A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (21 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Benjamin Moran thought Dallas’s benign view of the British made him either an idiot or a crypto–Southern sympathizer. Dallas was certainly neither, but the knowledge that he was soon to go home may have made him apathetic when he should have been wooing potential Northern allies in Parliament. Moran also knew of at least one MP who was collaborating with the nascent Southern lobby in England. William Gregory, the MP for Galway, had given notice in the House of Commons that he was going to propose recognition of the South on May 1. Moran thought the move had been prompted by Gregory’s friend Robert Campbell, the American consul in London.

4.1

Campbell was a genial though strident secessionist from North Carolina who had supplied Gregory with letters of introduction for his tour of the United States in 1859. In Washington, he had stayed in a boardinghouse popular with Southern senators; their “fire-eating talk” of independence, interspersed with liberal amounts of whiskey, had swept the MP into their ranks. Privately, he thought their humanity had been dulled by slavery, but Gregory accepted his new friends’ claim that emancipation was morally and economically impossible.

5

Moran was furious with Dallas for failing to curb the pro-Southern activities of consuls who had not yet been replaced by Republican appointees, but he dared not speak when his own future seemed so uncertain. He remained in suspense until confirmation of his reappointment arrived on the fifteenth. Moran’s other fear—that he was the only loyal American official left in Britain—seemed a raging certainty after he caught one of the new Southern envoys, Ambrose Dudley Mann, sneaking into the legation to see Dallas.

The arrival of the Confederate envoys was not unexpected; their identities had been public knowledge for several weeks. Consul Robert Bunch wrote from Charleston to warn the foreign office that they were three of the rankest amateurs ever to have been sent on so sensitive a diplomatic mission. He attributed President Davis’s selection of such men to Southern arrogance and the belief that the Confederacy did not need proper advocates when cotton could do the talking. Mann had served as a U.S. minister to Switzerland but Bunch dismissed him as “a mere trading politician, possessing no originality of mind and no special merit of any description.” The second envoy, William Lowndes Yancey, had never been anything but a rabble-rouser. His campaign to reopen the slave trade, not to mention his support for expeditions against British territories in Central America, made him a peculiar choice to send to England. Bunch was particularly disdainful of Yancey: “He is impulsive, erratic and hot-headed; a rabid secessionist.” Bunch could not see a single reason for the appointment of the third envoy, Pierre Rost, apart from his friendship with Jefferson Davis’s family and his proficiency in Creole French.

6

Moran despised Dallas’s excuse that Mann was an old and valued friend until he, too, was forced to choose between loyalty and patriotism. A few days after Dudley Mann visited the legation, Moran received a letter from a friend in London who asked him for the Confederate envoy’s address. The friend, Edwin De Leon, until recently the U.S. consul in Egypt, had invited him to his wedding two years earlier, but Moran was appalled at his request and wrote sorrowfully that “I would do anything in reason for him, but could not find it in my conscience to assist treason.”

7

—

Forcing a debate in the House of Commons had become William Gregory’s mission, and he would not be thwarted. Palmerston pulled the pro-Confederate MP aside in the Commons on April 26 and demanded to know why he saw fit to place the government in such an awkward position. He reminded Gregory that the speeches would be reprinted in Southern and Northern newspapers and that both sides would end up being “offended by what is said against them, and will care but little for what is said for them; and that all Americans will say that the British Parliament has no business to meddle with American affairs.” He reported to Lord John Russell that Gregory “admitted the truth of much I said, but said he had pledged himself to Mr. Mann, the Southern envoy.… Perhaps your talking to Gregory, either privately or in the House, might induce him to put his motion off.”

8

Russell was anxious about being pushed to make a public statement ahead of events. George Dallas had shown that he was as ignorant of the situation as the Foreign Office. During his last interview with Russell on May 1, he had insisted that a blockade was not under consideration, since there was no mention of the fact in the latest State Department instructions; it had to be a fabrication of the New York press. But Russell discovered the next day from Lord Lyons’s dispatches that the idea was very much under consideration.

The day after Palmerston’s confrontation with Gregory, the British government learned that the Confederates had captured Fort Sumter. The initial newspaper reports were brief, but it appeared as though the South had won an easy victory. (The Thompson family in Belfast became the envy of the neighborhood after they received a long account of the battle from their son, a Union private in the Sumter garrison.)

9

“We cut a sorry enough figure indeed,” complained Moran as he read through the dailies. “Everybody is laughing at us.” Many papers described the news as “a calamity” and “a subject of regret, and indeed of grief,” but Moran’s attention was held by the

Illustrated London News,

which printed a pious editorial in favor of peace and “no coercive measures,” next to an announcement that Frank Vizetelly, the paper’s star artist, war reporter, and brother of the editor, was taking the next steamer to New York.

10

The tutting and clucking in the British press about the demise of the democratic experiment and the sorry state of “our American cousins” also grated on Moran’s nerves.

The Economist

recalled Britain’s futile reaction to the American Declaration of Independence and advised the North to settle the dispute with grace; to continue fighting now, its editor, Walter Bagehot, scolded, would be “vindictive, bloody and fruitless.”

11

The conservative

Saturday Review

could not resist making a dig at Seward, who, “though he cannot keep the Federal fort at Charleston, has several times announced his intention of annexing Canada.”

12

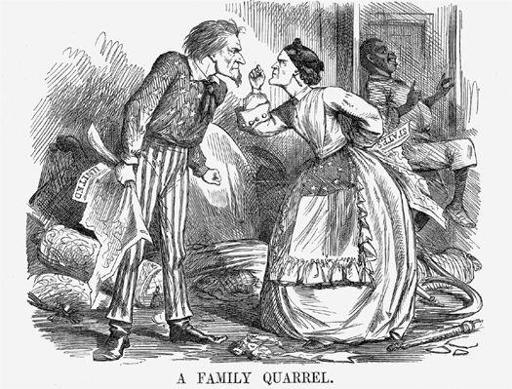

Ill.6

Punch depicts the North and South as a mismatched couple.

Lord John Russell had still not spoken to William Gregory when the Southern commissioners Yancey and Rost finally reached London on April 29, a week after Mann. Unaccustomed to foreign travel, they had passed two miserable days in Southampton and had arrived in the capital feeling bewildered and frightened. Rather than pausing for a moment to consider the best way of contacting the Confederate community, they sent a telegram to the American legation addressed to Ambrose Dudley Mann. “The unblushing impudence of these scoundrels,” ranted Moran, “to send their message to the US Legation for one of their fellow traitors.”

13

The timing and announcement of their arrival was fortunate for Lord John Russell, since it gave him a bargaining chip with Gregory, who agreed to postpone his motion to June 7 in return for a Foreign Office meeting with the Southerners on May 3.

Russell was not making a great concession, since it was standard Foreign Office practice to receive representatives from breakaway countries. These meetings never carried official weight, nor were the emissaries accorded diplomatic rank. Russell assumed that Dallas had lived in England long enough to know this, and that Charles Francis Adams could have it explained to him when he eventually arrived. Russell was disturbed by the thought of Confederate privateers roaming the seas, and, at his request, the Admiralty was already taking precautionary measures to reinforce the North Atlantic squadron. The prospect of encountering lawless privateers so frightened Dallas that he booked passage for his wife and three daughters for May 1, hoping they would be home before transatlantic travel became impossible.

Russell’s satisfaction over his dealings with Gregory lasted only twenty-four hours. On May 2 he received a run of telegrams: the first announced that Lincoln had decided on a blockade rather than port closures; the next, that Virginia, that mainstay of the American Revolution, had seceded, depriving the North of the large weapons arsenal at Harpers Ferry; and finally, that Maryland had erupted in violence, leaving eleven people dead in Baltimore during street fighting between Federal troops and Southern protesters.

4.2

“This is the first bloodshed and God knows where it will end,” Moran wrote in his diary. It surprised and comforted him when several Englishmen called at the legation vainly asking to join the Federal army. But the reaction of Russell’s predecessor at the Foreign Office, Lord Clarendon, showed that old resentments had a habit of reviving: “For my own part if we could be sure of getting raw cotton from them, I should not care how many Northerners were clawed at by the Southerners & vice versa!”

14

When Russell went to the House of Commons that evening, he was bombarded with questions from MPs, not a few of whom shared Clarendon’s view. He could give little enlightenment, but to those who expressed a desire for British intervention he warned against such a reckless move. “Nothing but the imperative duty of protecting British interests, in case they should be attacked, justified the government in at all interfering,” he told the House. “We have not been involved in any way in that contest. For God’s sake, let us if possible keep out of it.”

15

He delivered a similar message to the Southern envoys when they arrived for their interview on Friday, May 3. Gregory had warned them about Russell’s notorious shyness, but they had not expected the frigid politeness with which they were received. Russell caught them off guard by declaring he had “little to say.” William Yancey stumbled through a speech about the Constitution, liberty, and states’ rights. He insisted the slave trade would not be revived, which Russell disbelieved, threw in a warning about cotton, which Russell ignored, and finally asked for immediate recognition, which Russell refused. The envoys returned to their lodgings at 40 Albemarle Street thoroughly disheartened.

Lord John Russell spent the weekend of the fourth and fifth of May carefully analyzing the choices open to the British government. He hoped that antislavery would become the overriding cause of the war, but feared that the North would throw it over without hesitation if the Union could thus be saved. He was also torn between despising the South for its dependence on slavery and admiring its spirited bid for independence. Above all, he agreed with Lord Lyons that to give preferential treatment to the North would be unwise and possibly dangerous with Seward at the helm. Accepting the legality of the blockade, which would require a declaration of official neutrality, struck him as the wisest course, he told his colleagues, especially in light of Seward’s evident keenness to manufacture a reason for declaring war.

The cabinet was not enthusiastic about adopting a policy that was so dangerous to the country’s cotton industry. Palmerston agreed with the proposal, though he felt it was a heavy price for staying out of the conflict. “The South fight for independence; what do the North fight for,” asked the home secretary, Sir George Cornewall Lewis, “except to gratify passion or pride?”

16

William Gladstone was privately even more outspoken for the South and compared Jefferson Davis to General Garibaldi. When his friend Harriet, Duchess of Sutherland, heard about his views, she was outraged and demanded to know how he could “think the Southern states most in the right—I did not hear you say; I don’t believe it.”

17

Nor did she accept his explanation that the wishes of minorities ought to be respected.

18

Only the Duke of Argyll, her favorite son-in-law, wholeheartedly supported Russell. He abhorred revolutionary movements on principle; moreover, his friendship with Charles Sumner had given him an insight into American politics. He rightly understood that the Union had to be safeguarded since the South would never abolish slavery on its own.

In declaring neutrality, Russell was convinced he had chosen the best alternative; he had consulted the law officers of the Crown, as he always did when in doubt, and in their opinion the crisis in America was not a minor insurgency but a genuine state of war. The blockade could and should be recognized, they told him, and so should the right of the South to employ privateers. Russell endured some aggressive questioning in Parliament when he announced the government’s decision on May 6. He was also pressured by Gregory into seeing the Confederate envoys for a second time, on the grounds that the Northern blockade had not been confirmed at the first meeting. Russell suspected they would try to make more of the neutrality announcement than the government intended. Their exultant demeanor on May 9 showed that his instincts had been correct.

19

The envoys were unaware, however, that even as they pressed their arguments on him, the law officers were composing an additional proviso to Britain’s declaration of neutrality that would make it illegal for a British subject to volunteer for either side in the war. Russell had meant it when he said “for God’s sake, let us if possible keep out of it.”