A Summer Bright and Terrible (2 page)

Read A Summer Bright and Terrible Online

Authors: David E. Fisher

Tags: #Historical, #Aviation, #Biography & Autobiography, #Military, #History, #World War II

Professor Lindemann

Douglas Bader, lifting his leg to clamber into his

Spitfire

Keith Park

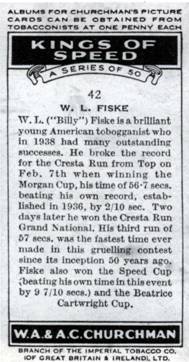

Billy Fiske, on a British cigarette card from the 1930s

The Bristol Beaufighter

Dowding’s office at Bentley Priory. The uncluttered

desk is just as he kept it day by day.

The plotting table at Fighter Command headquarters,

showing the incoming plots as they were on September 15, 1940. On the wall is the

listing of fighter squadrons in No. 11 Group, indicating whether they are at

readiness, in the air, or available.

Dowding’s statue in front of the Church of St. Clement

Dane in the Strand, the “official” RAF church.

One

It is Wednesday, September 6, 1939, three

days after the declaration of war. On the crest of a hill overlooking the

London suburb of Stanmore, amid a forest of cedar trees and blossoming

vegetable gardens, stands one of the lesser stately homes of England, Bentley

Priory. The site goes back in history to the year A.D. 63, when Queen Boadicea,

defeated after a furious struggle against the invading Romans, took poison and

was buried there. In the twelfth century the priory was established, but today

the prayers of Air Marshal Dowding, aka “Stuffy,” head of the Royal Air Force’s

Fighter Command, are to a different God as he stands above a different kind of

altar. He is in an underground bunker, seated on a balcony next to King George

VI, looking down at the main room and at the altar: a twenty-foot square table

on which is etched a map of the southeast corner of England.

Just after ten o’clock that morning, a black

marker was placed on the table, indicating a radar warning of incoming

aircraft, and a flight of Hurricanes was scrambled. A red marker, indicating

the British fighters, was placed in position. Dowding nodded to His Majesty;

this was how the system worked.

He explained that a chain of radar stations had

been set up along the southern and eastern coasts of England. (He actually used

the

words “radio direction

finding stations” since the acronym

radar

—for radio detecting and

ranging—was a later American invention.) These could spot incoming airplanes

while they were still out of sight over the Channel, or even still over France.

The information was passed by a newly constructed series of telephone lines

directly here to Bentley Priory, and simultaneously to the pertinent Group

Sector commands.

The entire air defence of Great Britain had

been organized into four Fighter Groups. No. 11 Group covered the south

-

eastern corner, with No. 12 Group to its

immediate north. Bombers coming from Germany would enter No. 12 Group’s

jurisdiction, which was expected to be the primary battleground. But now with

France fallen to the enemy, the French aerodromes were available to the

Luftwaffe. These were closer to England and so would be the primary bases for

the German attacks. Because a direct line from the French airfields to London

would bring them into No. 11 Group, No. 12 Group would now be expected to

provide mostly backup. To the west, No. 10 Group would provide more

reinforcements, while No. 13 Group in the far north would guard against

surprise attacks and provide training for replacements.

The system had received its first test just

moments after the declaration of war. On Sunday, September 3, 1939, Prime

Minister Neville Chamberlain addressed the nation by radio: “I am speaking to

you from the Cabinet Room at Number 10, Downing Street. This morning the

British Ambassador in Berlin handed the German Government a final Note stating

that, unless we heard from them by 11 o’clock that they were prepared at once

to withdraw their troops from Poland, a state of war would exist between us. I

have to tell you now that no such undertaking has been received, and that

consequently this country is at war with Germany.”

He spoke at 11:15 a.m. Ten minutes later, the

air-raid sirens sounded over London.

The nation was dumbfounded. For the past six or

seven years,

they had been

warned that the next war would be decided in the space of a few hours as

bombers would blast cities into smithereens, but they hadn’t believed it. Now

they streamed into the basements of the largest buildings, which displayed

hastily printed signs, air raid shelter, as uniformed bobbies on bicycles raced

down the streets with large placards hanging from their necks: air raid! take

shelter!

In the Operations Room at Bentley Priory, a

single black marker was placed on the table, and at Biggin Hill aerodrome, a

telephone rang. The airman on duty yanked it from its cradle, listened for a

moment, and then yelled out the window, “Scramble! Blue section, scramble!”

Three pilots raced across the grass to their

planes as the mechanics started the engines. In less than a minute, the

Hurricanes were tearing across the aerodrome and screeching into the air.

Fifteen minutes later, they came floating back

to earth without having fired their guns. The blip on the radar screens turned

out to be a small civilian airplane in which an assistant French military

attache, Captain de Brantes, was flying back to London from a weekend of

partying in Paris. Well, some things are more important than a declaration of

war, and he hadn’t been paying attention. Nor had he bothered to file a flight

plan. The radar beams saw him coming, the Controllers listed him as “unidentified,”

and the air-raid sirens went off.

Dowding hadn’t been annoyed. In fact, he was

rather pleased. The incident had provided an excellent surprise test of the

system. And the system had worked. Earlier that year, someone had asked him if

he was prepared for war. What would he do when it came, was the question, “Pray

to God, and trust in radar?” Dowding had answered, in his stuffy manner, “I

would rather pray for radar, and trust in God.” Now it seemed that his prayers

had been answered.

At least it seemed that way until that night,

when, as the

Times

of London reported, “Air raid warnings were sounded

in the early

hours of the

morning over a wide area embracing London and the Midlands.”

And yet, again, no bombs were dropped. The

Times

went on to say that “the air-raid warnings were due to the passage of

unidentified aircraft. Fighter aircraft went up and satisfactory identification

was established.”

But this account was not only wrong; it was

total nonsense. In 1939, it was impossible even to locate aircraft at night,

let alone identify them. The daytime “raid” had pleased Dowding; the night-time

raid worried him. Well, actually, it scared the hell out of him. Because

nothing had happened.

There were no German aircraft flying over

England that night. There were no aircraft of any kind up there. Yet just

before 2:30 a.m., the radar station at Ventnor picked up a plot coming in over

the waters toward the coast. At Tangmere aerodrome, No. 1 Squadron was at

readiness when the telephone rang. Three Hurricane fighters were sent off to

intercept. They searched until their fuel ran low, and then other sections were

sent off. None of them found anything.

It wasn’t that Dowding wanted the Germans to

bomb England, but when his system said there were bombers there, he desperately

wanted the bombers to be there! Nothing was worse than nothing. Nothing in the

air when radar said something was there—that was frightening. If he couldn’t

trust radar, there wasn’t much use in praying to God for anything else.

There wasn’t anything else.

Now, three days later, a new blip on the

radar screen is observed: More enemy aircraft, and another black marker is

added to the table. The Bentley Priory Controller scrambles a whole squadron to

deal with it. But no sooner are they airborne when another blip appears on the

screen. More squadrons are scrambled.

And still more. Each squadron of Spitfires or

Hurricanes seems to be followed by another formation of German bombers. One by

one, more and more squadrons are sent up. Dowding begins to look distinctly

worried. On the wall are lists of the RAF squadrons headed by green or red

lights: On Reserve, or Committed. As another red marker is placed on the table,

the last green light changes to red.

By this time, every single squadron east of

London has been scrambled, and the system is overloaded: The Controllers have

too many aircraft aloft, and neither the Controllers nor the radio

telecommunications link to the aircraft nor the telephone lines from the radar

stations can handle the traffic. The king of England is accustomed to

embarrassing situations; he says nothing, merely watches as the system Dowding

had carefully explained to him slips into chaos. The monarch glances at the

wall, sees that all the lights are now red, and understands that every British

fighter is now in the air. He remembers the warnings of Armageddon from the

air, the prophecies that the coming war will be won or lost on the first day.

He wonders if this will be the last day for

poor England.

The battle rages for an hour as blips fill the

radar screens, from mid

-

channel

up to London and down again throughout Kent. Fighter contrails fill the sky,

punctuated by the black puffs of antiaircraft bursts. A squadron of Spitfires

dives on a formation of Messerschmitts (Me’s) and shoots down two as the

British planes zoom past and climb back up into the sun. When the Brits look

back, the Me’s are gone.

There is no letup on the radar screens, but

after an hour of fighting on emergency boost, the British planes are running

low on fuel and, despite pleas from the Controllers, who are trying to direct

them onto new plots, the pilots are forced to return to their aerodromes. At

Bentley Priory the Controllers turn one by one to Dowding, but there is nothing

he can say, nothing he can do. Any further raids will sweep in un-attacked to

catch all his forces on the ground.

When war was first declared, Dowding had gone on the radio to

promise the people he would protect England from aerial attack.

It looks like he was wrong.

But no further raids materialize. As the

fighters return to base, the enemy plots fade away too, and soon the skies are

clear and the radar scopes empty. The WAAFs (Women’s Auxiliary Air Force

members), emotionally and physically exhausted, take off their headphone sets

and lean wearily against the map tables. The Controllers sit quietly by their silent

telephones, the king scratches his ear, and Dowding begins to breathe again.

Army units quickly disperse throughout the

battle area, searching for bomb damage and for airplane wrecks, trying to

assess the damage done by and to the Luftwaffe. Meanwhile, back at the

aerodromes, the Squadron Intelligence Officers interview the returning pilots.

At first there is jubilation. The fighters of

the Royal Air Force seem to have won a decisive victory. No factories or

airfields have been bombed. No houses have been destroyed. In fact, no bomb

craters are found.

The jubilation turns to wonder. No bomb craters

at all? Strange . . .

Stranger still, no German airplane wrecks are

found. Although the antiaircraft batteries are sending in report after report

of sightings on which they had fired, in all of England only two planes seem to

have been shot down, and both of these are British Hurricanes. Of the RAF

fighters, only one Spitfire formation reports attacking anyone, and only one

squadron of Hurricanes was attacked. The Spitfires report shooting down two of

the enemy.

The Intelligence Officers begin to feel a bit

uneasy. One of the downed Hurricane pilots reports that the German

Messerschmitts that attacked him were painted, not with swastikas or crosses,

but with roundels similar to those the RAF uses. The crews in the field call in

that the two wrecks are riddled with machine-gun bullets. Air Vice-Marshal C.

H. N. Bilney asks them to look again. While the British fighters have only

machine guns, the Messerschmitts have

cannon as well. The report comes back quickly: Small holes only, no

large cannon holes are seen. Bilney drives out to take a look at one of the

wreckages. It is true: The downed Hurricane shows only small holes. “Knowing

that German bullets had steel cores as opposed to the lead cores of ours,” he

reports to Dowding, “I got a piece of wood, put some glue on one end and fished

around in the wing for bullet fragments. I soon found quite a lot of lead.”

And the jubilation turns to consternation. What

the bloody hell happened up there in the sky?

What happened was confusion amid the

catastrophic collapse of the entire defence system, due to a fault that had

been previously recognized but not totally assimilated. The radar transmitting

antennae radiated their radio signals both forward and backward simultaneously,

and couldn’t tell from which signal—forward or backward—any received echoes

were obtained. That is, an aircraft directly east or directly west of a radar

station would give exactly the same blip. The only solution was to try to

electronically black out the backward emissions. The radar wizards thought they

had done that.

They hadn’t. Somewhere to the west, behind the

coastal radar towers, a British airplane had taken off. The radar operators

thought the towers were looking eastward, over the Channel, but somehow the

towers picked up the airplane behind them. Naturally it was reported as an

unidentified aircraft coming in toward England, and a section of Hurricanes was

sent off to intercept it. But as they rose into the air from their aerodrome

behind

the coastal radar towers, they were picked up on the scopes and plotted as more

incoming aircraft

in front of

the towers—as enemy aircraft coming in

across the sea.

A whole squadron of Hurricanes was scrambled to

meet this new “threat.” And this squadron was also picked up on radar as an

enemy formation, a bigger one this time. Two squadrons of Spitfires were

scrambled, which were in turn identified as more Germans . . .