A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (133 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

The Confederate Congress was holding what would turn out to be its last session when Conolly returned to Richmond on March 18. Four days earlier, the politicians had agreed to allow owners to volunteer their slaves as soldiers, having voted unanimously “to prosecute the war with the United States until … the independence of the Confederate States shall have been established.” But today the members adjourned with no thought of when they would meet again.

13

The city was tense and quiet as the residents waited to learn whether General Johnston would stop Sherman’s advance now that Fayetteville had fallen to the Federals. “If Sherman cuts the communication with North Carolina,” wrote John Jones, “no one doubts that this city must be abandoned by Lee’s army.”

14

“We are falling back slowly before Sherman,” Feilden had scribbled in a penciled note to Julia on March 13. “I hope that we may have a victory over this man Sherman. I should like to pursue him from here to South Carolina.”

15

None of the Confederate generals, including Hardee, had expected Sherman to make it through the Carolina swamps so quickly, if at all. The right wing of Sherman’s army was within marching distance of Raleigh, North Carolina’s capital. In desperation, Hardee deployed his outnumbered and weakened forces in a surprise attack against Sherman’s left flank on March 16.

The ambush slowed Sherman just enough for Johnston to organize his army into battle formation at Bentonville, North Carolina. There, for three days, beginning at dawn on March 19, 1865, a force of twenty thousand Confederates struggled against an army three times its size. The disparity between the two armies was exacerbated by the Confederates’ muddled organization, but Johnston suddenly showed his critics that he could fight—and fight hard—when pressed. By March 21 Johnston’s army had suffered more than twenty-five hundred casualties, to the Federals’ fifteen hundred. Feilden was talking to General Hardee when a stray shot struck the tree beside them. The next bullet passed through Feilden’s sleeve “near enough to jar my funny bone” and hit his horse, Billy, in the leg. The wound was just bad enough to prevent him from riding the horse in the next cavalry charge. Hardee’s sixteen-year-old son, Willie, begged to take part, and in the heat of the moment, Hardee nodded his assent and kissed the boy farewell. A short while later, a Texas Ranger brought Willie back, shot through the chest. “He was a mere schoolboy,” wrote Feilden in anguish. “He was as gallant a little fellow as ever fired a musket.” The tragedy made him long to be with Julia: “Oh! My precious one, if we are only spared to meet again, and live together, what happiness it will be,” he wrote. “I don’t care how poor we may be. It will be the greatest blessing this earth can afford us.”

16

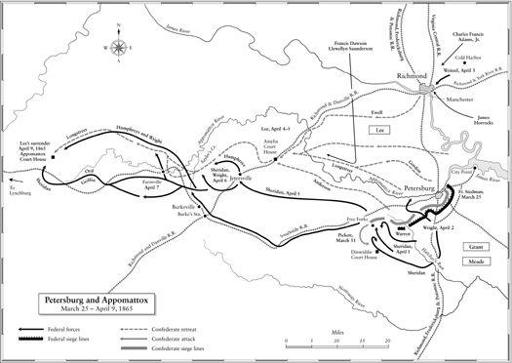

After the Battle of Bentonville, Sherman continued his march toward Richmond while the Confederates retreated to Raleigh, North Carolina—Johnston apparently too stunned to consider pursuit. He telegraphed Lee: “Sherman’s course cannot be hindered by the small force I have. I can do no more than annoy him.” Lee realized that in a few days he would be facing the combined forces of Grant, Sheridan, and Sherman, and he began planning the Army of Northern Virginia’s evacuation from Petersburg. He knew that Richmond would then fall to the Federals, but if his army remained intact, the South would still have its fighting capability. On March 25, he launched a surprise attack against the Union Fort Steadman, on the east side of Petersburg, hoping to distract Grant long enough to enable the rest of the Confederate army to retreat southward, toward North Carolina. The assault was an outright disaster, costing Lee four thousand casualties against the Federals’ fifteen hundred, without any weakening of Grant’s line.

Thomas Conolly was in Richmond during the attack, but the news of its failure made no difference to his confidence in the ultimate outcome of the war: “Richmond thy sun is not setting, rather the Day is just about to break over your hero-crested virgin hills!” he wrote in his diary, adding for good measure: “Always darkest before the dawn! What a dawn, Independence!” Late on the twenty-fifth he received a note inviting him to visit Mrs. Mason’s house. “ ‘Welly’ is to be there!” wrote Conolly in surprise, learning for the first time that his friend Lieutenant Llewellyn Traherne Bassett Saunderson, of the British Army’s 11th Hussars, had arrived in the South at the same time as he had, hoping to volunteer on General Lee’s staff.

17

The following day, March 26, Conolly went to church, where the vicar’s sermon put him to sleep; “I hate argument, I like faith much better!” Conolly was oblivious to the fact that the city was emptying around him. Jefferson Davis had overridden his wife’s protests and instructed her to take the family to Charlotte, North Carolina, three hundred miles to the southwest, and to go farther if necessary. Their furniture was sent to auction, and Varina distributed various mementos to friends and servants. Davis also asked his private secretary to accompany the family to safety. He gave Varina all his gold save for one five-dollar piece and a small Colt pistol, which she was to use in the “last extremity.”

CSS

Georgia

’s former lieutenant James Morgan met the Davis family at the station. In his wildest dreams he had never imagined himself as personal guard to a mother and her small children. When summoned by the Confederate navy secretary, Stephen Mallory, to the Navy Department, he thought it was for some infraction: “I at once began to think of all my sins of commission and omission. To my surprise, he told me that I was to accompany Mrs. Jefferson Davis south, and added, with a merry twinkle in his eyes, that the daughters of the Secretary of the Treasury [George Trenholm] were to be of the party.” (Morgan had become engaged to Trenholm’s younger daughter, Helen, whom he met in Charleston the night of his introduction to Matthew Fontaine Maury.)

As Morgan observed the parting between Jefferson and Varina, he realized that the Davises were behaving as though it was their final moment together as a family. The two eldest children clung to their father, crying to stay with him. Davis kissed them all again, stroked the baby that lay asleep on a bench, embraced his wife, wished Morgan and the Trenholm girls a safe journey, and walked heavily down the carriage steps. What should have been a six-hour train journey took more than four days. When the creaking train pulled into Charlotte, a furious mob surrounded the carriage:

I closed the open windows of the car so that the ladies could not hear what was being said [recalled Morgan]. We two men were helpless to protect them from the epithets of a crowd of some seventy-five or a hundred blackguards, but we stationed ourselves at the only door which was not locked, determined that they should not enter the car. Colonel Harrison was unarmed, and I had only my sword, and a regulation revolver in the holster hanging from my belt. Several of the most daring of the brutes climbed up the steps, but when Colonel Harrison firmly told them that he would not permit them to enter that car the cowards slunk away. When the disturbance had quieted down Mrs. Davis, her sister, and her children left the train.

The city’s residents were frightened of showing courtesy to Varina and furious with her husband for mismanaging the war. “Mrs. Davis would have been in a sad plight if it had not been for the courage and chivalric courtesy of a Jewish gentleman, a Mr. Weil,” wrote Morgan, “who hospitably invited her to stay at his home until she could make other arrangements. May the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob bless him wherever he is!”

18

Jefferson Davis waited anxiously in the Confederate capital while Lee sought to delay Grant’s encirclement of Petersburg. The Army of Northern Virginia had dwindled to no more than 35,000 men, while Grant’s Army of the Potomac had grown to over 125,000. President Lincoln was less than twenty miles from Richmond, having traveled from Washington on the

River Queen

to visit Grant’s headquarters at City Point on the James River. (Mary and Tad accompanied him for the first days, but Mary behaved so strangely—raving at the slightest provocation—that she was encouraged to stay in her cabin.) Lincoln’s greatest concern was that peace, which seemed so close now, should not be a pyrrhic victory for the North. “I want no one punished,” he told Sherman and Grant. Their armies were to be restrained from violence or vengeance. When asked about President Davis, Lincoln expressed a wish that the Confederate leader would emigrate, unnoticed and unmolested.

—

Lee and Grant had fought each other over seven hundred square miles of territory since June 9, 1864; more than seventy thousand soldiers had died in nineteen separate battles. Now, the struggle had narrowed to the possession of the Five Forks crossroads, fifteen miles from Petersburg. Lee needed to hold it just long enough for his forces to escape from Petersburg using the Southside Railroad. Tom Conolly was again at Lee’s headquarters, where he watched the general outline the battle plan to his staff, using a stick and a “mud map.” Conolly remained with Lee rather than following Generals Fitz Lee and George Pickett to Five Forks, and he was rewarded with the spectacle of a skirmish between two picket lines:

This pleased [Conolly] so much, [wrote General Wilcox] that he offered his service to me for the coming campaign, and said if I would permit him he would remain with me until its close. I accepted his tender of service, and told him I would make him one of my volunteer aides. He thanked me, and asked if I would let him go under fire. I replied that it would hardly be possible for him to escape being under fire. He said he would return to Richmond, get his baggage and report to me early Monday morning [April 3].

19

At Five Forks, Fitz Lee and Pickett had orders to hold the crossroads “at all hazard.” Welly had been placed on Fitz Lee’s staff, where he was delighted to discover another British volunteer, Francis Dawson. They rose at 3:30

A.M.

on March 31, and “after a rough breakfast we all went down to General Pickett’s headquarters where a Council of War took place. We remained here for 3 hours or so, smoking and telling stories in a downfall of rain the whole time.”

20

Years afterward, Dawson also remembered the terrible rain that had chilled him to the bone. He had tried to keep warm by gulping coffee out of an old tin cup before the fighting commenced, scalding his lips in the process. Later in the morning another moment seared itself in his memory. “It was very difficult to rally the men,” he wrote:

One fellow whom I halted as he was running to the rear, and whom I threatened to shoot if he did not stop, looked up in my face in the most astonished manner, and, raising his carbine at an angle of forty-five degrees, fired it in the air, or at the tops of the pines, and resumed his flight. It made me laugh, angry as I was.

21

Toward sundown, General Fitz Lee’s men made a final, desperate charge against Sheridan’s line. One bullet struck an overhanging branch just as Dawson lowered his head to ride under the tree; the next tore into his shoulder.

“Bad news from Pickett,” recorded Welly on April 1. “He has lost 5,000 men out of 8,000, and the remainder are cut off from us.” The two generals, Fitz Lee and Pickett, had ridden off to a picnic, having assumed that Sheridan would spend the day entrenching his men. Far from it: Sheridan launched a surprise attack. “We had no idea that the enemy were so close to us,” wrote Welly, “when all of a sudden about 250 Yankees let drive at us, it was so sudden that nobody could help being startled. I looked round and the whole regiment had disappeared.” Sheridan captured more than four thousand prisoners at Five Forks. As the scattered Confederates found one another, Welly was relieved to learn that “Dawson, one of my brother ADCs,” had not been killed, but sent to Richmond at Fitz Lee’s insistence.

22

Dawson arrived in the city so befuddled with morphine that he was oblivious to the turmoil in the streets. At dawn on Sunday, April 2, Grant ordered an all-out attack on Lee’s defenses, smashing through at almost every point. Lee realized he had to retreat immediately or risk being surrounded and captured. He ordered the troops to evacuate and sent a telegram to Davis advising him to leave Richmond. The message was delivered to Davis while he was at church. Conolly was sitting in a pew nearby and observed the sexton whisper in his ear. “He rises and leaves the Church. Then the same operation to one and a second member of the government, both follow suit; people begin to whisper … they rose in tens and 20s and left the Church, outside the secret was soon abroad.” Only the most faithful remained for communion. Conolly fought his way through the streets—“a regular stampede has begun”—to the home of his friends Mrs. Enders and “her nice pretty daughters.” He promised the distraught women he would spend the night, guarding the house for them. Having satisfied himself that they were safe for the moment, Conolly set off in search of Francis Lawley and found him packing his bags at the hotel: “We take a parting cup to our next merry meeting.”