A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (16 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Outraged by Seward’s effrontery, Newcastle did not mince his words in reply: “I then told him there was no fear of war except from a policy as he indicated, and that if he carried it out and touched our honor, he would, some fine morning, find he had embroiled his country in a disastrous conflict at the moment when he fancied he was bullying all before him.”

52

Seward never gave another thought to the conversation. With the election less than a month away, all his energy was directed toward the campaign in New York.

The royal party proceeded to Boston for more banquets, balls, and celebrations, and finally to Maine for one last hurrah. “During [Prince Edward’s] last day [in America] I was with the party & parted with him on the pier,” wrote Charles Sumner to his friend Evelyn Denison, speaker of the House of Commons. “At every station on the railway there was an immense crowd, headed by the local authorities, while our national flags were blended together. I remarked to Dr. Acland [the Radcliffe librarian at Oxford] that it seemed as if a young heir long absent was returning to take possession. ‘It is more than that,’ said he, affected almost to tears.”

53

Sumner believed that the two countries had arrived at a turning point in their relations. The prince was “carrying home an unwritten Treaty of Alliance and Amity between two great nations.”

54

A similar feeling was evident in England. After reading his New York correspondent’s reports, Mowbray Morris, the managing editor of

The Times,

wrote that the royal tour “will do a great deal of good here. It will convince persons who know nothing of Americans except by very bad specimens, that Brother Jonathan [the United States] really has brotherly feelings towards John Bull [Britain].”

55

It was only later, when Lyons could reflect on the tour from the comfort of his Washington drawing room, that he realized its “wonderful success.” “I have now had time to talk quietly about it with men whose opinion is worth having,” he wrote, “and also to compare newspapers of various shades of politics.”

56

He had seen nothing to make him wince, or even complain. During this period of political uncertainty, the American press had found in the ever-obliging Prince of Wales the one subject that did not stir controversy. Even the Anglophobic

New York Herald

announced “that henceforth the giant leaders of Liberty in the Old World and in the New are united in impulse and in aim for the perpetuation of Freedom and the elevation of man.”

57

But six weeks after the prince had sailed away to the strains of “God Save the Queen,” Lyons confided to the Duke of Newcastle that all their exertions might have been for naught. “It is difficult to believe that I am in the same country which appeared so prosperous, so contented, and one may say, so calm when we travelled through it,” he wrote. “The change is very great even since I wrote to you on the 29th October. Our friends are apparently going ahead on the road to ruin with their characteristic speed and energy.”

58

2.1

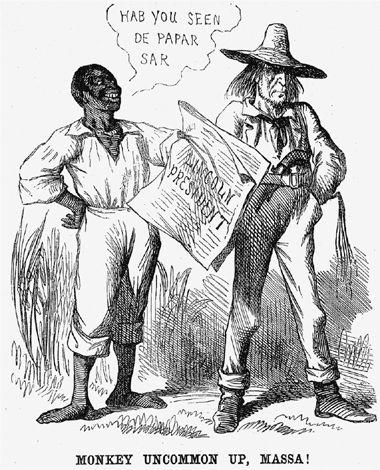

From the outset, Abraham Lincoln promoted himself as representing the middle ground. He believed that whites were superior to blacks, but that this did not give one human being the right to deprive another of his liberty. “As God made us separate, we can leave one another alone, and do one another much good thereby.”

2.2

The English were furious that U.S. sympathy for the Russians had extended to military aid, in the form of a steamship built for the Russian government by a private firm and revolvers supplied by Samuel Colt, as well as practical help from American doctors and engineers who volunteered their services.

3

2.3

According to a well-known anecdote, Russell was chatting to the Duchess of Inverness at a party one winter evening when he suddenly stood up, went over to the far corner, and began a conversation with the Duchess of Sutherland. A short time later, one of his friends asked him what on earth had happened. He had been sitting too close to the fire, Russell explained. “I hope,” the friend remarked, “that you told the Duchess of Inverness why you abandoned her.” After a pause he replied, “No, but I did tell the Duchess of Sutherland.”

2.4

Small quantities of Australian wine were on display at the Great Exhibition of 1851.

2.5

Lewis’s sardonic humor is best remembered in his quip “Life would be tolerable were it not for its amusements.”

2.6

On hearing the news that Gladstone had joined the government, Charles Sumner claimed, with his customary humility, that he had always known Mr. Gladstone would join the Liberals. “Mr. Gladstone’s fame seems constantly ascending,” he wrote to the Duchess of Argyll. “When I first met him at Clifton, at a time when he was out of office and much abused, I predicted what has taken place, though I hardly thought it would come so soon.”

12

2.7

Shortly after Seward departed, a report arrived from China that the U.S. Navy commodore in command of the American squadron had come to the aid of the Royal Navy during a fierce battle to capture the Taku forts in northeastern China. The U.S. commodore explained his decision to join the fight by declaring “blood is thicker than water.” This unexpected display of Anglo-American solidarity lent a rosy glow to Seward’s visit. If the traditional enmity between the two navies could be overcome, then anything was possible—even a friendly White House under a Republican administration.

2.8

John Adams and John Quincy Adams, the second and sixth presidents of the United States, also served as minister to the Court of St. James’s, from 1785 to 1788 and 1815 to 1817, respectively.

2.9

The biggest Anglo-American controversy in the early months of 1860 had been the bare-knuckle prizefight between the Englishman Tom Sayers and the American John Heenan on April 17. Billed as the world’s first international boxing contest, the match dragged on for thirty-seven rounds, until Heenan’s supporters broke into the ring. The contest was declared a draw, which led to the claim by furious supporters of Sayers that he had been robbed of his victory.

THREE

“The Cards

Are in Our Hands!”

Seven states secede—“Slaveownia”—Seward rises to the occasion—Bluster—Adams is offended—William Howard Russell at the White House—The April Fool’s Day memorandum—The Confederate cabinet—The fall of Fort Sumter—Lincoln declares a blockade—Southern confidence

“I

t seems impossible that the South can be mad enough to dissolve the Union,” Lyons wrote to the foreign secretary, Lord John Russell, after Lincoln was elected president on November 6, 1860. Yet South Carolina had already announced it would hold a special convention to decide whether to secede, and the news sent the price of shares tumbling on the New York Stock Exchange. The financial markets suffered another blow when a merchant vessel departed from Charleston, South Carolina, on November 17 with only the state flag flying from its mast. President Buchanan pleaded in vain with his proslavery cabinet to agree on a united response.

Lord Lyons cursed the little pig from San Juan Island and its penchant for Farmer Cutlar’s potatoes. He wished he had been able to settle San Juan’s boundary dispute during the Prince of Wales’s visit. With the secession crisis gathering momentum and Buchanan growing increasingly feeble in the face of his colleagues, he doubted that the issue could be resolved before Lincoln’s inauguration. Lyons suspected that the Republicans would be far less inclined than the Democrats to agree on a compromise. He had noticed that the Republican Party as a whole—not just Seward—tended to pander to anti-British sentiment as a way of showing that its abolition platform was independent of foreign opinion. It was important not to give the Republicans a reason to complain, Lyons wrote to Lord John Russell, and he suggested that the government refrain from making any public statements about the current political turmoil in America.

Lord John Russell received Lyons’s letter on December 18, the same day the South Carolina convention began its debate on the question of secession. The British cabinet had become increasingly concerned by the South’s reaction to Lincoln’s victory. Palmerston assumed it meant a second American Revolution was at hand. “There is no saying what attitude we may have to assume,” he wrote with concern to the Duke of Somerset, “not for the purpose of interfering in their quarrels, but to hold our own and to protect our Fellow subjects and their interests.”

1

Lyons’s insistence that Britain stand aloof seemed eminently sensible. “I quite agree with Lord John Russell and Lord Lyons,” Palmerston stated in a memorandum for the cabinet. “Nothing would be more inadvisable than for us to interfere in the Dispute.”

2

The law officers of the Crown assured Russell that the South Carolina ship flying its state flag could dock at Liverpool without any fuss. Customs officials there would treat the questionable flag as though it were a bit of holiday bunting, beneath anyone’s notice and certainly not a matter for official comment.

3

The imperative to stay out of America’s troubles was one of the few issues that united Palmerston’s fractious cabinet. The other was Giuseppe Garibaldi’s campaign to unite Italy. Here, too, the cabinet had agreed in July that the best course was to remain neutral and allow Garibaldi to fail or succeed on his own. Since setting out in the spring of 1860 to lead the Sicilian revolution against the Bourbon monarchy, Garibaldi had inspired hundreds of British volunteers to join his brigade. Dozens of officers had taken a leave of absence from the army in order to don the famous red shirt. Two ships from the navy’s Mediterranean squadron were almost emptied as sailors left en masse to form their own battery. Even the Duke of Somerset, Palmerston’s First Lord of the Admiralty, could not dissuade one of his own sons from running away to join the English battalion. The willingness of so many volunteers to help the Italians left the army and navy chiefs with little doubt that they would have a problem on their hands if war erupted in America, where both sides spoke English and the ties of friends and family were even stronger.

—

“We have the worst possible news from home,” the assistant secretary of the American legation, Benjamin Moran, wrote in his diary. A few days later he stood with the American minister, George Dallas, in front of a wall map of the United States, speculating with him as to which of the Southern states would go.

4

“The American Union is defunct,” pronounced Moran after the next diplomatic bag revealed that South Carolina had voted to secede on December 20, 1860.

Moran was relieved by the reaction of the British press to what it called the “cotton states.”

5

The Times

scoffed at the idea of secession: “South Carolina has as much right to secede from … the United States as Lancashire from England.”

6

But

The Economist

was less sympathetic, calling South Carolina’s secession poetic justice since Americans were always bragging about their perfect democracy. The

Illustrated London News

was the worst, in Moran’s opinion, since it asked “our American Cousins” to let the cotton states go in order to avoid making the same mistake as Austria, which had almost bankrupted itself resisting the Italians’ desire for independence.

7

Yet most newspapers followed the line of

The Times.

Words such as “sharp,” “ignoble,” and “unprincipled” were frequently used to describe South Carolina.

Punch

suggested that the seceding states could name their new country “Slaveownia.”

8