A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (137 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

—

Jefferson Davis finally accepted defeat on May 3. He had been constantly on the move since leaving Greensboro on April 14, and he had reached Washington, in northeast Georgia. Right up until the day before, Davis had insisted to the cluster of cabinet members and generals surrounding him that resistance was not just possible but also a duty. He had carried on the normal functions of government, issuing orders and signing papers—albeit by the roadside instead of at his desk—as if it would only be a matter of time before the Confederacy was made whole again. Frank Vizetelly was present to sketch him doing so. “This was probably the last official business transacted by the Confederate Cabinet and may well be termed ‘Government by the roadside,’ ” the war artist wrote next to his drawing.

“Three thousand brave men are enough for a nucleus around which the whole people will rally when the panic which now afflicts them has passed away,” Davis had told a member of his cavalry escort. The officer was speechless for a brief moment before replying that the three thousand troops guarding the Confederate president would risk their lives to save his, “but would not fire another shot in an effort to continue hostilities.… Then Mr. Davis rose and ejaculated bitterly that all was indeed lost. He had become very pallid, and he walked so feebly as he proceeded to leave the room that General Breckinridge [the new Confederate secretary of war] stepped hastily up and offered his arm.”

40

Even then, Davis did not relinquish all hope. A few hours later he was approached by Lieutenant James Morgan of CSS

Georgia,

who had come in search of him after Varina Davis had relieved him of his escort duty.

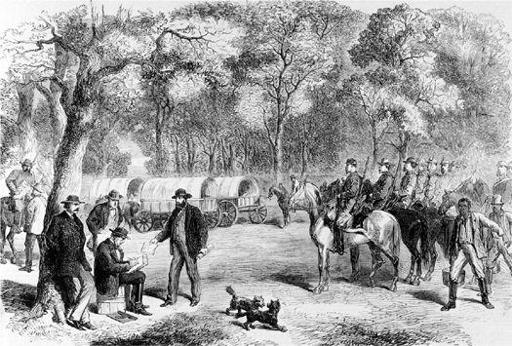

Ill.62

Jefferson Davis signing acts of government by the roadside, by Frank Vizetelly.

I begged him to allow me to accompany him, but he told me that it would be impossible, as I had no horse. He spoke to me in the most fatherly way, saying that as soon as things quieted down somewhat I must make my way to the trans-Mississippi, where we still had an army and two or three small gun-boats on the Red River, and in the mean time he would give me a letter to General Fry, commanding at Augusta, asking him to attach me temporarily to his staff.

41

The Confederate cabinet began to break up as soon as the fugitives crossed into Georgia on the third. They were worn down by fatigue and fear. “I am as one walking in a dream, and expecting to wake,” wrote General Josiah Gorgas.

42

Vizetelly drew one last picture of the complete party as it rode through the woods, and then Gorgas, Benjamin, and Mallory all set out on their own. A novice rider, Benjamin was physically incapable of keeping up with Davis and had struggled for the past few days. He assumed the disguise of a French businessman, bought a horse and buggy, and went off in the direction of Florida, where he hoped to take passage on a boat to the Caribbean.

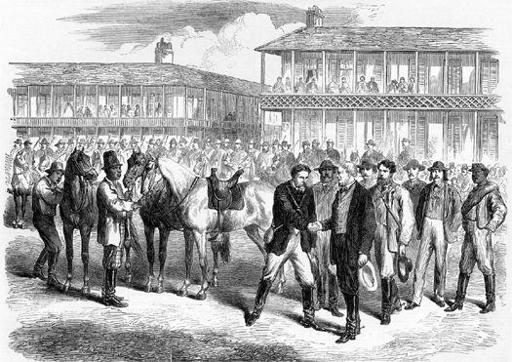

“I saw an organized government … fall to pieces little by little,” wrote Captain Micajah Clark, Davis’s former private clerk, who had been placed in charge of the Confederacy’s traveling treasury three days earlier. Vizetelly’s final sketch showed Davis in Washington, Georgia, on May 4, shaking hands with the officers of his guard. “It was here that President Davis determined to continue his flight almost alone,” wrote Vizetelly. “With tears in his eyes he begged them to seek their own safety and leave him to meet his fate.” The journalist thought that Davis had been “ill-advised” to travel with so large a retinue when there was a $100,000 bounty on his head.

Ill.63

Flight of Jefferson Davis and his cabinet over the Georgia Ridge, five days before his capture, by Frank Vizetelly.

With the postmaster general, John H. Reagan, his three aides, and a small cavalry detachment, Davis headed southward, expecting to catch up with Varina and the children in a day or two. He hoped that the wagons carrying the last of his government’s funds—$288,022.90 in gold and silver coins—would reach a port and from there be transported to England, where it could be used to fund Southern resistance against Washington.

38.6

Davis, now realizing the extreme folly of attracting attention, made up a new identity as a Texas politician on his way home. Vizetelly’s continued presence only endangered the party, and the journalist accepted that it was time for him to leave. Just before he rode away, sometime on or shortly after May 5, Vizetelly pressed a £50 note into Davis’s hand, which would be enough to pay for the entire family to sail to England, third class.

43

The next time Vizetelly had a report of the president’s progress was from the news wires, announcing Davis’s capture on May 10. The Federal commander at Hilton Head, South Carolina, signaled:

Jeff Davis, wife, and three children; C C Clay and wife, Reagan, General Wheeler, several colonels and captains, Stephens (late Vice-President) are now at Hilton Head, having been brought here from Savannah this afternoon. They were captured by 130 men, 5th Michigan Cavalry, 120 miles south of Macon, Ga, near Irwinville. They had no escort, and made no resistance. Jeff. looks much worn and troubled; so does Stephens.

44

The new British minister, Sir Frederick Bruce, informed London of the development. “There is no doubt that the Confederacy as a political body is at an end,” he wrote to Lord Russell. He strongly advised that Britain refuse port entry to the two Confederate cruisers still at large unless she desired to irritate the U.S. government. “The moment is a critical one,” Bruce warned on May 16.

45

CSS

Stonewall

had tried to obtain coal at Nassau and been sent on her way. The ship managed to make it to Havana, where its presence embarrassed the authorities for a few days until definitive news arrived of the Confederacy’s collapse.

38.7

Ill.64

Jefferson Davis bidding farewell to his escort two days before his capture, by Frank Vizetelly.

Bruce had been in Washington since April 8, although he had not yet been presented to Lincoln when the president was assassinated on April 14. Since then, Bruce had waited anxiously to learn what the new administration’s attitude would be toward Britain. A large banner had been draped across the State Department building proclaiming

PEACE AND GOOD WILL TO ALL NATIONS, BUT NO ENTANGLING ALLIANCES AND NO FOREIGN INTERVENTIONS,

which did not inspire him with confidence.

47

He was relieved when President Johnson went out of his way to reassure him of his cordial feelings toward Britain.

48

“I have not been accustomed to etiquette,” Johnson admitted when Bruce was presented to him, “but I shall be at all times happy to see you and prepared to approach questions in a just and friendly spirit.”

38.8

Charles Sumner had offered to be an intermediary between the British legation and the president, but Bruce was loath to call upon him despite his admiration for the senator’s historic battle against slavery. There was something about Sumner’s insistence that no one else in Washington was capable of discussing foreign affairs that made Bruce doubt his motives. “It struck me,” wrote Bruce, “that the drift of his conversation was to lead me to the conclusion that I should enter into confidential communication with himself. This I am reluctant to do, as long as there is hope of Mr. Seward being able shortly to resume his duties.” He disliked “the want of frankness in him” and suspected that Sumner was trying to discover his weaknesses in order to exploit them later.

50

Bruce could see that the overwhelming desire in the country was for peace, and he no longer feared for the safety of Canada, although there were still serious frictions between Britain and America that remained unresolved. “The feeling against blockade runners, and foreigners who have served in a civil or military character in the South, is so strong as to make a fair trial almost hopeless,” he wrote to Russell. “These cases require great delicacy in handling—for to insinuate unfairness on the part of the officers composing their Military Commissions, would render the execution of a sentence only more certain.” Reflecting on Colonel Grenfell, who had been the only defendant in the Chicago conspiracy trial to receive the death sentence, Bruce thought that people were “against leniency where a foreigner is concerned and the Government will not openly thwart the popular sentiment in that respect.”

51

Bennet Burley’s trial would take place soon, and Bruce expected a similar outcome.

Bruce felt pity for the defeated South, but his overriding fears were for the colored population of the United States, whose future seemed so uncertain. “The antagonism [against] the Negro breaks out constantly,” he wrote to Lord Russell. In Manhattan, a delegation of black New Yorkers was denied the right to walk behind Lincoln’s funeral cortege. When the White House intervened, a police escort had to protect the black marchers from the violence of the mob. “At Philadelphia,” continued Bruce, “though the Abolition element is strong, the pretension of the coloured people to ride in the railway cars [is] strenuously resisted, and threaten[s] to end in serious riots.” He had also heard that Tennessee had barred the testimony of black witnesses except in trials involving black defendants.

52

Many Southerners assumed that Northern fury would result in the execution of all the leading Confederates. Henry Feilden had heard that President Johnson was “burning with hatred against the South” (which was untrue, though Johnson did exclude owners of plantations worth more than $20,000 before the war from pardon), yet his own experiences showed him there was hope of eventual reconciliation between the two sides. He encountered mostly kindness from Federal troops as he slowly made his way to Charleston. Two Northern officers “acted as well as they could and were as kind and accommodating as possible,” he told Julia. “For instance they insisted on paying all the expenses. We helped them to drink three bottles of whiskey en route. At Branchville they got the US officer to put our horses on the car and saved us 65 miles ride. By the way,” he added, “the 102nd US Colored troops gave us lunch there.”

53

President Andrew Johnson proclaimed a general amnesty on May 29, 1865, three days after the surrender of the last Southern army in the field, General Edmond Kirby-Smith’s Army of the Trans-Mississippi. The war was officially at an end, but for many people it was not over. During the past four years, Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell had rarely been absent from her work, training nurses at the New York Infirmary for Women; she tried to explain her state of mind to Barbara Bodichon, her friend in England: