A World Lit Only by Fire (22 page)

Read A World Lit Only by Fire Online

Authors: William Manchester

E

VEN AFTER

it had become obvious that medieval Christianity and the reawakened reason of the ancient world were on a collision course,

the clash was not abrupt. Critics of the new intellectualism approached the issue cautiously, beginning, in an early reference

to it, with a straightforward (if restrictive)definition: “The Humanist, I meane him that affects the knowledge of State affairs,

Histories, [et cetera].” True believers began to draw a distinction—it was to be observed for more than a century—between

“secular writers” (humanists) and “divines,” or “devines” (themselves). Then a scholar was singled out for oblique censure:

“I might repute him as a good humanist, but not a good devine.”

By then the divines were ready to fight, and the first quarrel they opened—over higher education—was one the humanists,

it seemed, could hardly ignore. Proper university instruction, wrote one cleric, should consist in “deliuering a direct order

of construction for the releefe of weake Grammacists, not in tempting by curious deuise and disposition to conte [content]

courtly Humanists.” But the flung gauntlet was ignored. Another divine described the spectrum of learning as arching from

“the strictest Roman Catholicism,” representing perfection, to “the nakedest humanism.” This too provoked no response. An

abusive reference to “heathen-minded Humanists” was followed by another, to “their system—usually called

Humanism

,” which, the writer explained, sought “to level all family distinctions, all differences of rank, all nationality, all positive

moral obligations, all positive religion, and to train all mankind to be as … the highest accomplishment.” These were absurd

charges, easily refuted, but no learned scholar bothered to do it, and the divines, never an intellectual match for those

they sought to draw, were reduced to limning the plight of a man bereft of his soul: “With the accession of humanistic ideas,

he had lost all belief in the Christian religion.”

Although the issue was profound, discussion of it remained a monologue. The humanists were hardly inarticulate; they were

merely reserving their concern for immediate issues, such as the gross abuse of authority in the ecclesiastical hierarchy.

Here the divines tried to intervene as amicus curiae. One asked sarcastically: “What a Discovery is it … that Vice raged at

Court? Is it but the Hackney Observation of all Humanists?” In a sense it was exactly that; eminent spokesmen for humanism

were discovering vice in parishes, dioceses, monastic orders, and, above all, in the Holy See, and if they sounded hackneyed

it was because repetition is unavoidable when the same offenses turn up again and again.

Reflective men make uncomfortable prosecutors. By nature and by training, they tend to see the other side and give it equal

weight. Clerical misconduct aroused the anger of some humanists, but others, bred to be devout, found the matter disturbing.

They searched for compromises, envying painters and sculptors who could overlook the goings-on in Rome. Not all artists did,

however. The shrewdest of them, aware that the papacy was spending fortunes on Vatican art even as famine stalked Europe,

suspected the Vatican of exploiting them, tightening its grip on the masses by overawing them with beauty. One surprise rebel

was Michelangelo, in his role as coarchitect for the new St. Peter’s. Pope Leo ordered exquisite Tuscan marble from the remote

Pietrasanta range. The artist balked. Bringing it out, he said, would be too expensive. Unaware of Michelangelo’s mutiny,

but thinking along the same lines, Martin Luther objected to the vast sums being raised for reconstruction of the great cathedral’s

basilica. Luther was a man of faith, not reason. Nevertheless Leo’s prodigality troubled him. If the pope could see the poverty

of the German people, he wrote, “he would rather see St. Peter’s lying in ashes than that it should be built out of the blood

and hide of his sheep.”

Michelangelo had a choice. Luther’s conscience denied him one. That was also true of other troubled clerics, scholars, writers,

and philosophers. They

had

to speak out. Change was imperative. Only the informed and the literate could demand it, and in the Europe of that time,

they were few. At the outset, their objective was rehabilitation of the system, but this revolution, like Saturn—like all

revolutions—was destined to eat its own children.

To them this was tragic. The doctrine that the Church was perfect, that the very idea of change was heretical, deeply disturbed

learned Catholics, leaving them torn between faith and reason. In the eyes of Rome, Copernicus had died an apostate who had

tried to subvert Ptolemaic theory, endorsed by the Church in the second century, more than two hundred popes earlier. But

the solar system would not go away. It was too enormous. Within a century

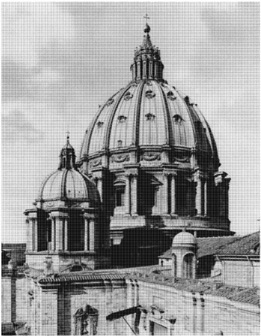

Michelangelo’s cupola of St. Peter’s, seen from the rear

Galileo Galilei of Florence would confirm the Copernican system. Summoned to Rome, he, too, was found guilty of heresy. When

he persisted in publishing his findings, he was called before the Inquisition, where, in 1633, under threat of torture, he

disavowed his belief in a revolving earth. As he left the tribunal, however, he was heard to mutter, “

Epur si muove

” (“And yet it does move”). His recantation therefore was judged inadequate. He died blind and in disgrace. More than two

centuries later, Thomas Henry Huxley, eulogizing him, scorned the Church as “the one great spiritual organization which is

able to resist, and must, as a matter of life and death, resist, the progress of science and modern civilization.”

But there had been little science and no modern civilization in the Dark Ages, when acceptance of papal supremacy by all Christendom

had rescued a continent from chaos. Faith had literally held Europe together then, giving hope to men who had been without

it. The most callous despots of the time, fearing God’s wrath, had yielded to papal commands, permitting the Church to intervene

when princes had been devouring one another, forcing them to submit to the argument that temporal rulers must yield to the

one authority whose sacraments promised eternal salvation. Eminent Catholics knew that. And their piety was central to their

personal lives. Now, though torn by inner conflict, they would shred “the seamless robe of Christ.” Jesus, commanding Peter

to build his Church, had predicted that “the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.” The gates of hell hadn’t; instead

the terrible task of destroying the inviolability of the one true faith fell upon the devout, who prayed that they be spared

it, and whose prayers were to be unanswered.

E

RASMUS, THE SON

of a priest, was a fastidious insomniac who spent much of his life in monasteries. Throughout the coming turmoil he remained

an orthodox Catholic, never losing his love of Christ, the Gospels, and rites that comforted the masses. In his

Colloquia familiaria

he wrote: “If anything is in common use with Christians that is not repugnant to the Holy Scriptures, I observe it for this

reason, that I may not offend other people.” Public controversy seemed to him an affront; though his doubts about clerical

abuses were profound, he kept them to himself until he was well into his forties. “Piety,” he wrote in a private letter, “requires

that we should sometimes conceal truth, that we should take care not to show it always, as if it did not matter when, where,

or to whom we show it. … Perhaps we must admit with Plato that lies are useful to the people.”

These were reassuring words in the College of Cardinals, where, in 1509, Erasmus, then in his early forties, was a guest.

His hosts yearned for serenity; they were weary of the bellicose Pope Julius II, who was forever invading this or that nearby

duchy, on one pretext or another, and they had become troubled by the increase in indiscretions of humanists who were more

aggressive and more outspoken than Erasmus. Among the first to arouse the Vatican’s displeasure had been Giovanni Pico della

Mirandola, whose father, the ruler of a minor Italian principality, had hired tutors to give his precocious son a thorough

humanist education.

The mature Pico developed a gift for combining the best elements from other philosophies with his own work, and his scholarship

had been widely admired until he argued that the Hebrew Cabalistic doctrine, an esoteric Jewish mysticism, supported Christian

theology. Greek and Latin scholarship were fashionable in Rome; but the suggestion of an affinity between Jewish thought and

the Gospels was unwelcome. Pico drew up nine hundred theological, ethical, mathematical, and philosophical theses which Christianity

had drawn from Hebrew, Arabic, Greek, and Latin sources and, in 1486, proposing to defend his position against any opponent,

invited humanists from all over the continent to Rome to debate them. No one arrived. They weren’t allowed to enter the city.

The pope had intervened. A papal commission denounced over a dozen of Pico’s theses as heretical, and he was ordered to publish

an

Apologia

regretting his forbidden thoughts. Even after he had complied, he was warned of further trouble. Fleeing to France, he was

arrested, briefly imprisoned, and, on his release—another sign of the age—was poisoned by his secretary.

Pico’s ordeal had been followed by the even more awkward Reuchlin affair. Johannes Reuchlin, a Bavarian humanist, had become

fluent in Hebrew and taught it to his Tübingen students.

Then, in 1509, Johannes Pfefferkorn, a Dominican monk who was also a converted rabbi, published

Judenspiegel

(

Mirror of the Jews

), an anti-Semitic book proposing that all works in Hebrew, including the Talmud, be burned. Reuchlin, dismayed by the possibility

of such desecration, formally protested to the emperor. Jewish scholarship should not be suppressed, he argued. Rather, two

chairs in Hebrew should be established at every German university. Pfefferkorn, he wrote, was an anti-intellectual “ass.”

Furious, the rabbi who had become a monk struck back with

Handspiegel

(

Hand Mirror

), accusing Reuchlin of being on the payroll of the Jews. Reuchlin’s riposte,

Augenspiegel

(

Eyeglass

), so outraged the Dominicans that the order, supported by the obscurantist clergy throughout Europe, lodged a charge of heresy

against him with the tribunal of the Inquisition in Cologne. The controversy raged for six years. Five universities in France

and Germany burned Reuchlin’s books, but in the end he was triumphant. Erasmus and Ulrich von Hutten, Maximilian’s new poet

laureate, were among those who rallied to his side. An episcopal court acquitted him, Pfefferkorn’s fire was canceled, and

the teaching of Hebrew spread, using Reuchlin’s grammar,

Rudimentia Hebraica

, as the universities’ basic text.

Because Erasmus was in Rome when this dispute broke out, his opinion was solicited. His mild reply—that he believed the

issue could be solved by quiet compromise—endeared him to his hosts. They first urged him to prolong his stay, then offered

him an ecclesiastical sinecure, suggesting that he settle among them permanently. Because of his eminence he had been courted

in every other European capital. This seemed the ultimate opportunity, however, and he was at the point of accepting it when

word arrived that the king of England had just died. Erasmus had known the new monarch, Henry VIII, since Henry’s boyhood.

Both were ardent Catholics, and while he was debating his future a personal letter from Henry reached him, proposing that

“you abandon all thought of settling elsewhere. Come to England, and assure yourself of a hearty welcome. You shall name your

own terms; they shall be as liberal and honourable as you please.”

That decided Erasmus; he packed his bags. The offer was irresistible—for private reasons. In Rome, even if he became a cardinal,

his manuscripts would be carefully scrutinized for possible heresy, but in England he would be free, protected by a powerful

sovereign. This was important because there were certain unorthodox reflections Erasmus wanted to put on paper and then publish.

Had his hosts at the Vatican known of them, it is likely that he would never have left the city. Given the morality of the

time, it is even possible that his body, like so many thousands before it, would have been washed up by the waters of the

Tiber.