A World Lit Only by Fire (23 page)

Read A World Lit Only by Fire Online

Authors: William Manchester

I

N REASONING

that truth must sometimes be concealed in the name of piety, Erasmus had been completely sincere. He had, in fact, done exactly

that with the sacred college. Safe in England, he intended to attack the entire Catholic superstructure. But he was no hypocrite.

Nor, by his lights, was he guilty of treachery; betrayal as we know it was so common in that age that it carried few moral

implications and aroused little resentment, even among sovereigns, prelates, and the learned. Furthermore, he was moved by

a higher loyalty. He had always assigned absolute priority to principles and was baffled by those who didn’t. “We must not

look to Erasmus for any realistic conception of human nature,” writes an intellectual historian. Brilliant, an accomplished

linguist, familiar with all the capitals of Europe, he was nevertheless ignorant of, and indifferent to, the secular world.

He never pondered, for example, the dilemma which was troubling Machiavelli in these years: whether a government can remain

in power if it practices the morality it preaches to its people. Nor had he ever coped with the vulgar tensions of everyday

life—sexual tension (he was a celibate), for example, or the need to earn a living. Others had always handled money matters

for him. It was no different in England. On his arrival there, the bishop of Rochester endowed him with $1,300 a year, a Kentish

parish awarded him its annual revenues, and friends and admirers provided him with cash gifts. He was spared any concern about

lodgings by Sir Thomas More, who, taking him into his own home, provided him with a servant. Erasmus scarcely noticed. He

said: “My home is where I have my library.”

His, in short, was the peculiar naïveté of the isolated intellectual. As an ecclesiastic, he had an encyclopedic knowledge

of clerical scandals, including the corruption in Rome. Other humanists had withdrawn from this squalor and found solace in

the Scriptures. Not Erasmus; by force of reason, he believed, he could resolve the abuses of Catholicism and keep Christendom

intact.

He miscalculated. Because the press as we know it had not even reached an embryonic stage, his knowledge of the world around

him, like that of his contemporaries, was confined to what he saw, heard, was told, or read in letters or conversation. And

because those around him were all members of the learned elite, he had no grasp of what the masses, the middle class, or most

of the nobility knew and thought. His appeal was to his peers. Once he took his stand, they would find him immensely persuasive.

But since his message would be incomprehensible to the lower clergy, where it counted, his appeals for reform would be impotent,

his triumph literally academic.

Had that been the sum of it, he would have been unheard. But he was a man of many gifts, and one of them altered history.

He possessed the extraordinary talent of making men laugh at the outrageous. Medieval men had known laughter—it is hard

to see how they could have got through the day without it—but their expression of merriment had been the guffaw, mirth for

its own sake; as Rabelais had written in his prologue to

Gargantua

, that kind of laughter is almost a man’s birthright (“

Pour ce que rire est le propre de l’homme

”). Erasmus, instead, wrote devastating satire. If the guffaw is a broadsword, satire is a rapier. As such, it always has

a point. Erasmus’s points were missed by the common people, lay as well as clerical, but the coming religious revolution was

not going to be a mass movement. It would be led by the upper and middle classes, which were gaining in literacy every day,

and his brilliant thrusts had the unexpected effect of convulsing them and then arousing them.

In the beginning his intentions were very different. He meant to reach a small, elite audience which would be moved to act

behind the scenes, within the existing framework of their faith. Instead his works became best-sellers. The first of them,

written during his first year in England, was

Encomium moriae

(

The Praise of Folly

). Its Latinized Greek title was partly a pun on his host’s name, but

moros

was also Greek for “fool,” and

moria

for “folly.”

His postulate for the work was that life rewards absurdity at the expense of reason.

C

OMING FROM A MAN OF

G

OD

, it was an astonishing volume. Some passages might have been written by a radical, atheistic German humanist, and had the

author been a man of lesser renown, he would certainly have been condemned by the inquisitors. Being Erasmus, he laughed at

them, daring them to “shout ‘heretic’ … the thunderbolt they always keep ready at a moment’s notice to terrify anyone to whom

they are not favorably inclined.”

He opened his argument by declaring that the human race owed its very existence to folly, for without it no man would submit

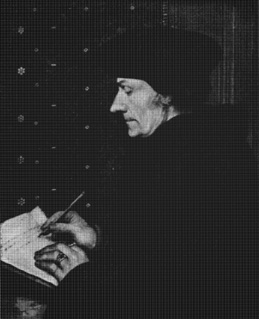

Desiderius Erasmus (1466?–1536)

to lifelong monogamy and no woman to the trials of motherhood. Bravery was foolish; so were men who pursued learning; and

so, he added slyly, were theologians, whom he mocked for defending the absurdity of original sin, for spreading the myth that

“our Saviour was conceived in the Virgin’s womb,” for presuming, during holy communion, to “demonstrate, in the consecrated

wafer … how one body can be in several places at the same time, and how Christ’s body in heaven differs from His body on the

cross or in the sacrament.”

Next he went after the clergy, his targets running up the ecclesiastical scale from friars, monks, parish priests, inquisitors,

to cardinals and popes. To him, curative shrines, miracles, and “such like bugbears of superstition” were “absurdities” which

merely served as “a profitable trade, and [to] procure a comfortable income to such priests and friars as by this craft get

their gain.” He mocked “the cheat of pardons and indulgences.” And “what,” he asked, “can be said bad enough of others who

pretend that by the force of … magical charms, or by the fumbling over their beads in the rehearsal of such and such petitions

(which some religious impostors invented, either for diversion, or, what is more likely, for advantage), they shall procure

riches, honors, pleasure, long life, and lusty old age, nay, after death, a seat at the right hand of the Saviour?” As for

the pontiffs, they had lost any resemblance to the Apostles in “their riches, honors, jurisdictions, offices, dispensations,

licenses … ceremonies and tithes, excommunications and interdicts.” Erasmus, the intellectual, could find only one explanation

for their success: the stupidity, ignorance, and gullibility of the faithful.

Encomium moriae

was translated into a dozen languages. It enraged the priestly hierarchy. “You should know,” one of them wrote him, “that

your

Moria

has excited a great disturbance even among those who were formerly your most devoted admirers.” But few academic writers,

having tasted popular success, can turn away from it, and he was no exception. His faith in the wisdom of his cause was now

confirmed. Indeed, his next satire, which appeared three years later, turned out to be even more startling. This time he assailed

a specific pontiff, “the warrior pope,” Julius II.

Julius had been a strong pope and is remembered, deservedly, for his patronage of Michelangelo. But like all the pontiffs

in that troubled age, he was more sinner than sinned against. He was also a Della Rovere—hot-tempered, flamboyant, and impetuous;

Italians spoke of his

terribilità

(awesomeness). For five years he and his allies fought Venice. This campaign was successful; he recovered Bologna and Perugia,

papal cities which the Venetians had seized during the misrule of the Borgia pope. In his second war, an attempt to expel

the French from Italy, he was less fortunate, though by all accounts he cut a spectacular figure in combat, taking command

at the front, white bearded, wearing helmet and mail, swinging his sword and always on horseback.

In satirizing this formidable pontiff Erasmus neither sought notoriety nor welcomed it; he had tried to deflect personal controversy

by presenting his new work anonymously, but that was a doomed hope. He had shown it to too many colleagues. Sir Thomas More

stripped his friend’s disguise away in a careless moment, and the responsibility was fixed. Within the Catholic hierarchy,

resentment against the author was deepened by what, even today, would be considered questionable taste. The year before the

presentation of Erasmus’s work in Paris—it was a dialogue—Julius had died. Thus the Church was actually in mourning for

the victim of

Iulius exclusus

. Yet this did not dampen the hilarity of the Parisian audience, to whom it was first presented as a skit, or the multitude

of readers in the months and years to come. In his onslaught on the papacy, Erasmus had struck a nerve; his followers thought

the blow long overdue.

Julius is one character in the dialogue; Saint Peter is the other. Both stand at the gates of heaven, where the pope has presented

himself for admittance. Peter won’t let him in. Beneath the applicant’s priestly cassock he notes “bloody armor” and a “body

scarred with sins all over, breath loaded with wine, health broken by debauchery.” To him the waiting pontiff is “the emperor

come back from hell.” What, he asks, has Julius “done for Christianity?”

Heatedly the applicant replies that he has “done more for the Church and Christ than any pope before me.” He cites examples:

“I raised the revenue. I invented new offices and sold them. … I set all the princes of Europe by the ears. I tore up treaties,

and kept great armies in the field. I covered Rome with palaces, and left five millions in the treasury behind me.”

To be sure, he concedes, “I had my misfortunes.” Some whore had afflicted him with “the French pox.” He had been accused of

showing one of his sons favoritism. (“What?” asks Peter, astounded. “Popes with wives and children?” Julius, equally surprised,

replies, “No, not wives, but why not children?”) Julius acknowledges that he had also been accused of simony and pederasty,

but is evasive when asked if his plea is Not guilty, and after Peter, bearing in, inquires, “Is there no way of removing a

wicked pope?” Julius snorts: “Absurd! Who can remove the highest authority of all? … He cannot be deposed for any crime whatsoever.”

Peter asks: “Not for murder?” Julius replies: “Not for murder.” Under questioning he adds that a pontiff cannot lose his miter

even if guilty of fornication, incest, simony, poisoning, parricide, and sacrilege. Peter concludes that a pope may be “the

wickedest of men, yet safe from punishment.” The audience howled, knowing that was precisely Rome’s position.

There is no way Peter is going to let this man into paradise. Julius, apoplectic, tells him that the world has changed since

the time “you starved as a pope, with a handful of poor hunted bishops about you.” When that line of reasoning is rejected,

he threatens to excommunicate Peter, calling him “only a priest … a beggarly fisherman … a Jew.” Peter, unimpressed, replies,

“If Satan needed a vicar he could find none fitter than you. … Fraud, usury, and cunning made you pope. … I brought heathen

Rome to acknowledge Christ; you have made it heathen again. … With your treaties and your protocols, your armies and your

victories, you had no time to read the Gospels.” Julius asks, “Then you won’t open the gates?” Peter firmly replies, “Sooner

to anyone else than to such as you.” When the pontiff threatens to “take your place by storm,” Peter waves him off, astounded

that “such a sink of iniquity can be honored merely because he bears the name of pope.”