A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (67 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

But once Hartington reached Virginia, it took less than a week for him to be won over. Like Frank Vizetelly and Francis Lawley before him, he was smitten. “I hope Freddy [his younger brother, Lord Frederick Cavendish] won’t groan much over my rebel sympathies, but I can’t help them,” he wrote to his father on December 28, 1862. “The people here are so much more earnest about the thing than the North seems to be, that it is impossible not to go a good way with them, though one may think they were wrong at first.”

68

The Southerners were certainly putting on a good show for him. He was introduced to Jefferson Davis and his cabinet, who seemed like moderate and sensible men to him, fighting the laudable cause of self-determination; he had spoken with Lee and Jackson, who were modest in victory; and he had been shown a couple of carefully selected plantations. “The negroes hardly look as well off as I expected to see them,” he wrote afterward, “but they are not dirtier or more uncomfortable-looking than Irish labourers.” Southern fears of a “servile insurrection” inspired by Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation had proved to be unfounded.

15.5

69

On the twenty-ninth, Lawley accompanied Hartington and Colonel Leslie to General Jeb Stuart’s headquarters. Forewarned by a telegram from Lawley, the officers ransacked their own belongings to provide the party with comfortable accommodation. Scarce luxuries like blankets and stoves were sacrificed for the visitors. The fattest turkey in the camp was killed and plucked for dinner. Hartington appreciated their efforts, and he endeared himself to his hosts by insisting “we should not make any change for them in our ordinary routine, but let them fare exactly as the rest.” To demonstrate his sincerity he helped to beat the eggs for “a monster egg-nog.”

70

But as Hartington joined in the revelries, he suddenly realized the scale of suffering it would require to crush the spirit of rebellion. The South “can never be brought back into the Union except as conquered provinces,” he wrote, “and I think they will take a great deal of conquering before that is done.”

71

15.1

The previous incumbent, William Brodie, had pleaded with the Foreign Office to send him anywhere so long as he could escape Washington.

15.2

Jeb Stuart took a grim satisfaction from Wynne and Phillips’s reports: The “Englishmen here,” he wrote to General Lee’s eldest son, George Washington Custis Lee, “who surveyed Solferino [the battle that inspired Henry Dunant to found the Red Cross] and all the battlefields of Italy say that the pile of dead on the plains of Fredericksburg exceeds anything of the sort ever seen by them.”

15.3

Seward’s printed correspondence provided some of the most interesting reading the Foreign Office clerks had seen in years. But Lord Lyons adopted a judicious view of the letters. “[Seward’s] tone towards the Foreign Powers has, however, become much more civil than it appeared in the correspondence printed last year,” he pointed out to Lord Russell. As for Adams and his indiscreet comments, Lyons thought he showed “more calmness and good sense than any of the American Ministers abroad. He is not altogether free from a tendency to small suspicions—but this, I think, proceeds from his position, not from his natural character—it is, too, a very common mistake of inexperienced diplomats.”

55

15.4

The line that really upset Sumner was this: “The extreme advocates of African slavery and its most vehement opponents were acting in concert together to precipitate a servile war—the former by making the most desperate attempt to overthrow the federal Union, the latter by demanding an edict of universal emancipation.”

56

15.5

In New Orleans, Acting Consul George Coppell had tried to obtain permission for British subjects to arm themselves in case of a race riot against whites.

SIXTEEN

The Missing Key to Victory

New Year’s Day—Heartbreak at Vicksburg—General Banks assumes command at New Orleans—The

Alabama

embarrasses the U.S. Navy—Seward returns to his old ways

T

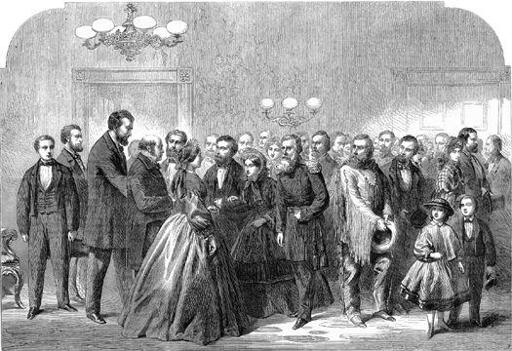

he English volunteer Dr. Charles Mayo finally took a break from work on New Year’s Day to attend a public reception at the White House. By the time he reached the front of the queue outside the Blue Room, Lincoln had been shaking hands for more than two hours without a break. “His presence is by no means majestic,” wrote Mayo, “and I could not but pity the poor man, he looked so miserable.”

1

A journalist observing the occasion wrote that Lincoln’s gait had become “more stooping, his countenance sallow, and there is a sunken, deathly look about the large, cavernous eyes.”

2

The president had also hosted the official reception for dignitaries, foreign diplomats, and politicians earlier in the day. It was the only occasion when the ministers were expected to wear their dress uniforms to the White House. Notwithstanding the finery on display, the atmosphere had been subdued. Seward hardly left Lincoln’s side, Lyons noticed, and made no attempt to engage his colleagues in conversation.

Once the White House had emptied, Lincoln could concentrate on the immediate problem at hand: General Burnside had called in the morning to offer his resignation. Though the president had lost confidence in Burnside’s capabilities, he was not sure that it would be right to give the Army of the Potomac its third leader in three months. Over the past few days, telegrams had been arriving from out west that filled him with anxiety. The Federal armies in Mississippi and Tennessee both appeared to be on the brink of defeat.

Ill.30

New Year’s Day reception at the White House, by Frank Vizetelly.

—

Only five months earlier, Lincoln had complained that Europe concentrated far too much on the North’s failures in the East and entirely ignored the great successes it enjoyed in the West, where Federal armies were “clearing more than a hundred thousand square miles of country.”

3

But since then, the U.S. Navy had been unable to take control of the Mississippi River, and General Grant had failed to capture the river port of Vicksburg, his next objective. For as long as Vicksburg stayed in Confederate hands, the mighty Mississippi remained the South’s most precious supply route and means of communication between its eastern and western parts. The significance of the river as the economic backbone of America was no mere story to Lincoln; during his youth he had worked on it, traveling on flatboats from Illinois down to New Orleans. “Vicksburg is the key,” he had told his generals in 1861. “The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket.… We can take all the northern ports of the Confederacy, and they can defy us from Vicksburg.”

16.1

4

Since that discussion, the Federal army had grown to just under a million men, twice the Confederate total of 464,000. Lincoln wanted this numerical superiority exploited; a week of Fredericksburgs would wipe out Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia but cause only a dent in the North’s fighting capacity.

Vicksburg was roughly equidistant between Memphis, Tennessee, and New Orleans; the next fort was Port Hudson, 150 miles farther south, which guarded the approach to Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Nicknamed the “Hill City” before the war, but now referred to as the Gibraltar of the Mississippi,

16.2

Vicksburg owed its defensive strength to the spectacular geography of the Mississippi Delta. Situated along a sprawling chain of hills overlooking a sharp bend in the river, surrounded by alligator-infested swamps and densely wooded bayous whose emerald-colored waters obscured a netherworld of poisonous snakes and snapping turtles, Vicksburg afforded few approaches that could not be defended from the town. Before the war, Vicksburg had been a thriving commercial center of four thousand inhabitants, with six newspapers, several churches of different denominations, and even its own synagogue. But now its purpose was simply strategic, to be defended or captured at all costs.

The lack of progress in opening up the Mississippi River had political and military implications that Lincoln could not afford to ignore. The Democratic politician turned general John McClernand warned that if control of the river were not soon achieved, the Midwestern states of Ohio, Illinois, and Indiana might lead a second mass exodus from the Union, creating a separate Confederacy of the Northwest, which would make its own peace with the South.

There was also the problem of General Ben Butler down in New Orleans. His eight-month rule had resulted in a profoundly alienated population as well as a raft of missed opportunities to gain more of the Mississippi. Lincoln decided to replace Butler with another political general, Nathaniel P. Banks. Though his military record was not inspiring—Stonewall Jackson had thrashed his first army in the summer of 1862—Banks was a popular and respected Massachusetts politician. From humble beginnings as a bobbin boy in a cotton factory, he had risen through his own talents to become the Speaker of the House of Representatives. Banks’s leadership qualities were not in question, nor was his honesty—an important consideration after the accusations of corruption leveled against Butler.

The immaculately dressed and well-spoken Banks (he had carefully erased all traces of his working-class roots) appeared to be the perfect choice. His political connections meant that he had no trouble working with the governors of New York and New England to recruit an entirely new army of volunteers; he had already displayed his tact and administrative skills after he was sent to quell unrest in Maryland in 1861; and he was ambitious for military glory. Lincoln gave Banks two objectives when he asked him to go to New Orleans in November 1862. Militarily, the general was to lead his army up the Mississippi, sweeping away Confederate resistance as he proceeded, until he joined forces with General Grant at Vicksburg, some 225 miles to the north. Politically, he was to ensure the election of a new, pro-Northern legislature in Louisiana that would enable the state to be readmitted to the Union.

Lincoln adopted the same pragmatic approach when General McClernand asked permission to raise an army of volunteers from the Midwest with the sole aim of attacking Vicksburg. The president believed that the political gains to the administration from McClernand’s project outweighed any potential annoyance that might be felt by the army chiefs.

However, Lincoln underestimated how much Halleck and Grant—neither of whom had any liking for enthusiastic amateurs, regardless of their political usefulness—would resent the encroachment on their authority. Grant immediately made plans to reach Vicksburg before McClernand. He ordered his trusted lieutenant William T. Sherman to take 33,000 men and sail down the Mississippi to about fifteen miles north of Vicksburg, where he was to leave the river and enter its tributary, the Yazoo. There was a bluff along a bend in the Yazoo that was easy to scale and would allow Sherman to follow an overland route to the town. Grant intended to march toward Vicksburg with the rest of the army, luring the Confederates into a battle and thus leaving the way open for Sherman. The operation began on December 20, 1862, as a fleet of troopships, floating hospitals, and gunboats set sail from Memphis. But while Sherman was traveling downriver, Confederate raiders destroyed Grant’s supply base, forcing him to turn back toward Tennessee. Sherman continued on his mission unaware that he would be facing the enemy alone.

The floating attack force came to a halt on Christmas Day, a few miles short of the proposed bluff. The sinking of a gunboat, USS

Cairo,

revealed the existence of underwater mines around an area of the Yazoo known as Chickasaw Bayou. Still ignorant of Grant’s return to base, Sherman decided to alter his plan slightly and disembark at Chickasaw. There was more swamp than dry land here, but above the bluffs were the Walnut Hills and a road that led straight to Vicksburg. Sherman was not fazed by his first solo mission under Grant; he knew that the Walnut Hills were largely devoid of Confederate troops, and assumed that the taking of the bluffs would be achieved in a matter of hours.