A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (79 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

Hooker knew that the Army of the Potomac had a two-to-one advantage over Lee, whose Army of Northern Virginia numbered fewer than 65,000 men. The Union general thought he could increase the odds even more by sending his 12,000-strong cavalry corps on raids around Richmond, with instructions to “Let your watchword be fight, fight, fight.” He wanted the cavalry to isolate Richmond from the rest of the state, causing panic in the capital and, with luck, forcing Lee to detach a part of his army for its defense. Sir Percy Wyndham’s regiment had a merry time ripping up railroads and cutting communications north of Richmond, rarely encountering opposition. Predictably, Wyndham went too far and began thinking up his own assignments, which led to his arrest for insubordination; after vigorous protests by his supporters, he was released with a censure for disobeying orders.

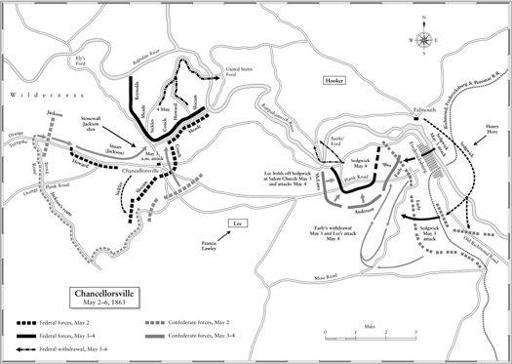

Hooker was in a jubilant mood once the Army of the Potomac started moving on April 29. Leaving 40,000 troops at Fredericksburg, under the capable command of General “Uncle John” Sedgwick, he ordered the rest, numbering almost 80,000 men and officers, to cross the Rappahannock River at two different places and rendezvous at Chancellorsville, nine miles west of Fredericksburg. The name applied not to a village but to a clearing in a wood that spread over seventy square miles in such dense thickets that locals simply labeled it “the Wilderness.” A crossroads cut through the middle of the clearing, passing close to the veranda of an old brick mansion named Chancellor House. Here Hooker and his staff set up their temporary headquarters, flushing the indignant female inhabitants out of the parlor to their bedrooms on the floor above. He was ready to launch his surprise attack. “My plans are perfect,” he declared on the eve of the battle; “may God have mercy on General Lee, for I will have none.”

22

19.1

Stanton was like Seward in his inability to resist an aristocratic title. He granted a visitor’s permit to Lord Abinger, who was stationed in Canada with the Scots Guards. Abinger went down to the Army of the Potomac, was treated to a grand review, and had his photograph taken with Hooker’s staff. Owing to his discreet and affable nature, no one among his hosts had the faintest idea of his true feelings. In contrast to the neutral Crowther, Abinger was thoroughly sympathetic to the South. The previous April, he had invited Commissioner James Mason to dine at the regimental mess in Eastbourne. Mason was most gratified to have the notice of a Scottish peer and recorded every detail of the outing in his diary.

4

19.2

It was no longer the exception but the rule for British subjects to be conscripted into the army or jailed if they refused. By some miracle, Lord Lyons received a letter from a Yorkshire lad in a Southern jail in Mississippi. The writer was desperate for help: “I was, like a very dog, ordered to ‘fall in,’ ” he wrote, “and were sent to this place and placed in artillary [

sic

] companies. I again told my captain of my immunity from the service but it availed nothing.… I was sick from exposure and sent to hospital where I have been ever since, except the last two weeks when I was arrested and sent to Jail, where I now write this, charged with cursing the Confederacy and trying to escape the place, which they term desertion.”

16

TWENTY

The Key Is in the Lock

A great gamble—Death of Stonewall Jackson—Grant reaches Vicksburg—Arthur Fremantle meets the famous Colonel Grenfell—Feilden in love

T

he discovery that Hooker had divided his army and was planning to crush him like a nut between two hammers came as a tremendous shock for Lee, who was unused to being tricked by his Federal opponents. Having weighed the various risks and options for his army, Lee decided that the greatest danger came from Hooker’s advancing forces rather than the 47,000 Federals still remaining at Fredericksburg. Fortunately, Lee had avoided the trap of dispatching part of his army to defend Richmond, having correctly guessed that the Federal cavalry raids around the capital were nothing more than a feint. Even so, Lee could afford to leave only 10,000 men to hold Fredericksburg. The remaining 52,000 he ordered to turn around and take up defensive positions just beyond Chancellorsville. Lee planned to attack Hooker’s troops as they emerged from the Wilderness, using the advantage of surprise.

The fighting began on May 1, 1863. At Fredericksburg, General Sedgwick fired some artillery at the Confederates and engaged in a few skirmishes. It was hardly the aggressive movement envisaged by “Fighting Joe” Hooker, but to the raw and untested second lieutenant Henry George Hore, it seemed as though he had participated in a marvelous triumph. Hore had joined Sedgwick’s staff only a few weeks earlier, having sailed from England to do his part in freeing the slaves. “We are victorious and captured [the Confederates’] batteries, men and all,” Hore wrote in the afternoon to his cousin Olivia; it had been “the Battle of Fredericksburg the Second.”

1

Francis Lawley had rushed from Richmond as soon as he heard that Hooker was on the march but was disappointed that the Wilderness’s impenetrable scrub made it impossible for him to see what was happening. What blinded him also hindered Hooker’s generals as they tried to lead their men through the woods. At 2:00

P.M.,

after meeting relatively light pockets of resistance from the Confederates, Hooker suddenly called off the advance and ordered his army to retreat back to Chancellorsville. His commanders begged him to continue fighting. Hooker was obstinate: “I have got Lee just where I want him,” he told General Darius Couch, who walked away from the meeting convinced that “Fighting Joe” “was a whipped man.” Hooker was never able to explain his decision afterward except to say that all of a sudden he lost faith in himself.

2

That night, Lee and Stonewall Jackson discussed how to take advantage of their adversary’s hesitation. They agreed to divide their already outnumbered army into even smaller segments. Jackson would take thirty thousand men and march around Hooker’s army, relying on local guides to find a way through the Wilderness, and surprise him from the rear, while Lee remained in front with just fifteen thousand troops. In any other battle, the enemy cavalry would have spotted such a maneuver, but Hooker’s was miles away, destroying barns and canals.

When Hooker was informed that large troop movements were taking place, he decided that it meant the Confederates were retreating back to Fredericksburg. It never occurred to him that Lee would attempt an attack from two different directions, using the same divide-and-surprise tactic that he himself had intended to employ. The next day, May 2, at five o’clock, just as the Federals were sitting down to cook their dinners, Stonewall Jackson ordered his men to charge. “Swift and sudden as the falcon sweeping her prey, Jackson had burst on his enemy’s rear and crushed him before resistance could be attempted,” wrote Francis Lawley in a sudden fit of poetry.

3

The rout was so complete that an entire wing of the Union force collapsed and ran back toward headquarters, some two miles away. The first Hooker learned of the battle was when one of his staff officers happened to walk out onto the veranda and look through his field glasses. “My God, here they come!” he shouted.

4

The lines between the two armies became blurred as the twilight turned to darkness.

Hooker was not beaten yet, however. Though strangely passive with regard to his immediate danger, he had no trouble directing the operations at Fredericksburg. Furious that Sedgwick had been poking rather than smashing the Confederates’ positions, Hooker sent him a terse message demanding the capture of the town, and instructed the message bearer to stay until Sedgwick had moved into action.

5

The direct order had its effect.

Henry Hore was up early on May 3, riding hard between Sedgwick’s headquarters and the batteries. Now he saw real fighting instead of the tepid firing of the day before. It was a shock for him to discover that the rebel soldiers handled their rifles with far greater accuracy than his own side. Sedgwick’s troops were flailing until the Federal artillery unleashed its guns. There was such a long delay before the first explosions, wrote Hore, “that I thought [the rebels] would take the guns before we fired. At last came the word: ‘Depress pieces’ and I quite felt sick, they were just about fifty yards or so from my horse who was as much excited as myself.”

The next hour was Hore’s initiation into the sordid truth of war. “Good God, my dear girl, it was awful,” he admitted to his cousin Olivia. “Their dead seemed piled heaps upon heaps, the shot went right clear through them, completely smashing the front of the columns.” Sedgwick ordered ten regiments to charge across the plain toward Marye’s Heights, the same attack formation that had decimated the Irish 69th and so many other regiments in December. But this time there was only a thin line of Confederates behind the famous stone wall, and in half an hour the attackers were up and over, lunging forward with their bayonets. Sedgwick was so excited that he tore a page from a letter meant for his wife and scribbled an order for more artillery. He gave it to Hore with the command to ride as fast as he could and return with every gun he could find. A fellow officer named Hansard, who had abjured his home state of South Carolina to support the North, offered to accompany him.

The two officers were almost at the rear when a Confederate raiding party came crashing through the trees with terrifying whoops and yells.

6

Hore wheeled his horse around, hoping that Hansard was with him. But when he looked behind him he saw one of the raiders spur his horse on and reach out to grab Hansard’s bridle. Hore made a split-second decision to turn around. As he did so, the two riders struggled and fell to the ground. Hansard landed on his back. While he lay helpless, a Confederate cavalryman whipped out his sword and plunged it into his chest. Hore watched, aghast, as the raider leaned forward and tore off Hansard’s shoulder straps. The rebel locked eyes with Hore and shook the straps at him. “I now felt as if he or I must be killed,” wrote Hore. Time slowed and each movement became exaggeratedly clear in his memory. He pulled out his revolver and galloped toward the cavalryman: “I had made up my mind I would kill him if I could.” The rebel either had no gun or forgot he had one. When Hore was sure he would not miss, he fired straight at him: “This did not take 30 seconds,” he wrote, “not near so long as it takes me to write. I sighted him along the barrel of my revolver and if I had not killed him the first time would have shot again, for H[ansard] was a good friend to me.”

7

Map.14

Chancellorsville, May 2–6, 1863

Click

here

to view a larger image.

Hore remembered little else of that day. Once the Federal army had breached Marye’s Heights, the Confederates pulled back toward Chancellorsville, making a new stand in the woods around Salem Church. Though still outnumbered, the Confederates managed to hold down Sedgwick’s troops. Hore was confused and thought that the Confederate retreat meant another victory. “They have not gained (the Rebels I mean) a single yard,” he wrote, “and we don’t mean they shall,” not realizing that in Hooker’s plan, Sedgwick should have been at Chancellorsville by now, helping to smash Lee’s little army. By this time, Hooker was sorely in need of Sedgwick. Shortly after nine o’clock on the morning of the third, a Confederate cannonball had smashed into the veranda of Chancellor House, knocking Hooker unconscious. Though still groggy after coming to, he insisted on resuming command, much to the dismay of his staff. Contrary to his commanders’ wishes, Hooker ordered a general retreat.

Shortly after Hooker’s departure, Chancellor House went up in flames.

20.1

Lee trotted up to the burning house as Confederates came running toward him, cheering and shouting wildly. Behind them the Wilderness had been transformed into a roaring furnace, trapping the lost and wounded. Men closest to the conflagration could see figures waving in the inferno. Union and Confederate soldiers braved the searing heat to pull out anyone they could. Two enemies fought together to rescue a trapped youth: “The fire was all around him,” recalled the Federal soldier. They could see his face: “His eyes were big and blue, and his hair like raw silk surrounded by a wreath of fire.” In vain, they burned their hands trying to reach him. “I heard him scream, ‘Oh Mother, O God.’ It left me trembling all over, like a leaf.” The defeated rescuers fled the forest. Although it was agony to open their fingers, “me and them rebs tried to shake hands.”

8