A Tale Without a Name (17 page)

Read A Tale Without a Name Online

Authors: Penelope S. Delta

For a brief moment, the King the Royal Cousin remained speechless. Then very slowly, as though a great truth had been revealed to him, he said:

“Prudentius has risen from the grave!”

And he commanded that they bring to him from his treasuries a golden crown, bedecked with precious emeralds and diamonds, which his father had won as his

trophy in a great battle, after killing with his own hand the king who had worn it. He placed it in a beautifully wrought silver casket, sealed it, and handed it to the High Chancellor.

“Take with you immediately fifty of my best guardsmen and go with them to the Prince of the Fatalists, to whom you are to present this crown together with my swift-footed, snow-white mare; you are to ask him to accept the gifts I send him, the most precious possessions that I have in my treasuries, and to tell him that I seek his alliance and his friendship. Go now!”

I

N THE MEANTIME

, the King the Royal Uncle, after having toiled and struggled for three years, had managed to raise sufficient armed forces to relaunch his war campaign against his nephew, the King of the Fatalists.

He mounted his best steed, he belted on his great sword; his trumpeters were positioned at the forefront, proclaiming their progress through the land with a triumphant military march.

“Onwards, lads,” he cried out to his soldiers. “We shall stroll our way unopposed straight into the palace of the Regent himself.”

They walked for some few hours.

Gazing at the prairies across which he had retreated vanquished and dishonoured three years earlier, the King the Royal Uncle reckoned that this time, on his intended glorious return, he would be dragging behind him King Witless and the Prince, tied with ropes from the saddle of his horse. And he laughed a satanic laugh,

and rejoiced in advance at the shame and tears of his nephews.

“Oh! You shall pay so very dearly for that one victory of yours!” he grunted, menacing the open horizon with his fist.

All of a sudden, however, he stopped short, rubbed his eyes. Then he looked ahead once more, then to the right, after that to the left, pinched his arm hard to see whether he might mayhap be dreaming in his sleep, then rubbed his eyes hard a second time.

“But what has come over me, then?” he said uneasily. “Am I dreaming wide awake?”

He thundered:

“

General!

”

The General approached and bowed to the ground.

“Your Majesty?”

“Look ahead and tell me, what do you see?”

“A citadel, Your Majesty.”

“You are as blind as a mole! Summon the Major-General!” said the King crossly.

The Major-General came and bowed to the ground.

“Your Majesty?”

“Take a look around you, there, towards the border, and tell me, what can you see?”

“Citadels, Your Majesty.”

“You are an ass!” yelled the King the Royal Uncle wildly. “An ass and a traitor! Order the Centurion to come here at once, and vanish from my sight!”

The Centurion too came, and bowed to the ground.

“Can you make out that mountain over there?” the King the Royal Uncle asked curtly.

“Yes, Your Majesty.”

“What is that thing on top of it, a pile of rubble or something of that sort?”

“It is not rubble,” said the Centurion, shading his eyes with his hand, “it is a mighty citadel—”

He had no time to finish. With a sweep of his sword, the King the Royal Uncle had lopped off his head.

Then he turned to his soldiers and shouted to them, foaming with rage:

“What is perched up there, lads, will someone finally tell me?”

And the whole army in one voice cried out:

“A citadel, and farther down another citadel, and farther down another citadel; as far as the eye can see, citadels and more citadels!”

Then the King the Royal Uncle hung his head low on his chest and cried with blind fury.

He sent a reconnaissance party ahead, to see what all these citadels were like. But as soon as the scouts even tried to get nearer, a storm blast of arrows greeted them and drove them to mad flight.

They went farther away, everywhere was the same.

They attempted to pass between two citadels, and from both sides so many arrows flew out at them that half the soldiers were left dead on the spot.

As soon as the King the Royal Uncle saw that he could no longer get through, he bit his hands with such rage, and he filled up inside with so much yellow bile, that he was taken ill again and had to return to his palace.

He remained there for some days, brooding with spite, holed up in his rooms. Then he summoned his High Chancellor and said to him:

“Take immediately ten of the best soldiers in my personal guard, go to the kingdom of the Fatalists and tell the Prince to come to me at once, for I wish to give him in marriage the hand of the Princess, my royal daughter. Go now!”

The High Chancellor left with the ten bodyguards, and went to the kingdom of the Fatalists, where he requested to see the Prince.

They led him to a tent. Sitting on a wooden stool, before a roughly fashioned wooden table, a youth was reading some sheets of paper. From the corner of his eye, the High Chancellor saw with bewilderment that these sheets of paper bore the golden seal of the King the Royal Cousin.

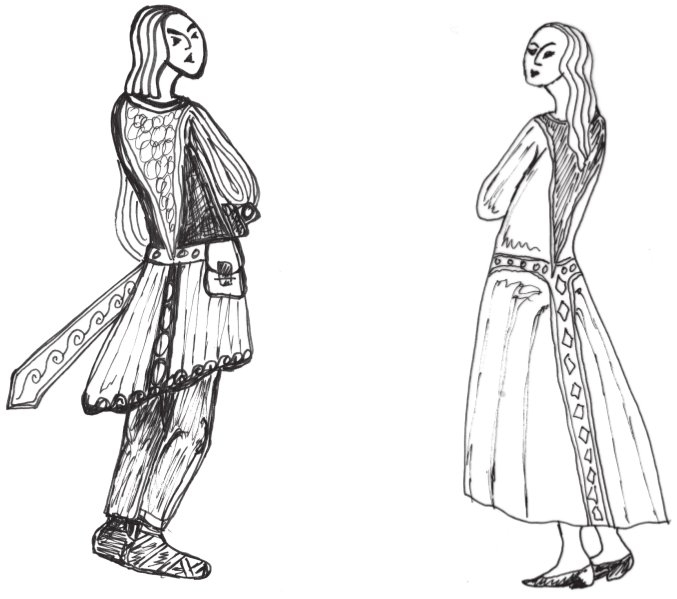

The youth wore white woollen clothes, and differed in nothing from the other soldiers who surrounded him, except for a shabby leather money belt that he wore around his waist; a black stain could be seen spreading across it.

And yet kneeling in front of this youth was an elderly nobleman, richly attired in gold-embroidered robes of velvet, holding a precious silver casket in his hands. With profound respect he was waiting for the youth to finish his reading so he could then present the casket to him.

The young man lifted up his head, and saw the envoy of the King the Royal Uncle.

“Who are you and what is your purpose?” he asked.

“I seek audience with the Prince, the son of the King of the Fatalists,” replied the High Chancellor.

“I am he,” said the Prince. “Now, state your business.”

For all that he was so very simply dressed, there was such nobility in his voice and in the way he carried himself that the envoy of the King the Royal Uncle fell on his knees.

“Your Royal Highness!” he said. “The King your Royal Uncle and my liege has commissioned me hither to bid you come to his kingdom at once, for he wants you to marry his daughter the Princess.”

The Prince’s eyes flashed, but he restrained himself.

“Tell your lord that I do not take orders from him. I shall not come as he bids. But I would not like you to leave empty-handed. Your master offered a gift once to my father, the King. Then we were not in a position to return his generosity in kind. But now I shall give you to take to your liege a gift worthy of the honour he conveys upon me by choosing me among all other men to be his son-in-law and husband of his daughter the Princess.”

He motioned to Polycarpus, who left that very instant, leapt on his horse, and galloping flew up to the palace, where he dismounted and rushed into the dining hall.

The King was playing a game of chess with Mistress Wise. Sitting by the window, Jealousia was singing and

turning her spinning wheel, while next to her, silent and smiling, Spitefulnia was stuffing a pillow.

Sunk in deep concentration, Knowledge and Little Irene were examining at the table the records of the cook’s expenses; Queen Barmy was knitting a woolly hat for the old King’s bald head.

Polycarpus dashed straight up to Little Irene.

“My Princess, the donkey’s head! The hour has come!” he cried, his voice faltering.

Nobody understood him.

“What hour? What are you talking about?” they all asked.

Little Irene alone understood. She stood up, blushing with delight.

“Has a message come from the King the Royal Uncle?” she asked.

“Yes, my Princess,” replied Polycarpus. “He is seeking to have the Prince as his son-in-law.”

“What’s that?” bellowed the King.

Knowledge had risen too, and asked nervously:

“What answer did the Prince give?”

“Here is his answer!” cried Little Irene happily.

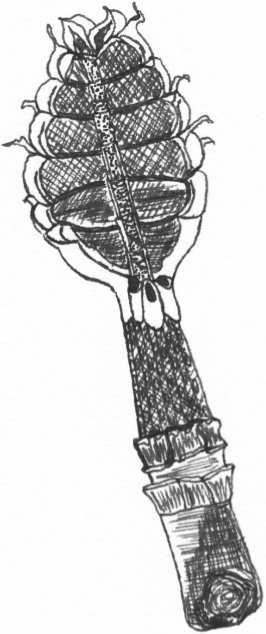

And climbing on a stool, she seized from above the gold-leaf cabinet the donkey’s head that hung there on a nail with its tin crown; she wrapped these in the red silk scarf that she had kept safely away in her drawer, and put everything in a basket. Then she sewed a sturdy piece of canvas over the top, and handed the basket to Polycarpus.

The equerry mounted his horse once more, and galloped down to the camp.

The Prince took the basket, and handed it to the envoy of the King the Royal Uncle.

“Take this,” he said, “and give it to your liege. Do not forget to repeat to him the words I said to you. Now go.”

And turning to the High Chancellor of the King the Royal Cousin, he said:

“Tell your lord that I thank him. Gifts my father the King cannot send him yet, for our kingdom is still poor, and we need all our florins. But our friendship he will indeed have, and joyfully we accept his offer of alliance, which does us honour. Godspeed to you.”

The two envoys bowed deeply, and each went on his way.

S

ILVER CASKET IN HAND

, the Prince leapt on the white mare, the gift of the King the Royal Cousin, and accompanied by Polycarpus he scaled the mountain all the way up to the palace.

The table was already set. They were waiting for the two of them before they might begin.

The Prince ran up to his father, knelt before him and handed him the silver casket.

“My father and my king,” he said with feeling, “I took away from you your crown one day, when the nation demanded sacrifices from each of us. Today the nation lifts up its head once more, it has become strong, and with its strength it now inspires the respect of its enemies. Take back your crown, my king and father, it is the nation’s gift to you.”

The King lifted up the lid, and, seeing the magnificent crown with its precious stones, he stood there stunned, his mouth agape.

“What is this? How came you by it?” he asked at last.

“It is the gift of the King our Royal Cousin, who asks for our friendship and desires an alliance with us,” replied the Prince.

The King then rose, took the crown from the casket, and placed it on his son’s head.

“You wear it, my son,” he said, visibly moved. “You deserve such a crown, because it is with your hard efforts and your strength that you have succeeded in earning it. A while ago now, I made you Regent and my equal. Now I am an old man, I am weary of hearing about matters that require my attention; I wish to spend my final years in peace. You take the crown, together with its heavy burdens, and rule now on your own the kingdom you have raised from the dead by force of will alone.”

The following day, the King convened all his people to the camp by the riverbank, and there announced to everyone that he was stepping down from his position as ruler of the State, and that he was surrendering the crown and the kingship to his son, the Prince.

With these words, he placed the precious crown on his son’s head, and anointed him King of the Fatalists.

From every breast, there sprang a great cry:

“Long live Prudentius II! Long live our King!”

The people’s joy knew no bounds. They all wanted to kiss the hands of the old King who had recognized the worth of his son, and of the new King, the saviour of their nation.

That day was proclaimed a holiday across the entire land.

When the new king, Prudentius II, went up to the palace with his new High Chancellor, Polycarpus, he found again all the family gathered in the dining hall.

He looked at the empty hook on the wall above the gold-leaf cabinet, and let a deep sigh escape from his lips.

“Now that that revolting donkey’s head is gone,” he said, “I can finally say that I feel free to undertake great things.”

And, turning to Knowledge, who was smiling at him, joyful and blushing pink:

“Would you like to help me, Knowledge?”

“I?” exclaimed the maiden, turning an even deeper hue of scarlet. “I? How could I be of help to you?”

“Be my wife and my queen,” said Prudentius. “You have done me so much good with your advice! Tell me, Knowledge, wouldn’t you like to help me govern this land?”

But before the maiden had time to reply, the old King had clasped both of them in his arms.

“With all my blessings,” he said, “

yes! Together

you shall rule the state.”

“And when the King our Royal Uncle finds out about your engagement, what will he say?” asked Little Irene, laughing gaily.

“He shall request your hand for his son,” said Mistress Wise. And with a wink made a sign to the King to look at Polycarpus.

The miserable High Chancellor had grown ashen upon hearing the words of Mistress Wise; trembling all over, he

too was looking at Little Irene, as though expecting to hear from her lips his own death sentence.

The Princess blushed a bright ruby red, turned and saw him; she lowered her eyes, shy and numb.

“And… would you accept that offer, my Princess?” asked the High Chancellor, his voice choking.

“No, Polycarpus…” murmured Little Irene, without looking at him.

“I do indeed hope that the King our Royal Uncle shall never extend to us such an offer,” said Prudentius, laughing mirthfully. “Or his anger will have reason to flare up again. For we very much desire Little Irene to remain here.”

And taking his sister’s hand, he placed it on the hand of Polycarpus, who almost lost his wits for joy.

“On the contrary! He should make the offer, so that he might receive a second serving of our contempt!” said the old King, who could still not put the donkey’s head out of his mind.

And happy, embracing his children, he added:

“And should the whimsy take him, just let him come back with his army and then he shall feel indeed how sharply Miserlix’s arrows can pierce.”

But the poor King the Royal Uncle never had a chance of receiving that second mighty serving of contempt, nor did he have occasion to test whether Miserlix’s arrows could pierce or not.

When he opened the basket and recognized the donkey’s head, and heard the Prince’s words as repeated to him by

his High Chancellor, such mad fury seized hold of him that he fell like a log on the floor.

And when they lifted him up to carry him to his bed, they saw that he was dead.

On the day of his coronation, Prudentius II went to the river to hold a memorial service in honour of all those who had fallen during that famous nocturnal battle.

Under the shade of the plane trees, two white crosses stood side by side: the grave of Polydorus and the grave of the youth from the tavern.

Prudentius placed a laurel wreath on each cross.

“Place a second wreath on this one, my lord,” said the master builder, indicating Polydorus’s grave.

“A second wreath? What do you mean?”

“In honour of the Unrevealed Hero,” replied the master builder.

Prudentius cast him a hard look.

“I do not understand,” he said.

“The one-armed man never made it back from his last crossing,” my lord.

“What became of him, do you know? Have you had any news?” asked Prudentius.

The master builder slowly shook his head.

“For three years now I have waited for him,” he said, “and every nightfall, once the sun has set, I have come back to this same place, in the hope that perhaps he would return. But now I no longer expect him to come back…”

“He may have gone abroad, like so many others,” said Prudentius.

The master builder considered this carefully.

“I know that he did not,” he said at last. “As I knew him, he was a man who would have given up his life without many words, silent and unrevealed, for the sake of his country. Abandon his homeland during a time of danger? That he would never have done!”

For a good while neither of the two spoke.

Then the new King cut a laurel branch from the tree and laid it on Polydorus’s grave.

“To the Unrevealed Hero…” he said.

“And to all those who give up their lives in silence and with humility for the sake of their country, without their homeland ever coming to know who they were…” added the master builder.

And kneeling, they both paid their homage before the grave.

THE END