffe bombers would soon be able to fly from bases in West Africa to attack

cities as far west as Omaha, Nebraska. Though this technical accomplishment was

a fantasy, something developing in the Peenemunde laboratory of Werner von

Braun was not. It was an engineering feat no one yet knew about: an improved

version of the as-yet-unveiled V-2 rocket. Named the V-10, it would be a true

intercontinental ballistic missile, which could reach anywhere in America. And

just the year before, nuclear fission had been discovered—in Berlin.

So the stage was set. In July of

that summer, when the vaunted German air force began its aerial assault as a

prelude to a cross-Channel invasion, the Allies’ only hope lay in the few

fighter pilots of the Royal Air Force and in the resolute, embattled man who

led them: not Churchill, but the man who had fought Churchill and nearly every

other minister and general in a series of increasingly bitter battles through

the pre

-

war years; who without

scientific training directed the energies of England’s vast scientific aerial

establishment; who had defied the fierce arguments of Churchill’s own

scientific adviser and instead backed and promoted the single technical

device—radar—that would provide the backbone of Britain’s aerial defence and

the slim margin of victory.

Rather incredibly, this was also a man whose

mind broke from the strain at the height of the battle, who talked to the

ghosts of his dead pilots, but who nevertheless was able to keep another part

of his mind clear enough to continue making the daily life-and-death decisions

that saved England. The man whose name today is practically unknown: Hugh

Caswall Tremenheere Dowding, Air Chief Marshal of the Royal Air Force,

Commander in Chief of Fighter Command. Lord Dowding, First Baron of Bentley

Priory.

Lord Dowding

The air defence of England, showing the responsibilities

of Fighter Command Groups, with each Group divided into Sectors. Also shown are

the main airfields in each sector.

Lord Trenchard

The Spitfire

The Hurricane

Radar Towers

Bentley Priory, outside Dowding’s office