A Train in Winter (29 page)

Authors: Caroline Moorehead

It was in this version of hell that the 230 French women, some of them in their late fifties or early sixties, others still schoolgirls, accustomed to having enough to eat, warm beds to sleep in, clean clothes and the civility and decency of strangers, now found themselves.

Marching raggedly in their rows of five, keeping pace as best they could, clinging on to their few possessions, Charlotte in the fur hat given to her by Louis Jouvet, Mme van der Lee in her otter coat, the women were directed towards a building just inside the perimeter of the camp. What they saw, stretching in orderly lines over an immense white snowy field, were barracks, single-storey structures made of wood or stone, somewhat like stables with small windows. There was a corpse lying in their path. Too shocked to take much in, they jostled against each other and stepped over it.

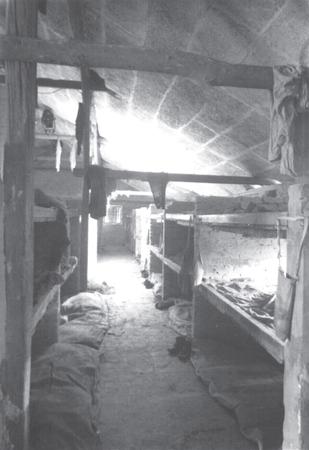

There was no heat in the barracks into which they were led, but, after their agonisingly cold, faltering, slithering walk, they were pleased to sit down, even if all they could find to sit on were the edges of stone and wooden slatted bunks that rose in tiers to the ceiling. At midday, two prisoners in striped clothes arrived with a cauldron of hot liquid, a thin gruel-like soup made of grasses, and red enamel bowls were handed out. Not everyone drank the soup, saying that the bowls had a fetid, sickening smell, and that they would prefer to wait for the bread. There was no bread, they were told, and they would do better to eat whatever came their way. It was only later that they learnt that the smell that stuck to the bowls came from the fact that the women in the barracks, suffering from dysentery, could not always reach the latrines in the night and used the bowls instead. As the French women hesitated, the Germans and the Poles who were already in the barracks when they arrived pressed forwards, fighting each other to get at the soup.

Inside one of the women’s barracks

After this, the doors to the barracks opened and a group of SS men entered. One stepped forward and asked whether there was a dentist among the French women, the camp dentist having recently died. Danielle put her hand up and was led out.

Now began the process of induction into the life of Birkenau. The women’s names were called out, with Marie-Claude acting as interpreter. They were told to undress, put their clothes and all their other belongings, including any photographs of their families, into their cases and mark these with their names. By some sleight of hand, Charlotte managed to hold on to her watch. Forced to hand over her photograph of Claude, Annette Epaud found a way of hiding the little drawing of him.

They were led into a room where other prisoners were waiting with scissors to cut their hair, getting as close to the scalp as possible. Their pubic hair was also clipped while another woman wiped the shorn and bald parts with a rag dipped in petrol as a disinfectant. ‘Look,’ said Josée Alonso, who went first and whose good humour had done so much to cheer them up in Romainville, ‘you will all be able to look just as elegant as me.’ When it came to the turn of 18-year-old Hélène Brabander, whose doctor father François and brother Romuald had been unloaded from the train at Sachsenhausen, her mother Sophie took the scissors and cut her daughter’s hair herself. Janine Herschel, one of the very few Jews on the train—though, having used a false certificate of baptism, no one knew that she was Jewish—offered an SS guard her gold watch, studded with diamonds, in return for sparing her bleached, blond hair. The SS man took the watch and Janine’s hair was chopped off anyway.

As there was not enough water for a shower, they were next led, naked, into a room full of steam. Some of the women had never taken their clothes off in front of strangers before. They shrank back as SS guards, men and women, came in and laughed at their naked bodies. Simone, looking around desperately for a face she recognised among the bald heads, heard Cécile call out: ‘Come here, come and sit with us.

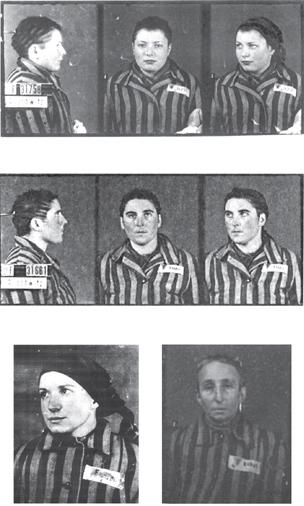

Women prisoners in Birkenau, soon after arrival

After this came the tattoo, a series of pricks, each woman’s number taken from the transport on which she reached the camp—theirs was the transport of the 31000—traced on the inside of their lower left arm by a French Jewish prisoner, who assured them that it would not hurt. They felt that they were being branded, like cattle. Charlotte became number 31,661, Cécile 31,650, Betty 31,668. The 230 women, for ever after, would be known as

Le Convoi des 31000

.

Next, still naked, they were led into yet another room, this one full of what looked like rags piled up on the floor, where other prisoners were waiting to issue each woman with a sleeveless vest, a pair of grey knickers reaching to the knees, a scarf, a dress, a jacket and rough grey socks and stockings without elastic. The outer garments were all made of the same striped material. They took what they were given, regardless of size, the large women crammed into small dresses, the small enveloped in sacklike jackets. Worse, the clothes were filthy, spotted with blood and pus and faeces, and damp from some rudimentary attempts at disinfection. When Simone’s turn came to get shoes, all that were left were clogs, with a band of material roughly nailed over the top, which meant that her toes and heels were bare. It made walking hard. Mado got slippers of torn felt.

Their last task was to sew on to each jacket and dress their personal numbers, as well as an F, for French, and a red triangle. Asking what this meant, they were told that it denoted their status as political prisoners, those held for ‘anti-German activities’, and that they would do well to learn the meaning of the other symbols: green for the criminal prisoners, purple for the Jehovah’s Witnesses, black for the ‘asocials’, pink for homosexuals, a six-pointed Star of David for the Jews. Some prisoners wore a combination of symbols—as Jews, ‘race defilers’, recidivists and criminals.

The women discovered that they were regarded as ‘dangerous’, and that the other prisoners had been ordered to turn their backs as they passed by. A Dutch woman in the sewing room asked: ‘How many are you?’ Told that there were 230 of them, she said: ‘In a month, there will only be thirty of you.’ She herself, she added, had been one of a thousand women arriving on a train from Holland in October: now she was the only one left alive. Had the others been executed? No, she replied, they died after the roll calls, hours and hours standing still in the snow and ice. It was easier, more comforting, not to believe her. When the French women left to return to the barracks, the icy cold froze their damp clothes stiff.

Simone, Charlotte, Betty and Emma, taken soon after arriving in Birkenau

Block 14, where the women were taken, to their immense relief all together, was a quarantine block; it was here that they were to spend the first fortnight in Birkenau, though one morning they were marched off to the men’s camp, to be photographed and measured. Spared the work details that would later take them to the factories, brickyards and marshes, they were not let off the roll calls; all too soon, they understood the Dutch woman’s warning. At 3.30 in the morning, long before it grew light, every woman in the camp was harried out of her bunk and barracks by

kapos

with whips, to stand in the gluey mud and snow to await the arrival of the SS to count them.

From the first, the French women clung together, in groups, each slipping her hands under the arms of the woman in front, the rows constantly changing place so that no one spent too long on the outside. ‘We held on to each other,’ Madeleine Dissoubray would later say. ‘If someone was particularly cold, we just kept them in the middle.’ Using Charlotte’s watch, they decided that they would swap places every fifteen minutes. To deal with the extreme cold, Charlotte tried to pretend she was somewhere else, to recite poems to herself in order ‘to remain me’, but the reality of the cold and exhaustion was too overwhelming. One of the women was having trouble standing up, and a guard hit her. Adelaïde went over to help her and was hit herself. The French women felt terrified and confused.

With the dawn, the count began. When the numbers did not tally, the counting started again. The rows had to be neat, the squares of women perfectly formed up. The guards shouted, shoved, dealt out blows; the dogs growled and snapped. Roll calls could last several hours; they were repeated at the end of each day. It was impossible to clean off the mud and excrement that clung to the women’s feet, and mud haunted their dreams. Lulu kept thinking of the mud and trenches of the First World War, and of her father at Verdun. To fall during roll call could mean death, for there was no way to clean or change and the wet muddy clothes froze on their backs. To lose shoes could also bring death, for there were no others. Women spotted barefoot were often sent straight to the gas chambers, women being easier to replace than shoes. Every dawn, Charlotte wondered whether she would survive another day. One morning she fainted, but was caught and slapped by Viva to bring her round.

Even as the French women reached Birkenau, it was clear that not all would, or could, or would choose, to survive. A look of death became imprinted on some of their faces. There was something too degrading, too shocking for some of the women to bear. Using the latrines meant wading through excrement and crouching over a long open sewer, trying not to fall in. Accustomed to order and predictability, they had neither the strength nor the desire to adjust to a world whose rules seemed so arbitrary and so barbaric.

The first to die were the older women, but precisely what they died of would be hard to say, other than of shock. Marie Gabb, who was 53 and had belonged to the Resistance networks around Tours, died on the first day in Birkenau, even before the roll call. Soon after, at the second roll call, Léona Bouillard slipped to the ground; when her neighbours tried to lift her up, they found that she was dead. Léona was 57 and came from the Ardennes and she had become popular among the younger women for her kind ways; they thought of her as their grandmother and called her Nanna Bouillard. Four of the others carried her body back to the barracks.

After her came 50-year-old Léa Lambert, who had sheltered prisoners escaping from Germany. Then Suzanne Costentin, a schoolteacher friend of Madeleine’s and Germaine’s, arrested for writing a tract about the men shot as hostages, who was beaten by a guard so badly that her body was bruised all over. Suzanne died when her fingers and toes became so frozen with frostbite and gangrene that she could no longer climb on to her bunk. Yvonne Cavé, whose parents ran a mushroom farm and whose only crime seems to have been that she had cursed a young Frenchman, preening in his new uniform as a German volunteer, died because her shoes were stolen in the night. Forced to go barefoot to the morning roll call, which was particularly long that day, she got frostbite in her feet. All day her legs became more and more swollen; she died, as dusk was falling.

Neither Antoine Bibault, nor Jeanne Hervé, nor Lucienne Ferre—the three suspected

délatrices

, believed to have informed on the Resistance—survived for long. Ostracised by the group, they rapidly became defenceless. Many years later, asked why they died so quickly, Cécile would only say: ‘They died. That’s all.’ Knowing that she did not have long to live, Lucienne said to Hélène Bolleau: ‘Well, I only got what I deserved.’ She was 21.