A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (15 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Seward was crushed. He had refrained from running for the presidency in 1856 on Thurlow Weed’s advice. Now he looked back and saw it as his squandered opportunity. His loss to Lincoln seemed inexplicable to anyone who had not attended the convention. “Seward went away from Washington a few days ago feeling perfectly certain of being named as the Candidate of the Republicans,” Lyons reported on May 22, 1860. “I never heard Lincoln even mentioned by the heads of the Party here.” Lyons could provide only scant details: “He is, I understand, a rough farmer who began life as a farm labourer and got on by a talent for stump speaking. Little more is known of him.”

39

Charles Sumner sent a letter of commiseration to Seward expressing his shock at the surprise result, although he wrote to the Duchess of Argyll “that, while in England, I always expressed a doubt whether Seward could be nominated.”

40

—

The British government was pondering the meaning of Seward’s defeat for Anglo-American relations when President Buchanan issued an invitation for the Prince of Wales to tour the United States.

2.9

The president had heard that Queen Victoria was sending the eighteen-year-old Prince Edward to Canada, in fulfillment of a long-standing request from the Canadians for a royal visit. Buchanan suggested that the prince’s trip could be extended by a further six weeks to include a stay at the White House.

Although the Queen was initially doubtful whether her son was up to the job, Prince Albert and the cabinet realized that Britain had been presented with a rare opportunity to improve the transatlantic relationship. Lyons, who was awarded the daunting task of deciding the prince’s itinerary, was delighted to have something other than the island of San Juan to discuss with Buchanan. Together with the Queen and the Foreign Office, Lyons devised an arrangement whereby the prince would travel to the United States in an unofficial capacity, as if on holiday, though accompanied by himself and the Duke of Newcastle at all times. There were to be no official deputations, delegations, or ceremonies. This, Lyons hoped, would dampen any attempts by Irish agitators to whip up local Anglophobia. Furthermore, in a nod to republican sentiment, the prince would use the least of all his titles, Baron Renfrew, allowing him to be treated as an ordinary British subject while “incognito.” Except for a passing visit to Virginia, Lyons simply left the South off the prince’s itinerary.

Naturally, in all the cities on the prince’s route, the request for “Baron Renfrew” to be treated as a private citizen was ignored. Almost every inhabitant of Detroit was at the docks when the royal party clambered off the ferry

Windsor

on September 20, 1860. The same was true at the train station in Chicago. “Bertie,” as his family called him, was taken aback by the enthusiasm that greeted his arrival. The Americans seemed to like him even more than the Canadians did. At his every stop there were parades, fireworks, banquets, triumphant tours, and thousands upon thousands of cheering spectators. For a young man who was used to being treated as a great disappointment by his parents, this was an experience beyond fantasy.

By the time the royal entourage arrived at Washington in early October, Bertie had become an enthusiastic admirer of America; he even thought the unfinished capital was a fine place to visit. He spent a night at the White House, where President Buchanan and his niece, Miss Harriet Lane, made an exception for the young prince by allowing card games after dinner (although no dancing).

41

After being shown Congress, the Washington Monument, the Treasury, and a score of other public buildings, he informed his parents, “We might easily take some hints for our own buildings, which are so very bad.”

42

From Washington, Lyons accompanied Prince Edward to Mount Vernon, George Washington’s estate on the banks of the Potomac River, sixteen miles from Washington, where the prince planted a tree at Washington’s tomb. The British minister was just beginning to congratulate himself upon a splendid piece of organization when the visit threatened to unravel during the trip to Richmond, Virginia. The locals were furious because the prince’s hosts had canceled a large slave auction, and a hostile crowd gathered outside his hotel. Lyons managed to avoid a public confrontation, but that afternoon, he and Newcastle encountered a second embarrassment when they discovered en route that the royal party was being taken to visit a slave plantation. Only with great difficulty did they convince their hosts that a tour of the mayor’s office would be much more pleasurable.

43

When “Baron Renfrew” arrived in New York on October 11, his guardians were beginning to fear that the good-natured prince’s appetite for orphanages and parades had run its course. But Bertie absolutely loved New York. Some 300,000 people (out of a population of 800,000) lined the streets, climbing on rooftops, trees, and carriages, even hanging from streetlamps, to watch his carriage proceed up Broadway to his hotel. They cheered, threw flowers, and waved placards that said “Welcome, Victoria’s Royal Son.” “I never dreamed we would be received as we were,” he wrote.

44

The prince had never imagined such comforts, either. The Fifth Avenue Hotel was the newest and grandest addition to New York’s already magnificent accommodations. Completed in 1859 on the “edge” of town at Twenty-fourth Street and Madison Square, the marble-clad six-story building had the latest conveniences including en suite bathrooms, communication tubes that allowed a guest to speak his request to room service, central heating, and, most exciting of all, a “perpendicular railway intersecting each floor.” The American ideal of luxury was different from the European. The ornaments and objets d’art often taken for granted in English or French houses were missing, but “the rooms are so light and lofty; the passages are so well warmed; the doors slide backward in their grooves so easily and yet so tightly; the chairs are so luxurious; the beds are so elastic, and the linen so clean, and, let me add, the living so excellent,” he wrote, “that I would never wish for better quarters.… All the domestic arrangements (to use a fine word for gas, hot water, and other comforts) are wonderfully perfect.”

45

For one night the prince was allowed to sample life as it was lived by New York’s gilded “Four Hundred.” On October 12, 1860, the entire entourage, including Lyons, traveled in a parade of open carriages to a grand ball at the Academy of Music on Fourteenth Street organized by New York’s most distinguished citizen, Peter Cooper. Four thousand guests bribed, blackmailed, or otherwise insinuated their way into the most coveted social event of the decade. The danger that the prince would inadvertently start a stampede was so great that the entrances to the supper rooms were guarded by prominent citizens, who admitted fifty guests at a time.

46

Even so, the ballroom floor partially collapsed beneath the dancers’ weight and carpenters had to be called in during dinner. Bertie danced until five in the morning. Four hours later, he was dressed and dutifully touring P. T. Barnum’s American Museum, where he saw the “Feejee Mermaid” and shook hands with Tom Thumb.

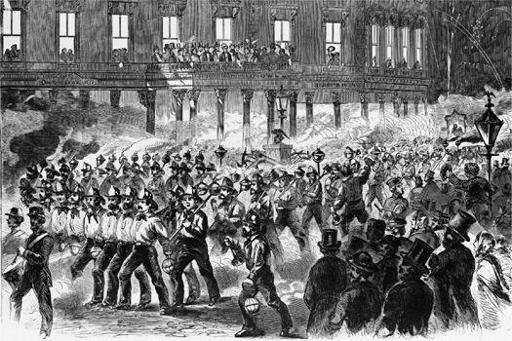

Ill.4

Grand torchlight parade of the New York firemen in honor of the Prince of Wales, passing the Fifth Avenue Hotel, October 13, 1860.

That night, five thousand men from the City Fire Brigade marched in a torchlight procession past his hotel. Each company let off fireworks as it went under the prince’s balcony. “This is all for me! All for me!” he exclaimed.

47

He was exhausted, like the rest of his entourage, but also elated. The warmth of the American reception made it difficult to imagine that there had ever been open hostility between the two countries. Even the much-anticipated protests from Irish immigrants had been confined to a single incident, when the Irish-dominated 69th Regiment of the New York State Militia refused to march in the parade up Broadway.

48

Leaving New York with great regret, the prince traveled to Albany on October 15, 1860, for a grand dinner given by the governor of the state, Edwin Morgan.

Seward also attended Morgan’s dinner. The past few months had been turbulent for him. His return to Washington following the Republican convention was one of the most humiliating episodes of his life. He told his wife that the house felt “sad and mournful” and that he missed the Napiers, whose engravings on the wall seemed “like pictures of the dead.”

49

Seward could not decide which was worse, the complacent sympathy of Sumner or the exaggerated politeness of Mason and the other Senate Democrats.

50

The demeanor of both demonstrated that they considered his political career effectively at an end. Only the Adamses, wrote Seward, were as “generous, kind, faithful as ever.” Adams took him to task with uncharacteristic force after he learned that Seward was contemplating his retirement from politics. Neither Adams nor Weed thought Lincoln capable of winning the election without Seward, let alone running the country. Thurlow Weed had met with Lincoln after the convention and offered his services for the upcoming campaign. His conversation had convinced him that if Lincoln were elected, which was beginning to look quite possible, the newcomer would never be a match for Seward. Lincoln might be president in name, but the real power would reside with Seward.

Weed’s optimism about Seward’s role stemmed from the Democrats’ recent split into two camps. The Northern and Southern factions had decided to field their own candidates, Stephen Douglas for the North and John Breckinridge for the South, almost guaranteeing the defeat of both in favor of the Republicans. By early August, Weed had managed to drag Seward out of his despondency and into a sufficiently robust frame of mind to contemplate a tour through Northern and western states on Lincoln’s behalf. Seward had to put up a brave front and conduct himself as a loyal party man; any other action would have given Lincoln an excuse to leave him out of his cabinet. Seward knew that Weed was right, but his wisdom did not make the effort any less painful.

51

The Republican message that Seward carried to the Northern states contained something for everyone: no expansion of slavery, a protective tariff for American industries, a homestead law giving away undeveloped federal land, and government aid to construct a transcontinental railroad.

Seward decided that he could not face the next leg of his tour unless he had sufficient company to keep him distracted. He set off in September with a large retinue that included a reluctant but loyal Adams and his twenty-five-year-old son, Charles Francis Jr.; the president of the New York City police board, General James Nye (and Nye’s daughter); his biographer George Baker; and his daughter, Fanny. But even surrounded by friends and family, Seward had to wrestle with his emotions. The signs of his inner struggle were evident in the copious cigars and glasses of brandy that he consumed during the long train journeys. Charles Francis Jr. never saw Seward visibly drunk, but he was sometimes sufficiently inebriated to lose control “and set his tongue going with dangerous volubility.” Throughout the northwestern states, thousands of people flocked to hear Seward speak. The public adulation heightened Seward’s already febrile emotions; his speeches became coarser and more strident. In Michigan on September 4, he marred a strong antislavery speech with racist asides about the feebleness of the African race. In Minnesota on September 22, he declared that Canada was destined to become part of the United States.

Seward no doubt believed that it was more important to reach out to undecided voters with his populist message than to concern himself about the effect of his pronouncements in far-off places. The Prince of Wales’s tour of Canada was in midswing when Seward made his speech about its future as a United States territory. The unfortunate timing prompted the Canadian and British press to give his speech much greater attention and credence than it merited. When he sauntered into Governor Morgan’s house on the night of the dinner for the prince, Seward was apparently unaware of the huge offense he had caused. The occasion was already a difficult one for Seward; he had often discussed the idea of a royal visit with Lord Napier, but Seward had avoided the British legation after Napier’s departure, and barely knew Lyons. He felt more comfortable talking to the Duke of Newcastle, who gratifyingly remembered him from his visit to England. Seward started well, until the same urge to drink and talk crept over him. By the end of the meal, the duke was reeling from the encounter. “He fairly told me he should make use of insults to England to secure his own position in the States, and that I must not suppose he meant war. On the contrary he did not wish war with England and he was confident we should never go to war with the States—we dared not and could not afford it,” the duke reported later to the governor-general of Canada.