A Tale Without a Name (16 page)

Read A Tale Without a Name Online

Authors: Penelope S. Delta

“So why don’t you write to your children to come back?” said the Prince to them, for he was never far from their midst.

And those who knew their letters sat down and wrote. And those who did not know how to read or write asked the schoolmaster, who made out for them a letter addressed to their child, or their brother, or their father, and little by little some of those who had left came back, and more weapons and more clothes were needed, and more food.

The Prince went then to the capital and to the villages, and he talked to the women and told them:

“Why are you sitting idle, cooped up in your homes? Your men are at the camp, and working the fields and laying

down new roads, building ships, mills and storehouses. Why don’t you come too, and help with the preparation of the soup, sew clothes so that your men will have things to wear come winter?”

“And where are we to find the fabric?” the women asked.

“And where are we to find the yarn?”

“You ought to spin the yarn yourselves!”

“Oh, but Prince!” replied the women. “We are but poor folk, we have no sheep. Where shall we find the wool?”

At that, the Prince opened up the precious leather purse of his money belt, and took out a few florins; he then sent Polycarpus together with one or two soldiers to the kingdom of the King the Royal Cousin to buy lambs and sheep.

And when they had brought back the flock, the Prince ordered that they be sheared and that the wool be distributed among the women so they might spin it and weave it and then cut the fabric to make clothes.

He also summoned all the girls and instructed them how to milk the ewes, and under the guidance of Mistress Wise they learnt how to churn butter and make cheese, salt them and store them for the winter when the snows would arrive.

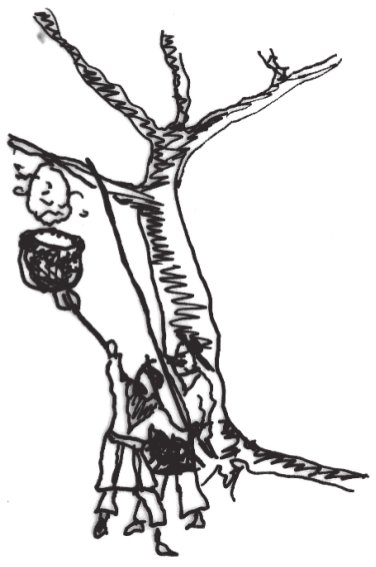

One day, as he was walking through the woods, the Prince saw hanging from a branch an entire beehive, like a big heavy bunch of grapes. He then had the idea of making honey, by assembling together in skeps the bees scattered here and there.

So he took a few big, sturdy reed baskets, and with some soldiers he went around the ravines and the plains and gathered from the tree hollows and the rocks as many bee colonies as he could find, and he brought these back and placed his reed baskets by the entrance of the wood.

And the bees produced so much honey that the Prince decided to harvest it and put it in his storehouses for the winter.

But how was he to get hold of the honeycombs?

“Fumigate the hives with sulphur, my lord,” said a lad who had just come back from abroad. “The bees will die, and then you can harvest your honey at your leisure. That’s how the Franks do it in their land.”

“Why should we kill the bees?” replied the Prince. “It would be quite a shame, now, wouldn’t it? We must increase their numbers, on the contrary.”

And turning a full skep upside down, he covered it with a large empty basket, and with a few light taps on the outside of the full hive he drove all the bees away and into the empty basket, which he then covered once more, and placed it where the skep had stood previously.

“This is how we can harvest the honey easily, without killing the precious workers who produced it,” said the Prince.

He strained the honey into earthenware jars, and he gave the beeswax away, to be melted into thick candles, so they could have light during the winter, when the days would grow short.

Several months went by, the crops matured, and the soldiers who were also farmers harvested them and put them in the storehouses built by the soldiers who were also builders.

And everyone who owned a vineyard received an order from the Prince to prune the vine roots neatly and to treat them with sulphur, so they might destroy the aphids that for years now had ravaged the plants, on which the clusters of sour grapes would then rot without ripening.

The soldiers who were also woodsmen had been so industrious that although seven ships were now navigating the river northwards as well as southwards, great stacks of timber still remained, piled up by the riverbanks, and the master builder no longer had the time to use it all, and to drive his nails into the wood.

The Prince saw the heaped logs taking up all this space and it occurred to him that he could find good use for

them at once. He had the men load them one day onto three of the ships, and gave orders to Polycarpus to go with some of the soldiers to the nearby kingdom of the King the Royal Cousin.

And while four ships were keeping watch over the river, for the sake of safety, the other three unfurled their sails and set off for the kingdom of the King the Royal Cousin, looking most splendid and majestic.

This monarch was greatly mystified when he was told of this, and he asked to know what was going on with the Fatalists, who were buying sheep and selling timber. Polycarpus merely smiled, however, took the florins, and returned with the three ships to hand the florins to the Prince, who put them overjoyed in the purse of his leather money belt for safe keeping; they were to be used for the upcoming needs of the state.

Thus the winter came, the leaves fell off the trees, the birds flew away to warmer lands, the beasts of the forest hid themselves and the land was covered with snow.

Then the Prince opened up his storehouses, took out the grain, and distributed it to the villagers who carried it to the mills; once ground and milled, they distributed the flour to the women who kneaded it and made bread.

The Prince shared his crops, and so the winter passed and no one had to face hunger.

The children learnt to read and to work, they learnt to shoot arrows and to throw the spear.

I

N THE MEANTIME

, however, the King the Royal Uncle had recovered his health.

He sought to reassemble his army, but there was not a single soldier in sight, nor could he track them down any longer.

The blackest melancholy seized hold of him then. He lost his sleep, and he fumed and fretted so much that he could not swallow even a morsel of food.

Seething with rage and tearing at his hair, he crossed the border back into his own land; and once he had regained his capital, he cut off his general’s head, because, he claimed, he had deserted the field of battle without requesting permission.

That, however, did little to cure him of his melancholy.

And so he summoned next the humpbacked and

bandy-legged

jester of King Witless, who had found refuge in his palace, having first consumed in feasting and in frolics all the money that he had made for himself by selling the

jewels he had stolen from the King of the Fatalists. The King the Royal Uncle commanded the jester to dance before him and to make him laugh.

The jester, however, thanks to the lavish life he had been enjoying, had unlearnt how to dance and how to act the fool; and because of all the rich food that he had been greedily consuming, he was now enormously fat. So that when he tried to dance before his new master, his crooked little legs got into a tangle and he fell panting on the floor.

“What a complete idiot you are!” yelled the King the Royal Uncle in wild frenzy. “You are not even funny any longer! Why should I go on feeding you, vile and ugly as you are?”

And he drew his sword and lopped off the jester’s head.

He then summoned his officers; and with terrible threats he ordered them to raise instantly a most fearsome army, cross the border yet again, and lay his nephew’s land to waste.

Yet they no longer had any weapons, since the soldiers had abandoned them on the battlefield during their flight. Nor was it so very easy to gather together the men, who had by now scattered to every corner of the kingdom, each of them holed up in his village.

And so it came to pass that, whether he liked it or not, the King the Royal Uncle was forced, for all his seething rage, to postpone his vengeance until a new army might be raised.

The Prince, who was being kept informed of all enemy movements by his secret envoys, ordered a unit of soldiers to leave the camp and proceed all the way to the border, and there erect a mighty citadel, right up on the very top of the rocks, in the exact place where the ruins of the castle built by his grandfather, Prudentius I, could still be seen.

The soldiers carried there provisions for their maintenance; and since the women had gone with them, to knead bread and to cook food, they also had to build some wooden huts to shelter them.

The water, however, seeped in through the cracks between the logs when it rained, and the blustering wind froze them to the bone.

The men therefore decided to build stone cottages, and at nightfall, after their work at the citadel was finished, they would work little by little on their cottage.

And so it came to pass that when it was springtime once again, an entire village had spread at the feet of that great rock, and the Prince ordered them to build a second citadel on the rock next to it, to offer it protection, just at the very spot where there remained the ruins of another old fortress of Prudentius I.

Once some shacks had been erected there as well, the Prince found himself obliged, in order to guarantee their safety, to build a third citadel, and then a fourth, and so on, all along the frontier.

In the meantime, the seven ships had become fifteen, and a good half of these kept sailing away, loaded with timber.

Polycarpus kept coming back with ever more florins, so that they could no longer fit in the purse of the leather money belt, and the Prince had to order a heavy iron coffer with a sturdy lock from Miserlix; he put the florins inside, and kept the coffer under lock and key in the palace cellar.

Knowledge and Mistress Wise did after all accept the Prince’s invitation to come up to the palace and live there, for with the very first rain showers, their tree hollow had become uninhabitable.

Together with Knowledge and Mistress Wise, Jealousia and Spitefulnia had also returned to the palace. Since they had been to stay with Knowledge, however, and had shared her work, they had completely unlearnt how to quarrel; and so it happened that when they entered the tower again and saw their rooms with the wrecked furniture strewn everywhere, and the urge came back to them to squabble, they realized all of a sudden that they had forgotten what words to use in order to begin, and they remained for an instant frozen and motionless, staring at one another.

Knowledge, who had only just arrived at that moment herself, sent one of them off to milk the cow, and the other away to weave reed baskets, so they might keep the chickens inside until the henhouse had been rebuilt; and so it came to pass that the two sisters missed their very last chance to resume their old quarrelsome ways.

As a result, tranquillity and soothing silence reigned everywhere in the palace. There was never any screaming to be heard.

The King read his paper in peace every evening, and Knowledge had taught Queen Barmy how to knit stockings; in this way, she managed to win over the King’s heart—for he had grown weary, he said, of stepping all day on the bits of broken glass and snippets of tin that the Queen kept scattering everywhere on the floor with all the frills and trinkets she strove to make.

Spring returned, the trees were once again covered with green leaves, the strawberries pushed through, ripening nicely, and the wild rocket grew plentiful everywhere; the birds came back from their wintering places, and hunting was resumed. The farmer-soldiers sowed anew, not only the fields of the previous year, but new ones as well, and agriculture was re-established throughout the realm.

From the camp to the capital, and from there again to the smithy of Miserlix, there was now a long, wide and well-paved road.

The Prince ordered then the woodsmen-soldiers to stop cutting down the trees from the forests along the river, and to begin felling those in the wooded thickets close to Miserlix’s smithy. And there, where they had felled many trees, he had them plant young saplings, so that these might grow and be useful at a later time.

With the very last load of timber that the Prince had sent out to be sold to the King the Royal Cousin, the Prince instructed Polycarpus to buy horses, so they could transport the logs more easily to the riverbank.

Together with the horses, he ordered also chickens and ducks, geese and goats. And once the ships returned, he distributed the poultry and the goats to the villages, with the order that each householder should build a pen and a coop. And every day he travelled, now to this village, now to the next, to see whether the villagers were looking after their livestock, and whether they had followed his instructions.

As soon as the village women saw the skilfully built pens and the tidy henhouses, they felt the urge to have each a small garden of their own, where they could grow their vegetables, instead of having to go all the way to the woods every day to collect wild greens.

And next to the garden, they also felt the urge to spruce up their own little cottages. And those whose sons were still abroad had the schoolmaster write them a letter to tell them to come back.

The schoolmaster wrote a letter, which read as follows:

Come back, my child, the good days have returned to our land, everyone has come home, and is earning his bread here today; you alone are still left withering away on your lonesome in foreign parts!

The women were deeply touched when the schoolmaster read this out to them, and each one wanted this letter for her own child, because, as they said, it was so very lovely! The schoolmaster therefore wrote out the same letter for all, and the letters were sent out.

The youths who were still abroad came back to their villages, young Penniless amongst them; seeing everyone else’s vineyard green and thriving, he too applied himself to the task of pruning his climbing vine and cultivating his small garden.

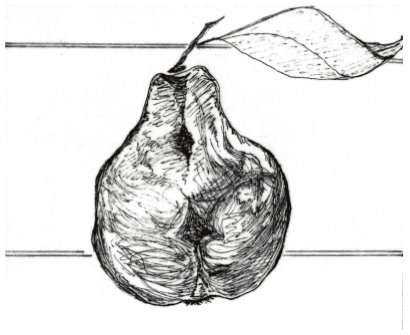

After the example of old Penniless, his neighbour too planted a climbing vine. The other neighbours saw this, and they too planted theirs. Those who had pruned and treated their vineyards with sulphur the previous summer had such a bounteous harvest of grapes that they loaded ships, and sent the grapes to be sold in the kingdom of the King the Royal Cousin.

The beehives had multiplied. They collected the honey in earthenware jars, and together with the grapes they had it all sent abroad to be sold.

“What on earth is going on in the kingdom of those Fatalists?” asked once again the King the Royal Cousin. “They buy lambs and horses, for which they pay with golden florins, they sell mountains of timber and grapes and honey. Could it be that the Regent, my cousin, has finally snapped out of his slumber?”

Polycarpus merely smiled, however, as he had done before, and did not speak; he simply took the florins and left with the ships.

His Majesty then sent for his High Chancellor and told him:

“You are to go to the kingdom of the Fatalists, and travel to its every corner. Afterwards you are to come

to me and give me a full account of what you did and did not see.”

The High Chancellor went; and he toured all the villages and towns. He came back to his king and this is what he said to him:

“I saw a country where all the roads are well laid, and all the houses are neatly built and freshly painted white; I saw villages where all the cottages are well cared for, surrounded by little orchards filled with orange trees, apple trees, cherry trees and other trees and vegetables; I saw field after field sown with wheat and barley, broad beans and corn, stretching farther than the eye can see. And I saw at each dwelling one or two goats, some chickens, ducks and geese; I saw the prairies swarming with lambs; at evenfall, I saw herds of cows coming down the mountains. I saw smiling faces, and heard singing everywhere. And I did not meet a single beggar.”

The King began to pace up and down deep in thought; then he spoke to his High Chancellor.

“What you say is all well and good. But I will not be hoodwinked. The King of the Fatalists has always been a dunce. He never armed a single soldier in his life. How is he to defend all this if ever I were to get the urge to go and take it from him?”

“I saw,” the High Chancellor said in turn, “the river packed tight with ships, and I counted amongst them ten or so which were clad all over with iron. Crossing our borders, I saw a citadel on each rock and mountain top, with tremendous turrets. I saw soldiers everywhere I turned to look. I saw small children shooting with the bow, hunting deer and killing birds at the snap of one’s fingers!”

“What stuff and nonsense are you telling me?” interjected His Majesty. “You did not dream of these things, by any chance?”

“I saw them with my own eyes, my lord, I touched them with my hands.”

“How can this be, then? Did that beggarly cousin of mine stumble across some treasure? Tell me, what does his palace look like?”

“I walked by a mountain bursting with greenery, where, amongst the vegetation, the blossoming orange trees vied with the flowering almond trees for beauty, as lovely in their attire as brides on their wedding day. I went all the way up and was greatly astonished to find there a great half-ruined edifice, with a donjon tower, which alone seemed habitable. At the windows, I saw spotless white curtains, and all around the tower there were cows and goats grazing, keeping good company with the chickens. Passing under an open window, I heard sparkling female laughter. But I saw no one. I descended the mountain, and asked who lived in that ruin. And the people answered: ‘The King!’ I did not believe them, so I asked elsewhere. Again they

told me that it was the King’s palace. And again I did not believe them, and I went to the camp, which is by the river. There I saw many tents, but few soldiers, so I asked where the men were. They replied: ‘In the fields!’ And I asked who lived in the ruin on the summit of the mountain. And again they said: ‘The King!’ Seeing my bafflement, they indicated a youth who was just arriving, dressed in white woollen clothes, same as all the other soldiers, his arrows in a quiver slung behind his back, bow in hand. His face was covered with dust and dripping with sweat; around his waist he wore an old leather money belt, where a large dark stain could be seen. All the soldiers ran to him, and kissed his hands as soon as they saw him. And such was the joy that spread over their faces that I found myself bewildered, and I asked who it was. And they replied: ‘The Prince!’ Again, I did not believe them, and I laughed and asked them: ‘He wouldn’t also be living up there in the ruin on the mountain top, would he?’ And they answered: ‘No. That is where his father lives, the King. The Prince lives here with us.’ Then I left, my lord, and came back to tell you what I had seen and heard.”