A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (69 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Whether Currie was capable of commanding the unruly 133rd remained to be seen. Already furious at having been assigned to a foreigner, the regiment saw nothing positive about being in New Orleans. The women still turned their backs and scowled at the slightest provocation. The male inhabitants seemed to divide into two distinct species: those who wished to fleece them and those who were waiting for an opportunity to kill them. The city was like a poisonous flower: beautiful to behold but dangerous to touch. General Butler had cut down the murder rate, but every other vice had been allowed to flourish. General Banks was appalled to discover that many of the stories that had reached him were true. Federal officers treated private property in the Crescent City as theirs for the taking. A family might receive an eviction notice with orders to move out the same day, taking nothing except clothes and necessities. The occupier would move in the following day, and the plundering would begin.

The Scotsman William Watson observed Banks’s attempt to impose civic order on the city and almost felt sorry for him. The Northerner was, wrote Watson, “altogether too mild a man to grapple with the state of things then existing in New Orleans.”

21

“Everybody connected with the government has been employed in stealing,” a horrified Banks wrote to his wife in mid-January. “Sugar, silver plate, horses, carriages, everything they could lay their hands on.” He also discovered that nothing happened without a bribe. Among his first directives was an order for all officers to leave civilian accommodation and return to army quarters.

22

Mary Sophia Hill had recently returned to New Orleans carrying hundreds of messages and letters for the marooned families of Confederate soldiers, and was similarly appalled by the moral degradation that had spread through the city.

The 133rd was sent north to Baton Rouge, where Currie did his best to continue training the men, teaching them the rudiments of drill. By the end of January he was just beginning to make some headway when he learned that the War Department had received serious allegations against him. A former member of the regiment had been trying to persuade his old colleagues to make a joint protest against Currie. When he failed to whip up enough support, he went ahead on his own, concocting an absurd list of crimes allegedly committed by the colonel. Currie knew he would be exonerated if the authorities questioned his fellow officers, but he recoiled at the thought of an investigation. It would, he was sure, undermine his hard-won authority. Moreover, he found the whole affair deeply offensive. “I have been engaged in a humble way, but to the best of my ability in suppressing rebellion, and maintaining constitutional government, which is scarcely compatible with such charges,” he wrote to his superiors; “if, after a life of fourteen years of active employment in a profession of honour, my character requires defence, it is not worthy of it.” They agreed. On February 4, 1863, Currie’s commander declared that no attention should be paid to the allegations.

23

Currie’s exoneration was followed by an order to lead a scouting expedition through the bayous west of Baton Rouge. After Vicksburg, the Mississippi River meandered for about 150 miles until it reached another deep bend carved into eighty-foot-high bluffs. Here the little town of Port Hudson was perched on top of the eastern bank, the perfect site for heavy artillery to bombard enemy ships as they slowed down to navigate the sharp turn. The bastion not only kept the Federal army bottled up between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, it also protected the Confederates’ chief supply route west of the Mississippi. The romantically named Red River, so called for the rust-colored clay along its northern banks, flowed from the corner of northern Texas all the way down and across Louisiana, finally emptying into the Mississippi just above Port Hudson. It passed through some of the most fertile regions of the Confederacy. If Banks could take Port Hudson, he would also have the Red River, its grains and cattle, and, most important of all, its rich cotton plantations.

Since Banks could not approach Port Hudson from the Mississippi, he wondered if he could bypass the area altogether by finding a way through the mazelike bayous and lesser tributaries that fed the river. Currie’s regiment was sent on a two-week trek through densely wooded swamps and across alligator-infested rivers. They were prey not only to the wildlife but also to local Confederates who lay in wait for them. One private was killed and two others were snatched during an ambush. The men returned at the end of February, nervous and physical wrecks. They were “used up,” in Currie’s words: “In my opinion the country is impracticable for all arms of the service.”

24

There was no alternative but to face Port Hudson’s batteries. General Banks invited his naval counterpart, Admiral Farragut, to his headquarters at the palatial St. Charles Hotel to discuss a joint assault. The general knew that his troops were no match for a seasoned Confederate army, but they could provide cover for Farragut’s warships. Banks would attack Port Hudson from the land, hopefully causing enough confusion to allow the navy to steam up the river. The great question hung on Banks’s ability to deliver a solid enough diversion.

25

Just how green some of his troops were had been demonstrated on February 20 when a small detachment sent to the levee to oversee the departure of Confederate prisoners bound for Baton Rouge was responsible for a disgraceful incident. As word spread through the city that rebel officers were being escorted onto steamboats, thousands of well-wishers, most of them women and children, ran down to see them off. Mary Sophia Hill was among them. Weeping and cheering, they waved red handkerchiefs in mass defiance of the order against displays of Confederate sympathy. The Union troops soon lost control of the crowd, which heaved and swayed with emotion. Panicking, the Federal officer in charge sent an urgent request for more troops, who arrived with bayonets fixed. They came “at a canter,” recalled Mary. “The guns were rammed and pointed at this helpless mass of weakness.” The women were literally beaten back from the levee. “As I never yet ran from an enemy,” she continued, “but always faced them, I walked backwards, with others, to some warehouses, where we were again chased by Federal officials in uniform.”

26

No one was killed, but there were cuts and broken bones; and with every retelling the officers became more brutal and the danger more desperate. Once again the Northern occupiers had succeeded in presenting themselves in the worst light. Southern newspapers sarcastically labeled the affair

“la bataille des mouchoirs”

(the battle of the handkerchiefs). Banks’s reputation plunged: “Some say Banks never saw a battle, as he was always running; but he did, he won this, which is well remembered,” wrote Mary scornfully.

27

—

The navy was also contributing its share of frustration and disappointment to Lincoln. On January 11, 1863, CSS

Alabama

attacked the U.S. blockade at Galveston, Texas. Once a forsaken collection of wooden buildings along a dreary sandbar that stretched for twenty-seven miles, Galveston had become a boomtown in recent years, sporting large modern warehouses and New Orleans–style mansions. Profits from shipping cotton—three-quarters of Texas’s produce passed through the seaport—had paid for colonnades of palm trees and lush oleanders to line streets that had formerly been mud tracks in the grass. The U.S. Navy had begun blockading Galveston in July 1861, and a Federal force had briefly held the port until Confederate general John Magruder (nicknamed “Prince John” by his enemies on account of his flashy behavior in front of ladies) recaptured the town on New Year’s Day 1863. Reinforcements to the naval blockade had just arrived when Captain Raphael Semmes and the

Alabama

cautiously approached the Union fleet.

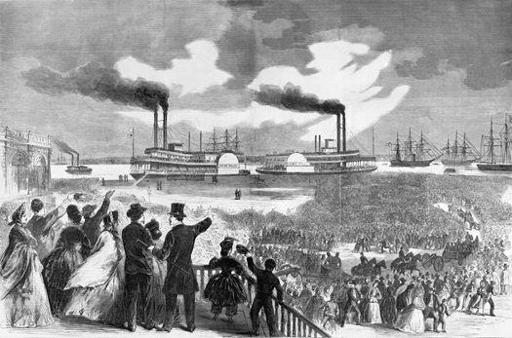

Ill.31

“Scene on the Levee at New Orleans on the Departure of the Paroled Rebel Prisoners,” February 1863.

In only six months the

Alabama

had become the most famous ship afloat. The entire English-speaking world knew her history, beginning with her audacious escape from under the noses of the British authorities. In addition to her aura of daring, she was beautiful to behold. The fifty-four-year-old Semmes had loved the

Alabama

from the moment he first saw her. During his thirty-seven years in the navy, he had never sailed on such a well-crafted vessel. “Her model was of the most perfect symmetry,” he wrote, “and she sat upon the water with the lightness and grace of a swan.”

28

The Confederate navy agent James Bulloch had asked Lairds to build him a ship that could survive the harshest of conditions for months on end. He knew that the

Alabama

would never have a home port or a regular source of supply.

29

The result was a 230-foot vessel with three masts, built for roving and raiding, capable of sail and steam power, equipped with two engines, a liftable screw propeller, and eight powerful guns. Her cabins could comfortably accommodate 24 officers and a crew of 120.

Semmes had been in command of CSS

Sumter

until the vessel required such extensive repairs that in the summer of 1862 he was forced to sell her in Gibraltar. When he and his second in command, Lieutenant John Kell, arrived in England, Bulloch realized that they were the obvious choice to take command of the

Alabama.

The new crew soon nicknamed their captain “Old Beeswax” on account of his highly waxed mustache. The sharpened tips—which looked both debonair and dangerous—were symbolic of the divergent nature of his character: Semmes was always perfectly correct and mild-mannered in his demeanor, but behind the mask was a stern and relentless fighter. He had strong literary and intellectual tastes, and, in contrast to many of his peers in the navy, he had no trouble adapting to home life when on furlough. During the long gaps between his deployments at sea, Semmes had established his own law practice. He was also a gifted writer, having published two well-received memoirs of his experiences during the Mexican War.

Despite frequent buffetings from rough weather and unruly sailors, Semmes soon imposed his will on the ship. The seamen were almost all British, “picked up, promiscuously,” wrote Semmes, “about the streets of Liverpool … they looked as little like the crew of a man-of-war, as one can well conceive. Still, there was some

physique

among these fellows, and soap, and water, and clean shirts would make a wonderful difference in appearance.”

30

The officers, on the other hand, were mostly Southerners, the notable exceptions being the master’s mate, twenty-one-year-old George Townley Fullam from Hull, and the assistant surgeon, David Herbert Llewellyn, a vicar’s son who had recently completed his residency at Charing Cross hospital.

31

Semmes considered the

Alabama

to be a ship of war rather than a privateer, and he demanded navy-style obedience from the men. “My code was like that of the Medes and Persians—it was never relaxed,” he wrote. “I had around me a staff of excellent officers, who always wore their side arms, and pistols, when on duty, and from this time onward we never had any trouble about keeping the most desperate and turbulent characters in subjection.”

32

The highest wages of any fleet and the promise of fantastic amounts of prize money also helped to maintain discipline.

The

Alabama

scored its first capture on September 5, an unarmed whaler, which was raided for supplies and then set afire. The merchant crew was allowed to go ashore in its whaleboats. Those men were lucky; other crews were held prisoner belowdecks until Semmes could unload them at a neutral port. By Christmas, the

Alabama

had successfully pounced on ten U.S. ships.

33

One capture often led to another, since Semmes would use the information gleaned from logbooks and timetables to chase after sister ships. But at Galveston, Semmes was offered a different opportunity—to prove to the world that the

Alabama

was capable of much more than merely preying on civilian ships. For the first time, she was meeting adversaries of her own class.

34

As soon as Semmes caught sight of the five blockading ships in front of Galveston, he ordered the

Alabama

to retreat slowly, hoping to entice one of the vessels into a chase. The Federal captain of the

Hatteras

took the bait, believing that he had caught a blockade runner in the act, and hardly noticed that Galveston was becoming smaller and smaller in the distance. “At length,” recounted Semmes, “when I judged that I had drawn the stranger out about 20 miles from his fleet, I furled my sails, beat to quarters, prepared my ship for action, and wheeled to meet him.”

35

The ships faced each other nose to nose, a mere hundred yards apart and yet only partially visible in the clear, moonless night. Using a bullhorn, the warship challenged first, ordering the unknown vessel to identify herself. Semmes cheekily shouted back, “This is her Britannic Majesty’s steamer

Petrel.

” There followed an awkward pause while the captain of the

Hatteras

pondered his next move. He had no wish to provoke the Royal Navy, but there was something suspicious about the ship floating before him. After some rapid calculation of consequences, he announced he was sending over a boarding party. Semmes called back that he was delighted, thus buying the

Alabama

a few precious minutes to load her guns. They heard orders being shouted and the creaking sound of a boat being lowered into the water. This was the signal for First Lieutenant Kell to cry out, “This is the Confederate States Steamer

Alabama

!” followed by a broadside from the cannons. The captain of the

Hatteras

quickly returned fire. Each time the

Alabama

landed a shell on her adversary, one of the sailors was heard to shout, “That’s from the ‘scum of England’!”

36

In less than fifteen minutes the

Hatteras

was completely disabled and starting to sink. The survivors from the warship were picked up and held in the brig until the

Alabama

docked at Port Royal in Jamaica on January 20.