A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (130 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

The Southern Independence Association was delighted that the South was finally coming around to Britain’s way of thinking, and they composed a congratulatory address to President Davis on his boldness. To many people, however, the idea seemed far-fetched: nothing but sheer desperation would make them relinquish “the services” of their slaves, Lord Palmerston told John Delane, the editor of

The Times,

“but one can hardly believe that the South [

sic

] men have been so pressed and exhausted.” Delane was inclined to agree, until he learned that General Sherman had reached the outskirts of Savannah. “The American news is a heavy blow to us as well as to the South. It has changed at once the whole face of things,” Delane wrote to his deputy editor on December 25. “I have told Chenery to write upon it.” The next day, he sent another note: “I am still sore vexed about Sherman, but Chenery did his best to attenuate the mischief.”

3

James Spence also tried to play down the news, telling Lord Wharncliffe on January 5, 1865, to look out for his article in

The Times:

“You will find I do not attempt to deny the Federal success in Tennessee or the danger of Savannah, which I assume to be likely to fall [the news of Christmas Eve had not yet reached Britain], but I hope to show that public opinion overestimates the importance of the events and that upon the whole the year’s campaign is a failure on the part of the Federals.” Spence disliked writing such obvious propaganda for the South, “but then,” he reasoned, “it is at such a time—the hour of need—that a friend is of value. When the South is victorious they can do without one’s aid.”

4

The fall of Savannah was not the only disaster that James Spence was trying to present in a more favorable light. His Confederate prisoners’ bazaar had inspired the London office of the U.S. Sanitary Commission to publish a pamphlet on Southern prison conditions.

5

Neither Spence nor Wharncliffe had stopped to consider whether highlighting the plight of Confederate prisoners might backfire if anyone queried the South’s own record, though their campaign had worked so well at first that Mrs. Adams asked Charles Francis Jr. whether it was official policy to mistreat Confederate prisoners.

6

Lord Wharncliffe tried to calm the public outcry by forwarding letters to the press from English volunteers who had suffered in Federal prisons, but it was too late to reverse the damage.

36.1

7

Families with relatives in Southern prisons, including Dr. Livingstone, began to insist that as British subjects they should be released at once under the prisoner exchange system.

8

Another father with a missing son in the Union army, Thomas Smelt, wrote directly to Abraham Lincoln, begging him “as a parent from a parent, that my son may be sent back to me, he has surely fought well and suffered much for your cause and deserves so much.”

9

James Spence did not realize how badly the Southern cause had suffered until

The Times

began to turn down his propaganda articles without explanation. After being met with silence for more than a week Spence conceded that his influence with the paper was at an end. “I doubt if they will insert anything more on the subject,” he wrote to Lord Wharncliffe on January 16. “I see but one thing now that can save the South and that is arming the negroes. Tho, I have always expected they would do it, I am growing fearful lest they invited those fatal words—‘too late.’ ”

10

—

James Bulloch did not accept that time had run out on the Confederacy, especially since—after the disappointments of the previous year—he was experiencing a late surge of success.

11

The

Ajax,

one of two river steamers he had commissioned to defend the entrance to Wilmington, sailed from Glasgow undetected in the second week of January. “It is quite impossible to predict what may have transpired when you reach Nassau,” Bulloch told the captain of the vessel, Lieutenant John Low. “Should [Wilmington] have been taken by the enemy … you will then proceed with the ship to Charleston, SC.… You may find Charleston itself closed to you, in which case there will remain no port on the Atlantic coast of the Confederate States into which you can take the Ajax.” But even then Bulloch wanted Low to find a way to use the ship against the North: at the very least she could bring cotton out from Texas or Florida.

12

He was already thinking of weapons other than cruisers to send across the Atlantic. His two remaining blockade runners, for example, were useless for fighting but could easily be deployed as rocket launchers against fishing towns in New England.

13

Bulloch had also managed to buy back one of the French ironclads that had been sold after the emperor ordered the secret construction program to end.

36.2

The cruiser, which he had decided to christen the

Stonewall,

was coming from Copenhagen, and Bulloch had arranged for a ship with a crew and arms to meet her in neutral waters. After waiting two weeks for news that the transfer had taken place, Henry Hotze suggested to Bulloch on January 25 that they should go ahead and announce the existence of CSS

Stonewall.

It would, he argued, cause panic on the East Coast and force the U.S. Navy to send ironclads to New York, opening the way for the

Stonewall

when she reached Wilmington.

14

Hotze’s

Index

had been heavily advertising the

Shenandoah

’s last known captures for that very reason, unaware that the raider was now anchored at Port Phillip Bay, four miles from Melbourne, bereft of coal and in serious need of refurbishment. The Australians were delighted to be front-row spectators for a change, and thousands were visiting the Bay in the hope that the notorious Captain Semmes of the

Alabama

was the new commander of the

Shenandoah.

15

The diehards had no trouble accepting Hotze’s propaganda. His own staff believed him. John Thompson wrote in his diary: “Am told we shall soon hear something of importance. I think it refers to an ironclad from Europe to attack Boston and New York.”

16

The shipping owner Alexander Collie ridiculed James Spence for being “blue.” “We might be prepared to hear of Wilmington and Charleston being captured, and of Richmond being evacuated,” Collie wrote to Wharncliffe on January 23, “but, in spite of it all, the South will wear the North out and gain its independence.” In the meantime, he was expecting his steamers to begin taking “three or four cargoes monthly for the next four months.”

17

The

Stonewall

was in greater danger than either Bulloch or Hotze knew. Her arrival at Quiberon Bay, on the south coast of Brittany, on January 24 was telegraphed to the U.S. minister in Paris. William Dayton was no longer in charge of the U.S. legation in France, having died under mysterious circumstances in December; John Bigelow, the consul in Paris, had been promoted to his place. A man of far greater intelligence and vigor than Dayton, Bigelow almost succeeded in scuttling the mission by his protests to the French authorities. But one of the worst storms in recent memory ultimately achieved his work for him; on January 29, only a day after the

Stonewall

sailed from Quiberon, the ship’s bridge was smashed to pieces by giant waves. Unable to sail on to Wilmington, Captain Page took the damaged vessel to Ferrol, on the Spanish coast, and waited for repairs. Twenty-four hours later, Europe learned that the Federals had captured Wilmington’s only defense, Fort Fisher.

“Glorious news reached us today,” Benjamin Moran wrote in his diary on January 30, 1865. “The rebels are tired and will come back [into the Union] soon.” Bulloch pressed on, however, and sent an engineer to Ferrol to oversee the

Stonewall

’s repairs. “The fall of Fort Fisher seriously deranges our plans for sending supplies, but all of us who are charged with such duties will speedily consult and make new and suitable arrangements,” he promised Mallory.

18

Mason was also defiant, telling Benjamin that the Southerners in England approved of the Confederate Congress’s declaration on December 13, 1864, to fight on “at whatever cost or hazard.”

19

The Economist

criticized the public’s overreaction to the news of Fort Fisher, since the South “still [has] large armies in the field, they have still the ablest generals of the Republic in their ranks,” but most other papers now declared the Confederacy to be without hope.

20

It was common knowledge that the South would not be able to survive without its imports. During the past four years, 60 percent of the Confederacy’s rifles had come through the blockade, 75 percent of her saltpeter, and 30 percent of her lead, and, particularly after 1862, the blockade runners had become the South’s lifeline.

21

Consul Thomas Dudley in Liverpool had recently completed his statistics for 1864 and amassed evidence against 113 steamships and 304 sailing vessels. Despite the U.S. Navy’s efforts, the South had managed to export 124,700 bales of cotton in return for meat, shoes, arms, medicines, and all the other necessities of war. A total of 303 steamships had successfully run into Wilmington during the war, more than twice the number that reached Charleston.

22

The port had become indispensible to the Confederacy. On February 15, Consul Dudley reported that the blockade-running business had died almost overnight.

It had taken four years and seven hundred U.S. ships at a cost of $567 million to close every Southern port. During that time, there had been 6,316 attempts and 5,389 runs past the blockade. The average capture rate for the whole war was only 30 percent, but this figure hides the increasing success of the Federal navy over time. In 1861, roughly nine out of ten blockade runners reached their destinations, but by 1865 the number was only one in two. Although criticized as inept at the time, it is now clear that the blockade played a vital role in the Northern war effort. Guns, meat, and shoes could be shipped in on the blockade runners, but not the heavy cargoes such as iron rails, telegraph poles, and train carriages that the South needed in order to move its armies, feed its people, communicate over long distances, and transport supplies. These hammer blows to the South cost only 10 percent of the total expenditure of the war; except for Rose Greenhow and a few others, almost no one was killed; and a mere 132,000 sailors were employed by the Federal navy compared to 2.8 million soldiers in the army.

23

—

Mrs. Adams, Henry, Mary, and Brooks left London on February 1 to begin a tour of the Continent. The family had given up the house in Ealing in the expectation that Charles Francis Adams would follow them soon, assuming that Seward would grant his request and appoint a successor. They also were hoping for a visit from Charles Francis Jr., who had surprised them by becoming the colonel of his regiment and proposing marriage to Mary Hone Ogden in the same month.

“Neither

Henry

nor Brooks Adams had the decency to bid me goodbye,” Moran raged in his diary. “I didn’t expect so much civility from the boy, but I did from Henry.” He was equally incensed with his new assistant secretary, Dennis Alward, for ingratiating himself so easily into Adams’s favor. “Mr. Adams is very civil, but it is the smile of the ogre,” he wrote. The minister had wounded Moran to the quick by inviting Alward to ride in his carriage, and, at a reception given by the Countess of Waldegrave, he had taken “special pains to introduce Mr. Alward to everybody and equal pains not to introduce me at all.”

24

Parliament resumed business on February 7. “I have no reason to anticipate any modification in the policy of the ministry toward us,” wrote Mason to Judah Benjamin. “Still, as we have a large body of earnest friends and sympathizers in both houses, it may be that something will arise during the session of which advantage can be taken.”

25

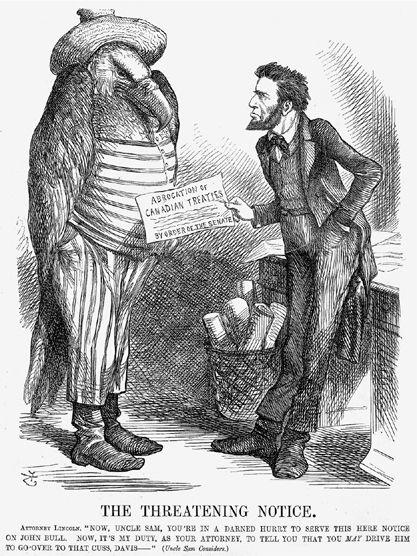

The “something” was the universal consternation over Congress’s repeal of the two treaties with Canada, particularly the Rush-Bagot Treaty, which limited the naval power on the Great Lakes. The hysteria over the issue in Parliament alarmed Adams, who warned Seward on February 9: “The insurgent emissaries and their friends are busy fanning the notion that this is a prelude to war the moment our domestic difficulties are over.” With uncharacteristic force, he charged the secretary of state to remember that the future of Anglo-American relations lay in his hands.

26