A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (146 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

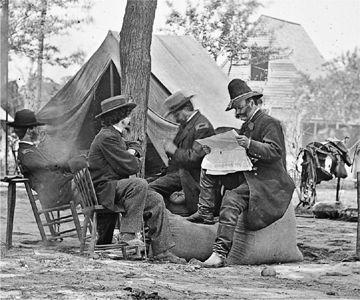

40.

Charles Francis Adams, Jr. (1835–1915) (second from the right), the only son of Charles Francis Adams to volunteer during the war, who rose from 1st lieutenant of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry in 1861 to colonel of the 5th Massachusetts (Colored) Cavalry in 1865 and led one of the first colored regiments through Richmond after its fall on April 3, 1865.

41.

Henry Adams (1838–1918). Henry accompanied his father, Charles Francis Adams, to London as his private secretary and later recorded his isolation and loneliness in The Education of Henry Adams. “Every young diplomat,” he wrote, “and most of the old ones, felt awkward in an English house from a certainty that they were not precisely wanted there, and a possibility that they might be told so.”

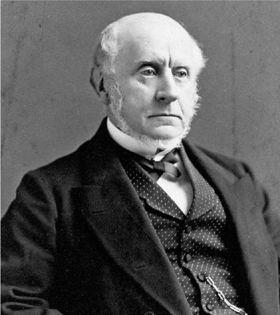

42.

Charles Francis Adams (1807–86), U.S. minister to Great Britain. Adams was the son and grandson of U.S. ministers and presidents. Though he was dutiful, honest, and hardworking, his family legacy cast a shadow over his entire life. “Charles Francis Adams naturally looked on all British [statesmen] as enemies,” wrote Henry Adams.

43.

Henry Feilden (1838–1921), British volunteer in the Confederate army. He was surprised to discover that he was not the only Englishman to offer his services to the South: “A good number have, prior to this, come out to this country,” he wrote in 1863, “and I believe have been obliged to serve as volunteers in the Army or on some General’s staff until they have proved themselves fit for something.”

44.

Francis Dawson (1840–89), British volunteer in the Confederate navy and subsequently the Confederate army. “My idea simply was to go to the South, do my duty there as well as I might, and return home to England.” In fact, Dawson stayed in the South after the war and became editor of the Charleston News and Courier.

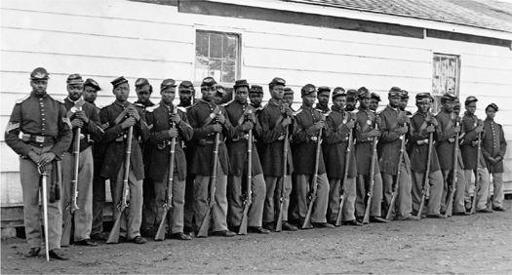

45.

A colored regiment poses for the camera. By the end of the war, there were more than 180,000 colored troops serving in the Union army. Their entry into the U.S. Army was slow and difficult and did not begin until Congress passed an act in July of 1862 that allowed them to enlist.

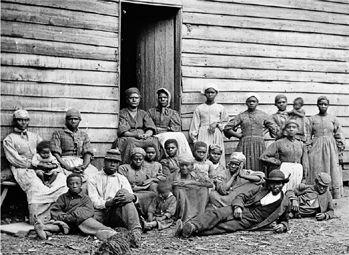

46.

Group of “contrabands,” Cumberland Landing, Virginia. Escaped slaves were not sent back to the South because they were classed as “contraband of war,” meaning they were part of the Southern war effort and were therefore liable for “confiscation.” Thousands of slaves from Virginia fled to shanty towns around the outskirts of Washington.

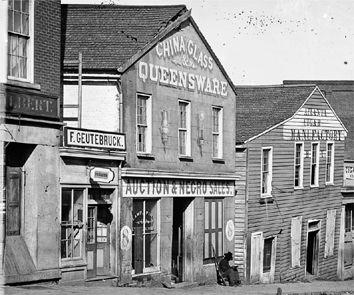

47.

A slave auction house in Atlanta, Georgia.

48.

The Rohrbach Bridge. During the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862, the bridge became known as Burnside’s Bridge after U.S. General Burnside ordered his men to cross it while being fired upon by the Confederates from the bluffs above the river.

49.

The dead after the slaughter at Antietam. The battle ended in a draw and was the single bloodiest day of the war. The two sides combined suffered more than 25,000 casualties.

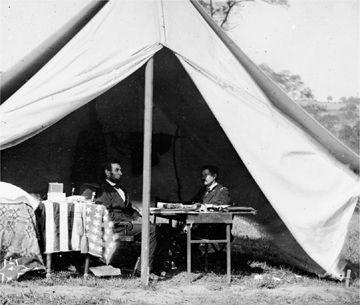

50.

President Lincoln and U.S. General McClellan meeting after the Battle of Antietam. Lincoln was furious with McClellan for not pursuing General Lee and crushing the Confederate army while it was in retreat.