A Trip to the Beach (17 page)

Chapter 10

Marcus lived with his uncle Julius, a fisherman from West End whose lackadaisical lifestyle served as a sharp contrast to the atmosphere at Blanchard's. Because he was the only member of our staff who worked in the morning, Marcus wasn't as much a part of the Blanchard family as the others. Bob and I liked him, though, and felt something of a parental responsibility toward him in spite of his less-than-perfect performance as an employee. He walked with a playful bounce in his step and always seemed to be smiling. No job was too menial for Marcus, and in fact he often volunteered to do additional mopping or scrubbing when he saw the need. His enthusiasm made up for the broken equipment and his lateness.

On more than one occasion we stopped by the restaurant while Marcus was still cleaning up and found several of his friends in the kitchen watching him work. We felt a little uncomfortable about our kitchen being used as a gathering place and asked Marcus to meet his friends when he was done.

“I ain' got no trans,” Marcus said. “They jus' here to give me a liff.”

There is a code of silence that exists in every workplace when it comes to turning in another employee, but in Anguilla, telling the boss that a co-worker is doing something wrong is almost a violation of national honor. Informants can be permanently ostracized. So when one of our staff came to us to talk about Marcus, we recognized the risk he was taking.

He arrived at our house early one Sunday morning and made us promise not to tell Marcusâor anyone elseâthat he had come. After Bob and I solemnly swore ourselves to secrecy, he took a deep breath and blurted out his news.

“Marcus dealin' drugs from the kitchen.” He paused, waiting for a reaction, but we were dumbfounded. “You gotta get ridda he,” we were cautioned. “He a bad dude, an' if the police catches him dealin' drugs at Blanchard's, you in trouble too. One a he friends a big dealer. Marcus work for he.”

“Damn that Marcus,” Bob said. “I can't believe he would do this to us. Do you think the rest of the staff knows about this?”

“Everybody know 'cept you.” He looked at us apologetically, as if he had just insulted us. “He gonna bring the whole place down if you ain' get ridda he.”

“Look,” I said. “First of all, I want to tell you how grateful we are that you came here to tell us about Marcus. I know how difficult it must have been for you to make that decision, and it means so much to us that you did.”

“You's good people, and Blanchard's is too important to the rest of we. I had to say somethin'.”

“We'll let him go tomorrow morning, and we will not mention your name to anyone,” I promised.

“Poor Marcus,” Bob said.

“Poor Marcus, nuttin'.” Our informant was disgusted. “He a bad dude.” With that he got up to leave, and as we thanked him again for coming forward, he repeated, “Marcus a bad dude.”

He drove away, and I immediately said, “Bob, we have to get some advice on how to handle this. I know we have to let him go, but what if we fire him and he complains to the labor department? We don't really have any proof, and we could end up in big trouble. I think we should call Bennie and see what he thinks.”

“Oh, God, I hadn't thought of that. Just what we need. We try to fire a drug dealer, and the labor department comes down on us because we can't prove it.”

I caught Bennie at home just as he was leaving for church. He knew I wouldn't be calling on Sunday morning unless it was important, so he insisted I give him a full report. “It's very easy,” Bennie said when I finished, relishing his role as our advisor. “You do have to fire the boy, but you must notify the labor department before he has a chance to go in and make a formal complaint. Write a letter to him explaining why you are letting him go. Tell him you cannot tolerate any chance of drug activity at your place of business, and therefore you are not giving him the usual required notice. Send a copy to the labor department, asking them to keep it on file. That's all you need to do to protect yourself.”

Relieved, I thanked Bennie and wrote the letter. The next morning we waited for Marcus to arrive at the restaurant. I felt as if I were about to kick my own son out of the house, yet I knew he had to go. I kept repeating our employee's words to bolster my courage: “He'll bring the whole place down.” There was no question that if the police found any drug activity at Blanchard's, we would be blamed. It was also a little scary not knowing how deeply Marcus was involved. Firing a drug dealer could have further ramifications. What if Marcus decided to get even? His unsavory friends could be dangerous.

At ten-thirty, Marcus wandered in with his usual bounce and a cheery “Good morning.”

I looked at Bob, knowing I couldn't say the words. “Marcus,” Bob said, “we're going to have to let you go. You've been dealing drugs from here, and we can't allow that.”

Marcus's expression told me he was shocked that we had found out. He knew how much we cared about him, and tried to defend himself. “I ain' been dealin' no drugs.”

“Yes, you have,” Bob continued.

I felt like crying. Marcus looked like a scared little boy, and I wanted to hug him and tell him we were there to help. I knew that was impossible, though. Not in Anguilla. Our work permits could be canceled at any time, and we just couldn't risk getting involved.

“We also know one of your friends is a big-time dealer,” Bob said.

Marcus dropped his head and said, “Please, Bob, I wan' this job.”

“I'm sorry,” Bob answered, “but you've jeopardized the whole restaurant, and we have no choice. I just want to say a couple of things, and I want you to listen very carefully.” Bob spoke slowly, choosing his words cautiously. “Melinda and I both care about you, Marcus, and we feel very bad about this. I think you are headed down the wrong road, and someday you will get caught.” He paused, either to let that sink in or to figure out what to say next. “I know you go to St. Martin a lot, Marcus, and if you get caught over there, you'll end up in the underground prison in Guadeloupe. That's where they send drug dealers; you'll never see daylight again. Do you understand that?”

I handed Marcus the letter of termination as a formality. I knew he couldn't read it, but Bennie said it was important.

“You ain' gonna turn me in, are you?” Marcus asked.

“No,” Bob said, “but I want you to think about what I've said, okay?”

And with that, Marcus turned and walked down the road. I could still remember him mimicking and laughing at the cartoon characters in the Thanksgiving Day parade. He was just a child.

It was two weeks before the local election and our kitchen buzzed with political banter. Every five years each of the seven districts on the island voted for their representative to the House of Assembly. England provides Anguilla with a British governor, but from what I gathered from the political debates among Blanchard's staff, locally elected officials are the ones who really have the power.

Campaigns here are simple. There are no investigations into past indiscretions and no rules about divesting oneself of conflicting interests. Politics in such a small community understandably revolves around people more than issues. Constituents vote for the people they are closest to, the people they trust. And with only a handful of surnames dominating the phone book, many times the vote goes to a family member. This is not to say elections are unfair or even predictable; like anywhere else in the world, voters select officials they feel will make the right decisions. It's just that in tiny Anguilla, the choices are closer to home.

After the election, the new members of the House of Assembly decide who is most qualified to fill the various positions within the local government. They appoint a chief minister, a minister of finance, a minister of public works, a minister of education, and others. The governor, sent by Her Majesty the queen, works in conjunction with the local officials and shares in running the government.

Night after night, kitchen cleanup was completed in record time so that our staff could get to a political rally. Ozzie was the smallest of our crew, but when it came to politics, his presence filled the room. “Mel, Eddie talkin' tonight,” he said animatedly. “He the first man who get school bus to go Sandy Ground, ya know. Eddie Baird, he the man.” Ozzie's usual dance routines turned into brilliant impersonations of the various candidates. He strode around the kitchen, chest puffed up and feet turned out, mimicking the opposition.

“Yeah,” Bug would argue. “But David the man who gonna keep Anguilla goin' the right direction. He the man we need. He think bigger than school buses.”

“You ain' got children in Sandy Ground,” Ozzie retorted. “We ain' wan' our kids walkin' up that long hill to go school.”

Blanchard's kitchen reflected the political divisions of Anguilla, albeit in the friendliest of fashions. Bug cheerfully disagreed with Ozzie and Garrilin with Lowell. They all cared deeply about the future of Anguilla, and their passion was sometimes deafening. As with so many kitchen discussions, I had to remind them we had customers just around the corner.

Posters were stapled to telephone poles, flyers were distributed at local shops, and billboards on elaborate wooden stands were erected along the main road. Nobody was making campaign buttons, but I thought it would have been a good business to start. Everyone seemed to wear a T-shirt promoting his or her preferred candidate, and the local radio station continually broadcasted political speeches and commentaries.

Politics permeated every facet of local life, yet our staff knew better than to lobby Bob and me. We listened to the debates but said not a word. We had friends representing all parties in the race and wanted to keep them as friends.

At six o'clock on the night before the elections Blanchard's was busy with its usual predinner activities. The dining room was being set, Shabby was filleting fish, and Garrilin was washing greens for salad. I went into the walk-in cooler to take a quick inventory, and by the time I came out, everyone was gone. Ozzie had deserted his station; Bug's sink was filled with suds and ready to go, but there was no Bug. I ran to the dining room and found it empty as well. Just as I was starting to get nervous that I'd missed some emergency, Bob came into the bar, motioning for me to come outside.

There they all were in the parking area, a jumble of excitement. “What's going on?” I asked Miguel.

“Motorcade” was all he said.

“Mel,” Lowell explained, “this a motorcade for the opposition. These the people who

ain'

in power and who

wanna

be in power.”

“But I don't see any cars,” I said.

“They comin',” Ozzie said. “They jus' pass though South Hill and they comin' Meads Bay now.” How he knew their exact location, I hadn't a clue. But as our entire clan stood by the road I could feel the tension mount, and in a few minutes I heard horns tooting in the distance. As the cars rounded the corner by the salt pond, our staff burst into loud cheers and jeers, depending on whose side they were on.

I don't know how many vehicles were in the motorcade, but it went on for miles and miles down the road. Hundreds of people were piled into the back of pickups, dump trucks, and jeeps; even a backhoe had a slew of hangers-on. By the time they were directly in front of Blanchard's, the chorus of tooting horns was blaring. I saw dozens of familiar faces, and everyone waved frantically as they passed.

Fifteen minutes later the horns were fading in the distance, and we all filed back into the restaurant to prepare for dinner. We were behind schedule and had to work extra fast to make up for lost time.

A few minutes later Garrilin looked at me and grinned. “Here we go again.” Before I knew it, the entire gang was back outside. I followed, knowing there was no hope of getting anyone to focus on dinner with motorcade number two now approaching.

“This the other side now,” Lowell said. “These be the people

in

power and they wanna

stay

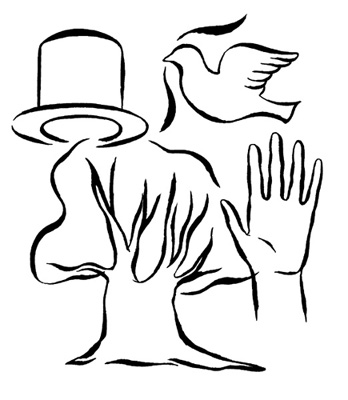

in power.” Each party had a symbol that they used for the campaign: the hand, the clock, the bird, and the tree. This motorcade clearly had a large contingent from the tree party, because people were energetically waving huge branches out of car windows and trucks.

The motorcade was almost past when our first guests arrived for dinner. We weren't quite ready and explained about the big day coming up. Bob bought them a glass of wine and stalled them with a few stories. It was an exhilarating evening in the kitchen. The polls would open the next morning at seven, and everyone was fired up and ready for the count.

The voting took place in schools and under tents in each district around the island. People lined up to make their mark and drop their paper into the ballot box. A candidate can sometimes win by only a few votes, so the count was done carefully and in public, to avoid any mistakes. On election night everyone showed up early for work. They couldn't bear the thought of being apart when the results started coming in. The TV in the kitchen was tuned to the local station, where the counting of the ballots was being televised, and Ozzie's car radio was tuned to Radio Anguilla as it reported the tally. Bug and Ozzie took turns running to the parking lot to hear the latest commentary.