A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (26 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

“There is a British Regiment gotten up here,” one English immigrant, Edward Best, told his aunt Sophie in Somerset. “It seems to be very popular and I trust will carry its flag through this affair with credit to our dear old country.”

35

Consul Archibald, however, was embarrassed when the recruiters for the British Volunteers opened their office in the same building as the consulate.

36

He sent a letter to the main newspapers denying any involvement, though this provoked the press to label him a Southern sympathizer.

The British Volunteers started off well and could be seen training each morning in the drill room at the Astor Riding School.

37

But the regiment soon became a magnet for anti-British hostility, as did a regiment in Massachusetts that called itself the British Rifle Club.

38

“It is not right that British residents should be taunted and twitted without cause,” complained the

Albion,

a weekly journal for the British community in New York.

39

The British Volunteers lost its appeal to recruits after one of the captains was accused of being a Confederate agent, a charge that was repeated in the press even after the unfortunate captain was exonerated.

By mid-June the British Volunteers’ difficulties became insurmountable and they merged with an Irish regiment to become the 36th New York Volunteers. There were frequent fights and stabbings in the new outfit between the English and Irish factions, and mealtimes could be explosive. The violence encouraged many of the former British volunteers to join the 79th New York Highlanders, which in contrast to the Irish 69th had provided the Prince of Wales’s honor guard during his visit in 1860. It was safe to be called Scots, Irish, or Welsh, but not British or English, noted Mr. Archibald.

A young Englishman named Ebenezer Wells had joined the 79th Highlanders when he arrived in New York in 1860 in order to have something to do on the weekends. “When the Civil War broke out, the regiment volunteered for the war,” he wrote in his memoirs. “I was buglar [

sic

] and being away from parental restraint thought it would be a splendid excursion.”

40

The men were thrilled when they received their orders in early June. “It was a beautiful Sunday when we marched down Broadway amidst deafening applause,” wrote Wells. The crowds adored their tartan uniform, especially the officers’ kilts. Nothing about the occasion hinted at the hardships ahead. Their knapsacks were packed with every conceivable delicacy as though they were on a Sunday outing. But, Wells added ruefully, if they had known what lay in store for them, “how depressed instead of elated would our spirits have been.”

41

Ebenezer Wells experienced his first brush with violence as the regiment passed through Baltimore. He was ambushed by a stone-throwing mob and lost his cap and blanket before being rescued by members of his company. The 79th Highlanders were tired and hungry when they finally reached Washington on June 4. The sweltering city had become a vast military camp. Rows of white tents and parked artillery occupied the green fields around the half-finished Capitol building. Long trains of covered wagons filled the dusty thoroughfares.

42

At night, the city resonated with wild shouts and hoots, and thunderous fireworks were answered with rounds of gunfire.

The Highlanders were allocated temporary quarters at Georgetown University. The 69th had only recently vacated the premises, and their detritus still littered the grounds. The campus was eerily silent, all but fifty of the student body having volunteered to fight for the South. The men were nervous. The Confederate army, under the command of the hero of Fort Sumter, General Beauregard, was only seventeen miles to the west. “We lay every night with our muskets by our sides, ready cocked, and one finger on the trigger,” wrote one of the recruits from the old British Volunteers. “It is a tough life, I can tell you.”

43

His sentiment was widely shared in camps around the city. No regiment was so experienced or so confident that its men did not live in fear of an ambush or a surprise raid. The roar of the bullfrog, the screech of the night owl, “every rustle of the wind among the trees,” wrote the newly arrived war reporter and artist Frank Vizetelly, “every sound that breaks the stillness of the night, is taken for the advance of the Secessionists.”

44

Vizetelly had accompanied the 2nd New York Regiment to their camp on the border between Washington and Virginia. The sounds of the forest did not frighten him; the thirty-year-old Vizetelly had spent the past ten years in the midst of battles and revolutions all over Europe. He had never known any other life than journalism. His father and grandfather were both well-known printers and engravers on Fleet Street. His three brothers were also in the trade; Henry, the second oldest, was one of the founders of the

Illustrated London News,

which was the first weekly newspaper to illustrate its articles with eyewitness drawings.

Vizetelly’s fame in England rested on his pictures of Garibaldi’s Sicily campaign. Dispatched by Henry to provide sketches of the fighting for the

Illustrated London News,

Frank soon abandoned any pretense of objectivity and allied himself with Garibaldi. It was not in his nature to be impartial: his drawings were not only skillful depictions of a moment or tableau but moving narratives that engaged the emotions of the viewer. His images demanded a reaction, not unlike Vizetelly himself, whose craving to be the center of attention was insatiable. “He was a big, florid, red-bearded Bohemian,” recalled an admirer, “who could and would do anything to entertain a circle.”

45

Whether sitting around a campfire or dining in an officers’ mess, Vizetelly would transfix his listeners with vivid stories, replete with voices and accents, or lead them in boisterous sing-alongs that lasted until the small hours.

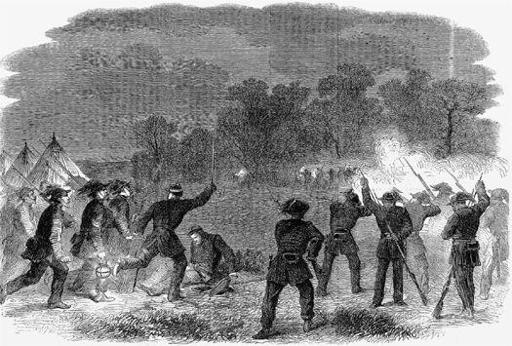

Ill.7

Attack on the pickets of the Garibaldi Guard on the banks of the Potomac, by Frank Vizetelly.

William Howard Russell envied Vizetelly in just one respect: he was unmarried and could travel wherever he pleased without upsetting his family. Otherwise he pitied him. Vizetelly constantly teetered between depression and mania, and when not distracted by the thrill of danger, he became self-destructive and reckless. Vizetelly partially understood his limitations and chose to live rough with the 2nd New York Volunteers, even though the camp was infested with rattlesnakes and “myriads of bloodthirsty mosquitoes,” rather than lounge in the saloon at Willard’s.

46

Sometimes he visited the camp of the Garibaldi Guard to swap stories with the handful of genuine veterans in the regiment. (The colonel there was a Hungarian con man, and most of the volunteers were not Italian but adventurers from the four corners of the globe.) On one of the few occasions Vizetelly did go to the capital, he received an invitation to dinner from Seward. He arrived expecting to regale his host with stories about the American volunteers he had encountered among Garibaldi’s Red Shirts, but Seward was interested only in the tenor of his sympathies and whether he was planning to visit the South like that villain William Howard Russell. “I disclaimed any idea of so doing,” reported Vizetelly.

47

Once Seward took against a person, it was rare for him to change his mind. Russell had sensed at their first meeting that he could be a dangerous enemy. During his return journey from the South, Russell had read enough of the Northern press to warn him of the reception awaiting him in Washington. But “I can’t help it,” he wrote on June 22 to his fellow

Times

correspondent in New York, J. C. Bancroft Davis; “I must write as I feel and see.… I would not retract a line or a word of my first letters.” He hoped that Northern newspapers would reprint his

Times

reports from the South, which would show that he was not a rebel sympathizer.

48

Russell arrived in Washington on July 3, 1861. This time he stayed away from Willard’s and found lodgings in a private house on Pennsylvania Avenue. He regretted the decision as soon as he unlocked the door to his room and caught the stench of the privy beneath the window. Once he had changed his clothes, Russell called on Lord Lyons to give him a report on the South, glad for the excuse to escape his lodgings, if only for a few hours. The legation was almost as dark as his bedroom, since Lyons had ordered the gas lamps to be kept unlit in order to avoid adding unnecessary heat. “I was sorry to observe he looked rather careworn and pale,” Russell wrote afterward.

49

One of the attachés whispered to Russell as he was leaving that “the condition of things with Lord Lyons and Seward had been very bad, so much so Lord L would not go near State Dept. for fear of being insulted by the tone and manner of little S.”

50

Ever since the neutrality proclamation had become known, Seward had been threatening and plotting to force a reversal of the South’s belligerent status. Lyons was constantly on the watch against Seward’s stratagems to weaken Britain’s leadership and Mercier’s attempts to sabotage the blockade. Try as he might, Lyons could not make Seward understand that Europe was only respecting the blockade out of deference to Britain. Russell returned to his lodgings feeling depressed by Seward’s misguided behavior toward Lord Lyons. There was no other foreign minister in Washington, Russell wrote in his diary, “who watches with so much interest the march of events as Lord Lyons, or who feels as much sympathy, perhaps, in the Federal Government.”

51

“Sumner makes it appear he saved the whole concern from going smash,” Russell wrote after he bumped into him on the street and had to stand for an hour in the blistering heat while Sumner gleefully enlarged on “the dirty little mountebankism of my weeny friend in office.”

52

Russell was not sure whether to believe him until he called on Seward the following day and was subjected to another of his tirades. The secretary of state informed Russell that if he wished to go anywhere near the army, his passport would have to be countersigned by Lord Lyons, himself, and General-in-Chief Winfield Scott. He ended the interview with a lecture on the impropriety of Britain’s granting belligerent status to the Confederates: “If any European Power provokes a war, we shall not shrink from it. A contest between Great Britain and the United States would wrap the world in fire, and at the end it would not be the United States which would have to lament the results of the conflict.” Russell tried to appear serene during this outburst, but as he listened to Seward’s monologue he could not help seeing the funny side. There they were “in his modest little room within the sound of the evening’s guns, in a capital menaced by [Confederate] forces,” and yet Seward was threatening “war with a Power which could have blotted out the paper blockade of the Southern forts and coast in a few hours.”

53

“Seward is losing ground in Washington and New York very fast,” Charles Francis Adams, Jr., reported to his father on July 2. “Sumner has been here fiercely denouncing him for designing, as he asserts, to force the country into a foreign war.”

54

It was true that Seward had not calculated on Sumner’s relentless plotting against him, or that Sumner would try to set himself up as a rival secretary of state from the Senate; but both William Howard Russell and Charles Francis Jr. had been misled by Sumner. Far from being humiliated, Seward was reemerging in triumphant form, as the crush at his parties attested. June had been a month of consolidation and reconciliation between the president and his wayward secretary; Lincoln had won Seward’s support through a combination of firmness and magnanimity in victory. Displaying more statesmanship than his detractors would admit, Seward recognized that Lincoln possessed the skills required in a president, “but he needs constant and assiduous cooperation.”

55

The alteration in Seward’s attitude toward Lincoln was accompanied by a realization that neither bribery nor the lure of fighting Britain would make the Southern states return to the Union. The change in Seward could be discerned in early July after Gideon Welles engineered a bill through Congress that gave Lincoln the authority to close Southern ports by decree. The foreign ministers in Washington warned Seward that Europe would ignore any attempt by the North to impose legal restrictions on ports it did not physically control. If he genuinely sought a foreign war, all Seward had to do was demand compliance with these fictitious port closures, and the Great Powers would revolt. Seward believed them and persuaded Lincoln to say nothing publicly about the bill.